![]()

PART ONE

STARTING

![]()

1

PREPARING FOR YOUR COURSE DESIGN

Points to Ponder

In thinking about designing the courses you teach, consider the following questions to examine your prior knowledge:

• What are your experiences in teaching your courses as a new or midcareer faculty and how does that affect your course design proficiency? What data do you receive about your course’s success? What measures do you use to determine how well the course is working?

• How well are students succeeding? What changes in content or practices will help students be successful in their careers?

• In thinking about your courses, which would you most like to redesign?

As the midsemester exams were graded, Catherine enjoyed a hot mocha at the local coffee shop. She reflected on her classes, students, teaching, and where she was in her career. In her seventh year of teaching full time, having been an adjunct for three years previously, so many things had changed. Catherine thought about what she knew now that she didn’t know when she started.

She taught her first courses as mirror images of the way she was taught at her university. She hadn’t struggled as a student so it was difficult to understand why her students didn’t just get the content. As a student she was able to memorize well; apply the material; and ace the tests, even essay exams. As a graduate assistant, she got high ratings from her professor as she graded assignments and completed the work he passed on to her. She was glad that she provided a bit more feedback to her students now as it seemed to help them perform better.

Catherine was very confident in her current disciplinary knowledge. As a subject matter expert she had attended professional association conferences every other year to be sure she knew what changes were taking place in her discipline so she could modify her course content. Her students were performing fairly well. She referred them to the learning center as needed and worked with her department to offer study sessions. However, she noticed most of her students didn’t take the opportunities for extra help. The course completion and pass rates were on par with her colleagues, matching the department average.

But something was nagging at Catherine. Could she make her courses and teaching any better? She had gone to some campus teaching and learning workshops, picking up some great tips here and there. She had learned about her students. Every time she had a student with a learning challenge she learned a bit more about making accommodations. She knew that some students weren’t college ready. Perhaps they just needed to try harder, but she also wondered what she could do to help them succeed in her courses. She had inherited her courses and had made a few changes over the past five years. However, she still felt a bit trapped to teach like her peers. She had a mix of face-to-face and online courses. Students seemed to like the flexibility of online courses, but she felt a distance in communicating with them that she didn’t feel when she met with her classroom courses. What could she do to bridge that gap?

Catherine knew how she learned but didn’t understand how others learned. She gained some perspective by talking with the students who came in during office hours. What could she do to help students who were not great at the memorization and applying content like she was? She also began to wonder how her courses could be designed to make learning accessible to all her students from the start so she would need to make fewer changes to help them during the semester. Was there new technology that could help her communicate with her students and provide learning in a more significant way so students would benefit in their career long after they left her course?

Catherine gave tests and allowed students to choose projects in some of her courses. Was this enough? She knew students were passing tests but wondered if she was really assessing their mastery of the course outcomes. Hearing about some of her colleagues on campus who were assessing the quality of their courses, she wondered how her courses would compare to theirs. In a couple of years, Catherine’s department is going to reapply for accreditation, and she wanted to be sure her courses would help the department in the evaluation. She was also asked by her dean to sit on a faculty committee to prepare for the institution’s upcoming accreditation.

Catherine’s reflection was giving her some insights. She knew she wanted her courses to significantly affect her students’ learning, prepare them for their careers, and help guide them to successful lives. She opened up a book she got at her campus center for teaching and learning, Designing Effective Teaching and Significant Learning, and began reading.

Planning for Course Design

Designing your courses to deliver effective teaching and significant learning is arguably one of the most effective ways to set students up for success. Our goal in writing this book is to assist you as you consider all the elements of course design and its overall impact on student learning, effective teaching, and institutional mission. Blending your prior knowledge and experiences with the content in this book will help you improve your current practice, making teaching even more enjoyable as you see your students more engaged in their learning. We have seen the impact of well-designed courses. We have worked with faculty worldwide to help them deliver the kinds of courses they have always wanted to teach. More important, in this book we share the stories of how faculty have transformed courses from theory to practice. As faculty developers and leaders in course design, we realize how course design models have expanded over the years. We start with Fink’s (2013) foundation of integrating course design and provide additional design concepts to expand the course blueprint to implement plans for communication, accessibility, technology integration, and the assessment of course design as it fits into the assessment of programs and institutions and how you can use what you learn to meet your professional goals. Let’s start this journey by discussing how you can prepare for designing your courses.

Fink (2013) explains the process of design that goes beyond creating an outline for delivering content. Using Fink’s integrated course design approach, faculty develop an intentional course plan by considering the situational factors, reflecting on their big dream for what they want students to take from the course, developing outcomes and assessments first, and then adding the bridging learning activities. Fink (2005) provided the following steps in designing courses for significant learning: In the initial design phase (Steps 1–5), Designing Courses That Promote Significant Learning, if professors want to create courses in which students have significant learning experiences, they need to design that quality into their courses. How can they do that? By following these basic steps of the instructional design process:

• Step 1. Give careful consideration to a variety of situational factors. Use the backward design process.

• Step 2. Determine learning goals. What do you want students to learn by the end of the course that will still be with them several years later?

• Step 3. Create feedback and assessment procedures. What will the students have to do to demonstrate they have achieved the learning goals?

• Step 4. Develop teaching and learning activities. What would have to happen during the course for students to do well on the feedback and assessment activities?

• Step 5. Think of create ways to involve students that will support your more expansive learning goals.

Check to ensure that the key components (Steps 1–4) are all consistent and support each other in integrated course design (Fink, 2005). This abbreviated list of steps is a valuable resource for you in designing your course. See Appendix A for the complete document, where you will find descriptions for each of Fink’s (2005) elements for course design. Chapter 2 will provide the opportunity to use this as you examine your own courses.

Bloom’s and Fink’s Taxonomies

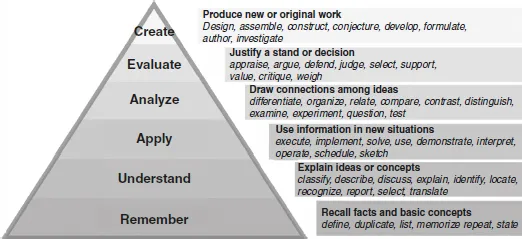

Many of you are familiar with the six levels of Bloom and colleagues’ (1956) taxonomy: Remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating. Many instructors incorporate a variety of these levels in their courses as they scaffold content and experiences to engage students in learning. It is best to use level-appropriate verbs to match where your course lies in the curriculum pathway. Anderson and Krathwohl’s (2001) revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy names six distinct levels of skills (as shown in Figure 1.1):

1. Remembering: recalling information; remembering facts, vocabulary terms, and basic concepts

2. Understanding: demonstrating the understanding of facts through comparison, organizing, providing descriptions or main ideas

3. Applying: using acquired knowledge to solve problems and navigate new situations

4. Analyzing: breaking down information into components, discovering the relationships between parts, cause and effect, identifying inferences and supporting evidence

5. Evaluating: judging the quality of information, ideas, or work based on criteria

6. Creating: putting together parts into a whole; developing models; synthesizing new processes, ideas, or products

If you were teaching the beginning course in a series of courses, you would tend to use more of the lower level outcomes to start and transition to using the higher level outcomes that are appropriate for the advanced skill levels you would like students to achieve as the course progresses. If your course is one of the final courses in curriculum, you would focus on the higher level skills knowing that students had mastered the lower level content in the foundation courses. Higher level course outcomes would be less about understanding at the knowledge or comprehension level and more about analysis, evaluation, or creation. It is possible to use all of the levels in the same course, but unless students will demonstrate new understanding in an advanced course, your outcomes will use verbs appropriate to the comprehensive and application levels and then move to the analysis and evaluation levels.

Figure 1.1 Bloom’s taxonomy.

Note. Bloom’s taxonomy includes the hierarchical domains of remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create. From “A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview,” by D.R...