![]()

1

THE SHIFTING LANDSCAPE

As a lapsed political scientist, I have a keen appreciation for the challenges of futurists. After all, a few decades ago we believed the American model of democracy was in the ascendant and poised to spread across the globe. A few years ago we thought increasingly sophisticated quantitative systems would make election outcomes, and their explanations, more predictable. Until recently, the European Union was seen as a lasting, stable solution to that continent’s history of conflict. And these are just the prediction challenges of one discipline.

Today, there is no shortage of predictions, usually dire, about the future of small independent colleges and universities. And there is no shortage of rhetoric challenging the assumptions behind these forecasts. Are small colleges doomed to irrelevance in the face of changing demographics, a broken business model, and the rise of technology? Are the liberal arts an essential and enduring feature of higher education or an outdated luxury for the privileged elite?

This book does not attempt to add to the list of prognostications, nor does it offer a simple solution to the issues facing most independent colleges. Rather, in the midst of the angst and dire predictions about the future of small colleges, it attempts to move through the anxiety and outline ways in which small colleges can adapt, and in some cases are adapting, to a changing environment. The shifts in the landscape are not entirely new, but they have been accelerating in recent years, and understanding the major issues is essential to identifying how small colleges can best respond.

Perhaps, as I once suggested in previous writing, small colleges and universities are more akin to Broadway, that “fabulous invalid” whose demise has been regularly predicted, and yet somehow never realized. Broadway now thrives on a mixture of innovation (Hamilton), reinvention (jukebox musicals), and classic productions (South Pacific, anyone?). As we will see throughout this book, independent colleges and universities are also adopting multiple creative approaches as they seek a path to sustainability.

Small colleges and universities have already been actively responding to the changing environment, with various degrees of success. There is much to be learned from their emerging efforts. This book presents a taxonomy for organizing the approaches small independent colleges and universities are using to respond in order to understand the opportunities and issues inherent in each path.

After outlining the different approaches small colleges are employing to adapt to the shifting landscape, I offer a template for making key decisions about the future of an institution with questions that help contextualize the challenges and opportunities. While the environmental changes are felt across the country, the success of different responses is influenced by location, history, and type of campus. Context matters, and this template provides a means of evaluating the positions of specific campuses.

Finally, I consider the ways in which small colleges and universities are expanding their vision of consortia and partnerships in order to enhance both fiscal and educational sustainability. Regardless of an institution’s position in the taxonomic framework, many campuses are adding to their internal innovations a fresh view of how to effectively link with other campuses or with other external partners.

Fundamental Changes in the Independent College Environment

While there are sometimes conflicting predictions about the fate of independent colleges and universities, there is little debate that the environment for these institutions is changing in ways that can challenge their missions, their institutional stability, and even their viability. These changes are affecting small colleges in much the way climate change is affecting our larger environment: slow (but accelerating), inexorable, and necessitating a fundamental shift in the way we operate. Any successful path forward must address these changing external realities.

A closer look at the shifts that are confronting the business and educational approach of independent colleges helps frame their dilemma. The pressures include four key factors: changing student demographics, a business model that no longer yields reliable growth, significant shifts in market demand for traditional liberal arts programs, and the expanding use of technology.

The first major recent change for small colleges and universities is a significant shift in demographics—in the profile, geographic location, and number—of young people who are of traditional college age. These demographic shifts are at the heart of the challenges facing small colleges, and declining birth rates indicate the problems will only accelerate in the next two decades. From the 1950s through the beginning of this century, college enrollment was fueled both by population growth and by an increase in the percentage of the population seeking college education. That growth has now leveled off or decreased, depending on region of the country (Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 2017).

Along with the flatlining of the traditional college-bound population is a changing student profile. Where there is some growth in the high school population, it is primarily in groups that have been historically underrepresented in higher education. The percentage and number of White students graduating from high school is decreasing, and that decrease is projected to continue. Meanwhile, Hispanic, Black, and Asian Pacific Island high school graduates are increasing gradually in raw numbers and significantly as a percentage of their graduating cohorts. This is a change in more than complexion. Compared to White children, Hispanic and Black children are twice as likely to be from low-income families and half as likely to have a college-educated parent (Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 2017).

This shift in student profile adds urgency to the quest for independent colleges and universities to adapt and remain viable. If higher education has been heralded as the great equalizer, then the increasing proportion of students who are low income, ethnically and racially diverse, or first-generation college challenges our institutions to live up to the promise of higher education as a means of personal opportunity and social change. The pressure for small colleges is particularly pertinent, for on the one hand, the environment of independent colleges makes them particularly well positioned to respond to an increasingly diverse student body; small classes and integrated support systems can be especially effective in promoting student success (Kuh, O’Donnell, & Reed, 2013). They are essential elements in providing the needed support for first-generation and underrepresented students. On the other hand, many small colleges were created for, and still primarily serve, middle- and upper-middle-class White students.

As we will see later in this book, some independent colleges and universities are effectively embracing the changing student population, with encouraging results. Chapters 5 and 6 include profiles of Trinity Washington University, Dominican University of California, and California Lutheran University. Each provides examples of differing, but effective, approaches to serving highly diverse student populations.

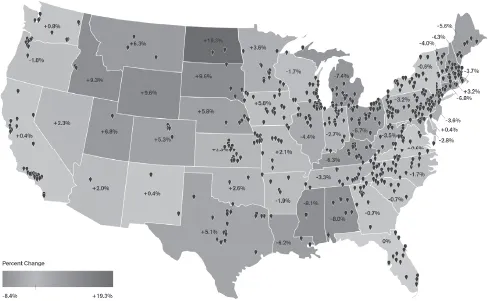

Adding to the challenge of the changing student profile and stagnation in growth of the traditional student population is a geographic challenge. Stated bluntly, independent colleges and universities are not located in areas where the population is growing. The brick-and-mortar locations of these campuses are largely in the Midwest and Northeast, the areas with the biggest decline in the college-going population. Figure 1.1, a simple map that integrates change in the college-age population and the location of members of the Council of Independent Colleges, highlights the misalignment.

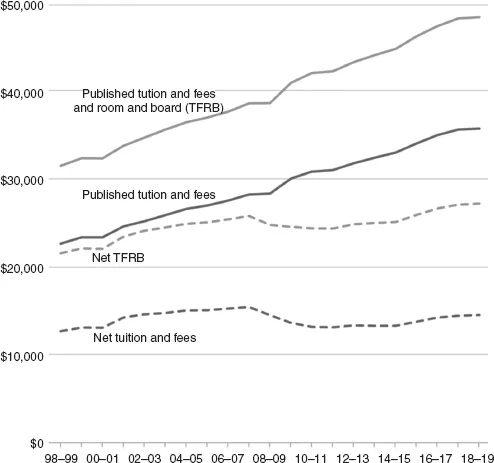

The second major pressure that is facing most small colleges and universities is the failure of—or at least extreme stress on—the business model. Fundamentally, this means that the high-tuition, high-financial-aid approach to student enrollment is not yielding the same results that it did a decade or more ago. As both the sticker price and the tuition discount rate have steadily risen, the bottom line of net tuition revenue has barely shifted for nearly two decades. For tuition-driven institutions—a category that encompasses most small independent colleges—this stagnation has placed tremendous pressure on the business model, as illustrated in Figure 1.2.

The high-tuition, high-financial-aid model has always been dependent on a robust supply of middle- and upper-middle-income families that are able and willing to pay close to the full cost of their education. As the national wealth gap grows, and as more of those students aspiring to college are from lower-income families, there are fewer families in the pipeline with the capacity to pay full freight. In addition, many colleges find that, even if they are able, there are simply not enough families willing to pay the costs of private higher education. Both of these factors have escalated as institutions ratchet up the high-tuition, high-aid model in hopes of gaining some additional revenue. And the problem has also escalated as campuses provide merit aid to bid for students regardless of their ability to pay. Savvy, reasonably financed, and well-coached families do not expect to pay the full cost of private college. Meanwhile, a growing number of students and families are simply unable to do so.

Figure 1.1. Independent colleges and projected change in high school graduates, 2017 to 2023.

Note: Image produced by Margaret Wylie. Data from Council of Independent Colleges (2019) and Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (2017).

Figure 1.2. Average published and net prices in 2018 dollars, full-time undergraduate students at private nonprofit four-year institutions, 1998–1999 to 2018–2019.

Note: Reproduced with permission from the College Board (2018).

Some independent colleges have responded to this reality by implementing a tuition reset process; essentially, the institution decreases the sticker price and simultaneously reduces financial aid, in the hopes of increasing both enrollment and net tuition revenue. This approach is inconsistently successful and demands considerable assessment prior to implementation (Lapovsky, 2019). Ultimately, both the high-tuition, high-aid approach and the reduced sticker price achieved through tuition resets face the same fundamental challenge: There need to be enough students able and willing to pay full, or near-full, price.

This book contains useful examples of emerging strategies to address the cost of college. In chapter 7 there is a description of Utica College’s successful tuition reset process. Chapters 5 and 6 illustrate creative new strategies developed by California Lutheran University and by Dominican University of California to align scholarships to regional needs. And chapter 10 outlines several innovative new approaches to consortia, partnerships, and program delivery that are designed to lower the cost of college and help institutions and students develop alternatives to the high-tuition, high-aid framework.

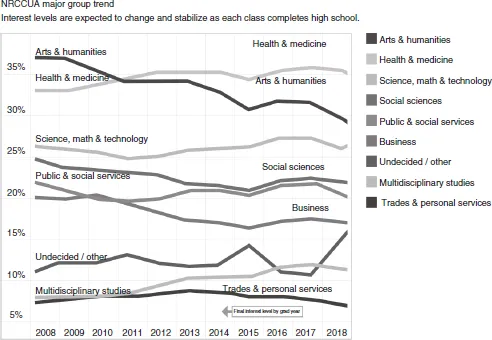

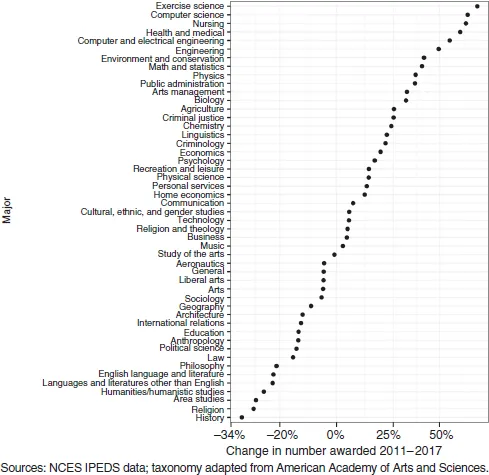

A third major change in the environment for small colleges is a shift in market demand for different disciplines. Historically, attaining a college degree was considered both an individual asset and a social benefit, but there is now a dominant narrative that the primary purpose of higher education is to secure well-compensated employment. One of the most tangible results of viewing college as primarily a pathway to employment is a significant shift in demand toward programs and majors that are clearly aligned with post-graduation careers, as seen in Figure 1.3 and Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.3. Changing student demand for traditional academic programs.

Note: Image courtesy of National Research Center for College & University Admissions, featuring data from WICHE and Encoura Data Lab by ACT (2016).

Figure 1.4. Change in degrees, 2011–2017.

Note: Data from Schmidt (2018).

These data show a move away from the programs typically offered in the liberal arts curriculum and toward more instrumental degrees. The one ray of optimism for small liberal arts colleges in these data is the growth in “undecided,” as students may still be going to college to find their path, rather than simply to fulfill the requirements for employment. Small colleges must either convince prospective students and parents that a liberal arts degree can lead to a good job, or must more consciously show the path to employment post-degree; in addition, many are adding programs that are in high demand and more obviously tied to specific careers.

The emerging models for small colleges and universities outlined in this book illustrate many ways in which these institutions are responding to the changes in demand for different programs and to the expectation that college will lead directly to employment. These responses range from building more systems that link the academic experience to career, to guided pathways to aid in students’ exploration, to actively adding programs that are in high demand by employers. The manner in which institutions are adapting to career expectations represents one of the biggest distinctions among the emerging models of small colleges.

Fourth, the rapid evolution of educational technology and the growth of online courses and programs have put additional pressure on traditional campus-based learning. The full impact of these changes is not yet clear. Certainly the prediction that place-based institutions would be rendered irrelevant by technology has not come to pass. Massive open online courses (MOOCs), in particular, have not replaced campus-based learning. But increasingly sophisticated educational technology has built a new market, especially in professional retraining with nontraditional-age students. In some ways, the fact that educational technology has not replaced in-person learning reinforces the notion that traditional-age students still seek to “go to college” in some familiar manner, one that includes a range of experiences b...