![]()

1

THE CASE FOR DESIGN THINKING IN HIGHER EDUCATION AND STUDENT AFFAIRS

Poor graduation rates are a topic on most college campuses. Senior administrators understand the importance of retention and graduation rates because graduation rates mean more money through revenue generation and possibly increased state funding, which can fund priorities across the institution including faculty research, student scholarships, and staffing for student support services. While campus resources are important, there are broader implications of college degree attainment for students. Individuals with a college degree have higher earnings than those who do not (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020). They also have better health, housing, and employment benefits (Ma et al., 2016). In addition to individual benefits, there are societal benefits for increased college graduation rates. Higher earnings lead to higher taxes being paid to support public programs (Ma et al., 2016). Individuals with college degrees are less likely to be on public assistance and are healthier, which lowers health-care costs (Ma et al., 2016). Since the establishment of the earliest colleges in the United States, women, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) have been excluded from and minoritized within higher education. Design thinking can be an inclusive process that addresses the complex problems of equity in colleges and universities. While many institutional leaders realize the many benefits for their institutions, their students, and society of improving their graduation rates, they are stuck as to how to go about addressing this problem. Design thinking is a possible approach.

Design thinking is a human-centered approach to innovation that emphasizes building empathy for user needs. Design thinking is a shift away from traditional top-down approaches to product and service design in favor of a more user-centered approach. This chapter introduces design thinking as a creative problem-solving process that emphasizes a focus on building a deeper understanding, or empathy, for the people who will benefit from the design. The argument for the application of design thinking in a student affairs context is one that sets the stage for the deeper examination of design thinking and applications of the process in student affairs throughout the book.

Design thinking has been a staple in the creative world of design, but virtually unknown in higher education and student affairs. As a problem-solving approach, it has the potential to transform higher education by increasing effectiveness through equitable solutions. Design thinking aligns well with student affairs as there are numerous shared values. Design thinking is person-centered just as student affairs is student-centered. Design thinking is a people-based, not technology-based, problem-solving approach that begins with empathizing to gain a deep understanding of the needs of users. The process is inclusive and collaborative, like action research where participants are involved in developing a solution to a problem or issue that directly affects them. As such, there is a focus on equity because the goal is to find solutions for all users—solutions for those on the outer tips of the bell curve, not just for the majority in the center of the curve. Because the approach is inclusive, collaborative, and people-centered, the process is as important as the solution.

Design thinking’s focus on process mirrors student affairs work. Student affairs professionals either directly or indirectly strive to foster student learning and development, which is a process. These staff are not building widgets. The product for student affairs is not students, but their learning and development.

Design thinking also considers culture and context. Neither individuals nor problems exist in vacuums. Elements of culture, such as values, beliefs, assumptions, symbols, and language all affect the way a problem manifests as well as the way a problem or issue may be addressed. These cultural elements need to be made explicit in the emphasizing phase and attended to in the ideation, prototyping, and testing phases of design thinking. A cultural approach to problem-solving is applicable to student affairs because offices, departments, and programs exist in organizations that have multiple layers of culture.

Design thinking is also a process that reduces risk. The purpose of prototyping is to test out solutions before scaling them up for the larger population. The design thinking approach is beneficial in a higher education setting where resources are scarce. In an environment with limited resources, it is better to test out a minimal viable product than go to scale and then realize that there is a problem in the product, program, or service that could have easily been addressed during a prototype phase. Willingness to fail and abandon a tested program or service in favor of something that will be more desirable, feasible, and viable is an important mindset in design thinking. Given the underlying values of design thinking and the characteristics of the process, it fits well with student affairs and higher education.

Finally, design thinking offers rich learning and collaboration opportunities for students. Across institutions there are thousands of talented students seeking meaningful applied learning opportunities. Learning the design thinking process and having the opportunity to work with other students, staff, and faculty on a collaborative and interdisciplinary team is a powerful experience. The opportunities to bring diverse stakeholders into a design process align with the collaborative and consultative cultures at many institutions of higher education. These features of the process are also in alignment with the commitment and value that most institutions place on developing rich learning experiences for students.

At the University of Toronto Innovation Hub, teams of interdisciplinary students work together on projects that impact them in a consulting model, partnering with divisions and departments on campus who want to better understand stakeholder needs and innovate. This ranges from space redesign projects to new programs and services or investments in other innovations. Each student brings their unique experiences and theoretical lens from their area of study to the process, which helps them see their academic knowledge through a new lens. They also have the opportunity to see the importance of context when learning about the complexity of the issues through the eyes of stakeholders who have divergent opinions and viewpoints. Bringing students into a design team offers them practical skills which help them better understand who they are, how they work in a team context, and why complex problems are so challenging to solve.

What Is Design Thinking?

Design thinking is a creative, inclusive problem-solving process that emphasizes a focus on the people who are the beneficiaries of the design. With an emphasis on building empathy for end users as part of the information gathering process, design thinking prioritizes the discovery and deeper understanding of human needs to ensure that innovative solutions are desirable to users. While traditional problem-solving approaches tend to focus on quickly identifying the problem to be solved and moving straight to a solution, the design thinking process encourages building empathy and taking more time to define the problem as viewed from the end user perspective before building solutions. Design thinkers at global design firm and innovation company IDEO (2019) suggest that true innovation happens at the intersection of desirability, feasibility, and viability. A solution to any problem is only innovative when it is:

• desirable, or something the beneficiary of the design really wants and that will meet their needs;

• feasible, or something that can really be done given available resources, systems, and other enabling factors; and

• viable, so something that will advance the goals of the organization and where gains from implementing the solution will bring enough value to justify investments of time and resources (Van Tyne, 2016).

The design process, when regarded through the lens of desirability, feasibility, and viability, provides a recipe for steps to be taken to better define complex problems and generate innovative solutions.

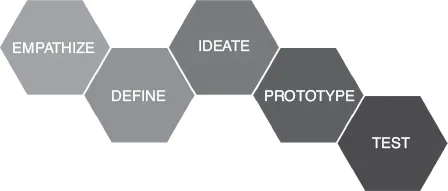

Design thinking consists of five steps: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. First, empathize with users to understand the problem or issue; using what was learned in the empathize phase, define the issue or problem to be addressed through the design thinking process; ideate possible solutions to the problem or issue; prototype solutions which could be a product, program, or service; and test the prototypes making improvements (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Design thinking process.

While the model is often depicted as a linear process, frequently previous steps are revisited. After testing a prototype and learning that it does not address the problem, designers may revisit the ideate step to explore additional potential solutions. A prototype may be tested multiple times after improvements are engineered after each testing phase. Sometimes, designers must go back to the empathize step to further explore the issue to more precisely define the problem. Design thinking is a somewhat cyclical process.

Practitioners may find the steps in design thinking easily understood and intuitive and some may argue that design thinking is common sense. Many practitioners may think they are using design thinking even if they are not following the steps outlined in chapter 3. While easy to understand as a process, design thinking proves more difficult to implement.

There are five key characteristics of design thinking: its use to address wicked problems, use of empathy, a collaborative approach of designing with people rather than for people, design thinking as both a method and mindset, and the emphasis on failure as learning.

Wicked Problems and Design Thinking

It is impossible to discuss design thinking without introducing the concept of a wicked problem. The term has been attributed to planner Horst Rittel (1973) to describe problems that are extremely complex in nature and seem near impossible to solve. Higher education is full of wicked problems. These wicked problems are highly ambiguous, and there are just as many unknown factors as those that are known. There are no clear yes or no solutions to wicked problems. In fact, some of the better solutions often reveal more underlying problems and design challenges.

To add to the complexity of wicked problems, a solution that works today may prove obsolete in the future, and one solution may work only in a certain context but not in others. The information about the problem can be contradictory and confusing, and there are often many decision makers and stakeholders whose values and priorities conflict with one another (Transition Design Seminar, 2020). Wicked problems are nonlinear and complex. Wicked problems require deep inquiry and layers of empathy building prior to solution generation. It is important that the problem is as well-defined as possible before generating solutions to wicked problems. Design thinking helps teams to better define problems.

When thinking about the current state of student affairs in higher education, many examples come to mind. Take, for example, the complexity of student mental health. Campuses and university administrators across the world are struggling to understand and address the issue of mental health. The Higher Ed Today survey of presidents on college student mental health and well-being indicated that over the last 10 years student mental health concerns have escalated, and death by suicide is the number two cause of death for college students (Chessman & Taylor, 2019). This perception is supported by data from the National College Health Association. In spring 2016, 14% of respondents reported being diagnosed for depression (American College Health Association [ACHA], 2016) compared to 22% in spring of 2020 (ACHA, 2020). Student mental health is a complex topic, and there are many complicated factors that come into play. College and university administrators cannot simply think about mental health as a medical issue; they must look at the landscape for today’s students: interpersonal and family relationships, community dynamics, social support, and school conditions (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], 2020).

There is a long list of factors that impact student mental health including the stakeholders who play different roles in the system that supports students during their time in higher education. These factors combine to suggest that mental health is a wicked problem with no simple solution. Addressing this issue requires a quest for deeper understanding of the causal issues at play and building empathy for the various stakeholders to develop an appreciation for the complexity of the issue. Design thinking addresses these types of wicked problems.

Empathy and Design Thinking

Central to design thinking is a fundamental shift in the approach to innovation, problem-solving, and creating that can be summarized in a simple phrase: Design thinking is designing with rather than for people (IDEO U, 2017), highlighting the importance of empathy in the process in a way that makes empathy an action word. As noted earlier, in design thinking, the members of the population impacted by the design process are invited to become active participants in the process. The use of empathy acknowledges that people hold the solutions to their problems and that through engagement with people there can be collective discovery of new solutions that better meet needs. Ultimately, empathy is about understanding the logics, experiences, worldviews, identity, needs, and desires of people. Empathy also requires deep listening and observation as tools to learn about the experiences of others.

A particularly heartwarming example of empathy comes from a project shared with one of the authors with Nogah Kornberg, assistant director of I-Think, a nonprofit initiative making real-world problem-solving core to every classroom. Students are taught design thinking and integrative thinking in K–12 classrooms and given real problems from real organizations where they apply their learning and recommend innovations to the organization. In this example, students at John Polanyi Collegiate Institute in Rahim Essabhai’s class were working on a problem with the community garden at the school, run by a local nonprofit. The issue was that at night people from the community were coming and picking vegetables but were doing so improperly and causing damage to the vegetable plants. Students needed to build empathy for the people who were damaging these plants in order to find an appropriate solution.

Students chose to attend a Toronto Community Housing meeting to understand the issues that residents of the community faced. During the meeting that the students attended, there was a focus on the experience of seniors being isolated, especially in the winter. Senior members of the community shared their experiences at the meeting. The issue of isolation with seniors was particularly concerning, especially in a community where the residents had a great deal of respect for their elders.

After attending the Toronto Community Housing meeting, the students decided that the learning they had experienced about seniors would be important as they developed their solution. The problem the students initially set out to solve was the issue of the vegetable picking at night causing damage to the plants, yet the students felt deep empathy for the seniors in the community. Compelled to address the issue of isolation that these seniors faced, the students used this information to form their solution. They decided that if the garden was rebranded as a garden for seniors, where they could come and socialize while caring for the plans, it would generate enough respect that the community members would learn how to properly interact with the plants to maintain the health of the garden. By engaging in empathy building as a part of their design thinking experience, students were able to create recommendations for the community garden that reflected the culture of the community.

Each individual brings their own mental models, a lens through which they view the world, into the design thinking process. Daniel Kahneman’s work provides useful research that helps give additional insight into how mental models work. In his book Thinking Fast and Slow, Kahneman (2011) suggested that there are two modes of thinking that the brain is capable of. Over decades of research, Kahneman has shown that there is a dichotomy between System 1 thinking, which is fast, emotional, and based on instinct and System 2 thinking, a more deliberate and slower, logical thought process.

In day-to-day life, including life within the workplace, System 1 thinking is commonplace: thinking that is automatic and repetitive, often unconscious. Driving on a highway, addressing emails with the same type of greeting, making quick decisions based on reasoning, and making small talk all rely on some form of automatic thinking that comes naturally and requires minimal mental exertion. System 1 thinking is beneficial as it helps with day-to-day functioning by automatizing what can be automatic and helping our brain make pathways to understanding the world. To do problem definition well, one must enter into System 2 thinking, which is a slower, more methodical, and effortful process, such as when we solve complex mathematical equations, dig into our memory to recognize a familiar yet unknown sound or scent, or try to listen to what someone is saying in a loud environment (Kahneman, 2011).

When carrying out design thinking processes, an equity-centered approach allows design teams to practice examining their own implicit and explicit biases and bring an awareness of these to the foreground. For this reason, the second feature of design thinking is that it encourages intentionality in selecting an appropriate team and requires the right people to be brought into the process.

Designing With Rather than for People

One o...