![]()

PART ONE

STRONG FOUNDATIONS

![]()

1

USING INTUITION, ANECDOTE, AND OBSERVATION

Rich Sources of SoTL Projects

Gary Poole

What if inside every teacher was a scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) project waiting to be brought to life? I believe this is a real possibility because the act of teaching is so cerebral, so academic, and so social that it is impossible to engage in it without developing an internal system of beliefs about what is or isn’t going on. In this chapter, I take a closer look at how these beliefs can become curiosities and how these in turn become the origins of SoTL projects. In doing so, we need to explore some of the sources of our beliefs about teaching and learning. I look at three main sources: our intuitions, our anecdotal experiences, and our direct observations.

Intuition, anecdotes, and observation live close to home for us in our thinking, our interactions with others, and our direct experience. This personal relevance yields a rich collection of beliefs that can pertain to anything and everything related to teaching and learning, from how people learn to what constitutes effective teaching in a particular context. At the same time, these beliefs can vary considerably in their veracity. It is this compelling combination of important richness and varying accuracy that makes for great starting points for SoTL work.

One way to think about this is to problematize our thinking, using the word problem as Bass (1999) uses it. Problems are not negative things; rather, they are interesting challenges for the scientist and humanist within us. Although this might help us understand the source of many SoTL projects, we should not fall into the trap of believing that all SoTL projects must solve a problem. Some will provide elegantly insightful descriptions of a learning process or environment.

Regehr (2010) presented a clear contrast between research intended to solve something as opposed to research intended to explore something.

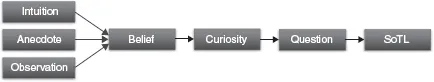

From Beliefs to Curiosities

For our rich beliefs to become motivators of SoTL projects, they must first be transformed into curiosities. This happens using general questions such as, Is this belief about teaching and learning really true? or What are the implications of this belief ? It is when we become curious about our beliefs that we are motivated to examine them through research. Thus, sources of our beliefs, such as intuition, anecdote, and observation, can become sources of our curiosity, which in turn become the origins of SoTL projects. This process is presented in Figure 1.1.

Because they are fundamental to an understanding of the ways many SoTL projects find life, our exploration is organized around the three starting elements in the flow chart: intuition, anecdote, and observation.

Intuition as a Source of SoTL Project Ideas

Intuition (n.d.) is defined as “any quick insight, recognized immediately without a reasoning process.” Similarly, Benner and Tanner (1987) define intuition as “judgment without rationale” (p. 23). These definitions are consistent with Daniel Kahneman’s (2011) notion of System 1 thinking.

According to Kahneman (2011), much of our thinking takes place at a rapid pace, relying on assumptions and intuitions that are quickly accessed from memory. He contrasts this high-speed System 1 thinking with System 2 thinking, which is much more plodding and deliberate. When we engage in System 2 thinking, we take the time to question those assumptions and intuitions. We collect more information, and we reflect more on it. In essence, SoTL projects that find their origin in our intuition represent our way of moving from System 1 to System 2 thinking about our teaching and students’ learning.

Figure 1.1. How SoTL projects flow from intuition, anecdote, and observation.

Kahneman (2011) helps us see how SoTL projects may find their origin in our intuition but then move from fast thinking to slow deliberate thinking about our teaching and our students’ learning.

It isn’t easy to reflect on intuition, however. We must expose what is often unexamined and automatic. Marano (2004) underscores the inherent paradox in this process when she observes, “The act of reflecting on intuition is precisely what intuition isn’t” (para. 5). Furthermore, intuition can yield such deeply engrained beliefs that we simply aren’t curious about these beliefs; rather, we see them as self-evident truths. Thus, there hardly seems to be any point in mounting a SoTL project to test what is intuitive.

But it is exactly this way of thinking—that intuition is self-evident—that makes it a vital and necessary source of SoTL projects. In teaching and learning, we must systematically examine what we take to be obvious because it so often turns out to be anything but. See Table 1.1 for some examples of beliefs we might hold intuitively, and for which research might tell a different story.

TABLE 1.1

Some Intuitive Beliefs That Might Not Be Supported by Research

The Belief | The Research |

Today’s students prefer to learn in groups or teams. | Students might not prefer group work because they sometimes feel they are expected to deal with complex social dynamics in group work without much support from instructors (Hillyard, Gillespie, & Littig, 2010). |

Today’s students are skilled multitaskers because they are frequently juggling information from a range of devices and sources. | In a study of American and European students, the tendency to multitask was negatively associated with academic performance. The effect was most pronounced in the American sample (Karpinski et al., 2013). |

Learning styles are tantamount to stable traits that do not change over time. | Although some approaches to learning carry over from one situation to the next, it would be more accurate to think of learning styles as approaches to a learning task that are, at the very least, dependent on the nature of the task (Cassidy, 2010; Loo, 1997). They are not the same as personality traits. |

There is a large amount of literature on the fallibility of intuition (Chabris & Simons, 2010). Yet it would be a serious mistake to dismiss intuition out of hand, especially when it comes from experienced practitioners. Indeed, effective System 1 thinking is a defining characteristic of expertise. At the same time, it is also a source of things like medical error (Croskerry, 2009). Again, these two possibilities—intuition as fallible yet also the stuff of expert thinking—make intuition so fascinating and important as a source of SoTL project work.

For example, our intuitions about how people learn may well be born from an understanding of how we learn. If we believe our learning flourishes in collaborative settings, then we might conclude that all people learn best by collaboration. There will be times when this intuition is correct and others when it is not, and this is where a SoTL project waits to be brought to life.

Anecdotes and the Power of Conversations

We are beginning to develop a better understanding of how informal conversations with colleagues affect our understanding of teaching and learning.

Roxå and Mårtensson’s (2009) work illuminates why anecdotal data are so powerful: Our conversations, which are often rich in narrative, are particularly memorable.

Roxå and Mårtensson’s (2009) identification of what they call “small significant networks” (p. 547) indicates that our beliefs about teaching and learning are shaped in part when we express ideas to others and they express their ideas to us. Our conversations within these networks are an important source of anecdotal data because these conversations are often rich in narrative, making them particularly memorable compared to, for example, a paper we read. When a colleague says, “You won’t believe what happened in my second-year class today,” we are hooked.

It has been suggested that we select our network members astutely with a preference for those we believe share similar views and may have had similar experiences (Poole, Verwoord, & Iqbal, 2017). Although this selection strategy might be comforting and reaffirming, it runs the risk of ensuring that we confirm rather than examine our views about teaching and learning and that we do so with what appears to be trusted data that are rarely questioned. However, just as intuition may vary between being fallible and insightful, so too can the anecdotes we share in our conversations in networks. Anecdotal evidence, just like intuition, becomes an excellent source of ideas for SoTL projects. This requires us to hear the conversational contributions of colleagues not as statements of truth but as hypotheses.

We’ve all had conversations with a colleague who talks about “students these days.” (See Poole et al. [2017] for a description of ways we might talk about this.) How did that conversation go? Did it start with, “I have some hypotheses about student motivation based on my experiences in the classroom. It would be good to test those”? Or did it start more simply with, “Students these days are so entitled and consumer-oriented that they can be very hard to teach”? If we start with the latter statement, the conversation is more likely to provide opportunities to vent one’s emotions than originate a SoTL project. Significant networks are good venues for venting, and such venting might at times be a healthy thing to do. However, it rarely moves us forward in our pursuit of excellence in teaching and learning. As suggested in the first statement, there may be reasons to suspect that some students exhibit a high sense of entitlement. Testing this is warranted and necessary and would make a very good SoTL project. We need to turn our beliefs about students into curiosities because these beliefs, especially when based on emotionally charged conversations with others, might be less than accurate.

Of course we know that anecdotes are not truths in themselves. They do, however, have the power of truth, referred to as narrative truth (Spence, 1982). A good story told well is not just attention-getting and memorable. It usually feels true. This is especially the case if it is told by a trusted colleague. As Weinbaum (1999) states in her juxtaposition of narrative truth and fact, we may well “forge a truth that is better held together by the force of narrative rhetoric and metaphor than by fact” (p. 1). This is one reason anecdotal evidence is a valuable place to begin a SoTL project—in this case about the characteristics of students in a particular context.

Observation: What You See Is What You Question

Just as becoming curious about our gut-level or anecdotal beliefs about teaching and learning (rather than simply accepting them) motivates us to take those SoTL projects from within us and bring them to life, so too do our curiosities about what we observe. It would seem, though, that the things we observe firsthand are least likely to be subject to bias and, therefore, do not need to be tested by a SoTL project. For example, we see with our own eyes that those students who choose to sit at the back of a lecture hall are less engaged than students who sit toward the front. As another example, we encounter students who come to our office to complain about a grade on an assignment, and that complaint seems to lack substance. These things happen, and we see them clearly.

However, with every observation there are at least three important questions we should ask. First, How prevalent is this thing that I have just observed? Second, If it really has happened frequently, how should I best respond? And third, Is there something about me that causes me to observe things this way when others would not? In other words, does this observation illuminate more about me or the situation being observed? How might this observation have been filtered through my own particular assumptions and visions of the world? This final question might be a bit more difficult to answer. It calls for a kind of SoTL project featuring considerable introspection and reflection requiring a level of objectivity that can be hard to summon on one’s own. Still, it can yield excellent and publishable work.

Ascertaining the real frequency of a phenomenon requires more systematic observation than we normally have the time or inclination for in our day-to-day lives. Given such constraints, we suppress our curiosity about the belief. Those students sitting at the back of the room who appear disengaged don’t tend to be the ones we approach before or after class, even for an informal conversation to get a sense of their engagement. In contrast, imagine a project in which we used measures of engagement and mapped students’ engagement scores according to where they sat in the room. If we were to do this for a number of classes, we would develop some measure of how frequently disengaged students sit in the back. We might also conduct interviews with students to ...