![]()

1

OVERVIEW OF THE GRADUATE AND PROFESSIONAL STUDENT TEACHING COMPETENCIES FRAMEWORK

Joanna Gilmore

The graduate student instructor (GSI) program at the University of Texas at Austin’s (UT Austin) Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) emerged in the 1990s. The focuses of the program were to help GSIs teach, improve their teaching, and prepare for their instructional roles as faculty if their goal is to join the professoriate. Although the GSI program’s work was guided by this larger mission, program staff had never formally articulated the competencies graduate students should develop to be effective GSIs or what they would need to know or be able to do to secure jobs as faculty. Thus, we were left to ask questions such as the following:

• How do we know who is an effective GSI?

• What should be the focus of the workshops or the new seminar we are creating for GSIs?

• How do the workshops we offer for graduate students fit together to inform their development more holistically?

To answer these questions, we needed to develop a GSI competencies framework. In order to begin the process of identifying important GSI teaching competencies, UT Austin’s GSI program coordinator reached out to a diverse group of higher education leaders whose primary responsibility is to promote GSI development. Known as the Graduate Teaching Competencies Consortium (“Consortium”), this group initially included nine members primarily from research-intensive universities in the United States. The GSI program coordinator had been involved with the work of many members of this group as they published a special edition of Studies in Professional and Graduate Student Development (Kalish & Robinson, 2011). She recognized that collaborating with this group around that current work, rather than working individually, would produce a framework that would be more comprehensive and systematically developed and thus, more credible. The GSI program coordinator also recognized that this framework would be useful to other institutions that train GSIs. The result of the conversations and work that followed is published in this book.

Chapter Purpose

This chapter provides an overview of the Consortium’s work from 2010 through 2019. This includes a description of why a teaching competency framework is needed for GSIs, how we developed the framework, an overview of the framework we created, how we intend for the framework to be used, and deliberations we made in developing the framework. Finally, this chapter identifies the structure and purpose of each additional chapter in this book.

The Value of Promoting GSI Development

As early researchers recognized (Chism & Warner, 1987; Davis et al., 2002; Lewis, 1993; Nyquist et al., 1991), graduate students are critical in the higher education academic pipeline. To illustrate, historically graduate students teach between 25% and 50% of courses offered at the undergraduate level nationally (Nicklow et al., 2007). Graduate student teaching is also critical because during early teaching experiences teachers establish a teaching style and set of teaching skills (Boice, 1996) that will endure as graduate students enter the professoriate. Although teaching represents only one of the many duties of faculty of higher education, faculty identify this as an area in which they need more professional development (Theall et al., 2010). As Golde and Walker (2006) discussed, “Many new faculty members do not feel ready to carry out the range of roles asked of them, particularly those related to teaching” (p. 5). Thus, impacting graduate student development is a potential doorway for changing faculty practices and promoting institutional change. Partly prompted by the Preparing Future Faculty program (www.preparingfaculty.org), many institutions of higher education (e.g., M.S. Palmer & Little, 2013) have recognized the importance of GSIs and have begun to provide programs focused on their development as future members of the professoriate. That said, the pedagogical competencies that such programs seek to develop are not widely agreed on.

Need for a GSI Teaching Competency Framework

Developing an effective curriculum is critical in delivering high-quality learning experiences (e.g., Barnett & Coate, 2005; Russell, 1997) and may be one of the most important matters in higher education (Hyun, 2006). A solid curriculum provides the basis for instructional design, allowing teachers, instructional designers, and program developers to first consider the purpose of instruction and then backward design the learning activities to achieve desired learning outcomes (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

The goal of the project reported in this book was to clarify the intended curriculum that could guide pedagogical training and support programs for graduate students, particularly the competencies they would need to teach effectively if they join the professoriate. The intended curriculum is one of the three kinds of curricula defined by Moercke and Eika (2002). They suggested that all curricula actually consist of three curricula: (a) the intended (as defined by experts in the field); (b) the enacted (the content and activities actually presented during the training/educational period); and (c) the achieved curriculum (the knowledge and skills that participants can demonstrate after instruction). To address the growing concern (e.g., Golde & Walker, 2006; Krebs, 2014) that graduate school only prepares students for the ivory tower and does not teach them what they need to succeed on the nonacademic job market, Thomas and Border (2011) built on Moercke and Eika’s work. They added a fourth type of curricula, the desired curriculum, which describes what future employers want new hires to be able to do when they arrive on the job. Although the intended curriculum is critical in designing professional development for GSIs and guided the initial goal of this project, the Consortium also recognizes the need to investigate the enacted, achieved, and desired curricula in the future.

Although some work has been done to identify the competencies that GSIs need (Austin & McDaniels, 2006; Chickering & Gamson, 1987; Fitzsimmons & Fenwick, 1997; McDaniels, 2010; Nyquist & Wulff, 1996; Poock, 2001; Simpson & Smith, 1995; Tigelaar et al., 2004), the existing frameworks are limited. For example, Austin and McDaniels (2006) identified 15 skills and abilities that graduate students need to be successful as faculty. Although this is an excellent starting place for our work, this model is not specific to teaching competencies. Simpson and Smith (1995) identified 26 teaching competencies in six skill areas that are beneficial to undergraduate student instruction provided by GSIs. In both Austin and McDaniel’s (2006) and Simpson and Smith’s (1995) frameworks, the competencies themselves are not fully described. A more complete description would include a definition of each competency, instructional behaviors and strategies associated with each competency, and research that connects each competency to specific student outcomes, as well as information about how to develop each competency. Thus, while we acknowledge that many of the competencies we included in this framework are not novel, what we see as our primary contribution is that we have integrated them into a holistic framework and described each in substantial detail, particularly in terms of how they apply to GSI teaching and professional development.

The framework we propose is necessary for practical reasons. As Austin and McDaniels (2006) and McDaniels (2010) note, currently graduate education is not generally systematically or developmentally organized. This often results in graduate students reporting that they receive “mixed messages” about how they can be successful (Austin & McDaniels, 2006, p. 432), inadequate mentoring (McDaniels, 2010), and limited opportunities for “guided reflection” (McDaniels, 2010, p. 32). Further, when graduate students receive explicit pedagogical professional development, they often report that it does not meet their needs (Golde & Dore, 2004; Gray & Buerkel-Rothfuss, 1991; Luft et al., 2004). Receipt of “mixed messages” and lack of awareness of the needs of GSIs may partly account for the large percentage (roughly 40%) of graduate students who do not complete their programs of study (Golde, 2005). We feel that if administrators, supervising faculty, and graduate and professional student developers were provided with a research-based framework for promoting GSI development, they could better organize systematic professional development opportunities that align with GSIs’ needs. This work may be particularly timely given the expansion of certificate programs for college teaching offered to GSIs (Kalish et al., 2009). Next, I will present the framework we have developed and how we intend for it to be used and then discuss substantial considerations that arose during the development process.

The Graduate and Professional Student Teaching Competencies Framework

The Consortium defines a teaching competency as a convergence of knowledge, behaviors/skills, and attitudes/values/dispositions that support effective instructional practices to promote student learning, professional problemsolving, and instructional decision-making (Biesta, 2009; Le Deist & Winterton, 2007). A competency is larger than an objective (which is usually specific, measurable, and taught in the course of a single workshop or lesson; see chapter 6 for further discussion of the definition of an objective). For example, Competency 5 in our framework focuses on gaining knowledge about how people learn (as well as applying this to instruction). It is not possible to gain this knowledge in the course of a single workshop or class session because there are many areas of research and theories of human learning that are important to consider in instructional design. Thus, gaining knowledge about how people learn is best accomplished through a series of class sessions, workshops, or courses.

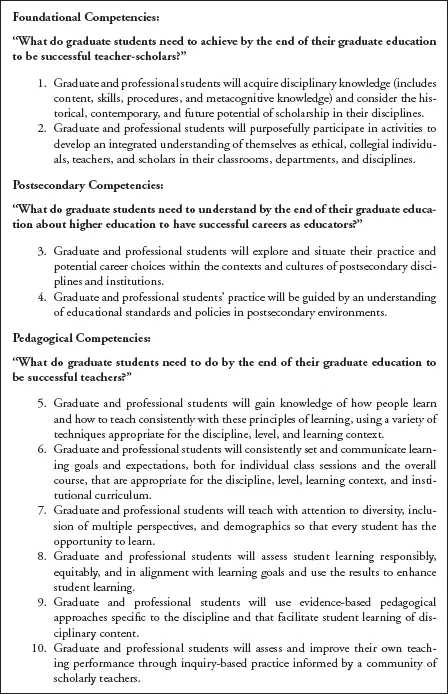

The graduate and professional student teaching competencies framework includes 10 competencies organized around three overarching questions (see Figure 1.1). The first overarching question is “What do graduate students need to achieve by the end of their graduate education to be successful teacher-scholars?” We describe this set of competencies as “foundational competencies” to mean that these competencies are not specific to teaching. In fact, they underlie the graduate students’ development as researchers as well. Although they are not specific to teaching, these competencies are critical for GSIs to become effective higher education instructors. For example, it is critical that effective higher education instructors have an in-depth and organized knowledge of their discipline in order to be able to teach novices. Chapters 2 and 3 focus on the foundational competencies and explain how these competencies connect to teaching effectiveness.

The second overarching question that our framework answers is “What do graduate students need to understand about higher education to have successful careers as educators?” The “postsecondary competencies” focus on what GSIs need to know about the larger environment in which they will teach in order to become effective higher education instructors. Though not directly related to pedagogy, these competencies indirectly influence GSIs’ classroom practices and should not be ignored. The emphasis on graduate students learning about their institution is also supported by other researchers (Austin & McDaniels, 2006; Gaff et al., 2003; Pruitt-Logan et al., 2002). Chapters 4 and 5 focus on the postsecondary competencies, describing the contexts, cultures, policies, and standards in higher education that should inform GSIs’ teaching practices.

The third overarching question that our framework answers is where our discussions began. It addresses the heart of this work: “What do graduate students need to do by the end of their graduate education to be successful teachers?” To address this question, we have identified six “pedagogical competencies” that GSIs need to be effective instructors. Chapters 6 through 11 describe each of these competencies in detail.

Figure 1.1. Graduate and professional student teaching competencies framework.

Competency Development Process

To develop the competencies framework discussed in the last section, the Consortium first met in April 2011 in Chicago for a 2-day meeting and continued to meet in person once or twice per year. These meetings were typically held the days before the Professional and Organizational Development (POD) conference, which most of the Consortium members attend. The Consortium members also met via Web conferences.

At the first meeting in 2011, the Consortium members clarified the purpose and goals of the Consortium and began discussing the value and purpose of a set of teaching competencies for GSIs. At this meeting, we also began to brainstorm the competencies that might be included in this model. Thus, the ideas we initially generated stemmed from the members’ knowledge of the literature on teaching effectiveness and experiences working with GSIs. A subsequent meeting in Atlanta in October 2011, as well as several Web conferences, were used to make improvements to the competency statements, generally focused on using terminology that resonated with Consortium members and the constituents they serve. My involvement in a forum on teaching, learning, and research held by the Center for the Integration of Research on Teaching and Learning (CIRTL) the very same month reinforced the value and timeliness of the work we were doing, as one of the purposes of the forum was to develop a “shared vision for futu...