eBook - ePub

The Craft of Community-Engaged Teaching and Learning

A Guide for Faculty Development

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Craft of Community-Engaged Teaching and Learning

A Guide for Faculty Development

About this book

Using a conversational voice, the authors provide a foundation as well as a blueprint and tools to craft a community-engaged course. Based on extensive research, the book provides a scope and sequence of information and skills ranging from an introduction to community engagement, to designing, implementing, and assessing a course, to advancing the craft to prepare for promotion and tenure as well as how to become a citizen-scholar and reflective practitioner. An interactive workbook that can be downloaded from Campus Compact accompanies this tool kit with interactive activities that are interspersed throughout the chapters. Thebook and workbook can be used by individual readers or with a learningcommunity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Craft of Community-Engaged Teaching and Learning by Marshall Welch,Star Plaxton-Moore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Educación superior. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PedagogíaSubtopic

Educación superiorPART ONE

LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS

Chapter 1

BEING AN ENGAGED SCHOLAR AND DOING ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP

We begin by reflecting on the words of Ernest Boyer (1997), who many consider to be the consummate voice of and advocate for community engagement in modern American higher education. In his remarks to the Association of American Colleges in 1988, Boyer argued:

What we urgently need in the academy, then, are scholar-citizens—people who are committed to building an intellectual community, not just in the classroom but in the coffee shop, and committee room as well. And until scholarship in American higher education means not only publishing, but also designing integrated courses, serving on committees, and spending time with students, I am convinced that our efforts to renew the undergraduate experience will simply be time spent tinkering on the edges. (p. 65)

In another speech to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1995, and later published in Selected Speeches: 1979–1995 in 1997, Boyer described his vision of engaged scholarship:

The scholarship of engagement means connecting the rich resources of the university to our most pressing social, civic, and ethical problems, to our children, to our schools, to our teachers, and to our cities—just to name the ones I am personally in touch with most frequently; you could name others. Campuses would be viewed by both students and professors not as isolated islands, but as staging grounds for action. (p. 92)

If you don’t already have one, download a QR scanning app to your smartphone or tablet. Then, swipe your device over the video code in Figure 1.1 to see and hear a brief introduction of the late Ernest Boyer and then refer to Tool Kit 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Ernest Boyer video.

Note. Scan the QR code to access https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-TFN16faN0

Tool Kit 1.1—Refer to Exercise 1.1 in your workbook. Read and respond to the questions regarding Ernest Boyer’s conceptualization of engaged scholarship.

History and Public Purpose of Engaged Teaching and Scholarship

The public purpose of American higher education is, and always has been, to promote a democratic society (Saltmarsh & Hartley, 2011), taking a cyclical trajectory consisting of five phases, which is described in more detail by Welch (2016). The first phase occurred during colonial America when colleges were primarily Protestant institutions with faith-based service at their core to promote the common good and prepare young adults (men) to be meaningful members in a just and democratic society (Harkavy, 2004; Hartley, 2011). Later, in an effort to rebuild the country after the Civil War, the Morrill Act of 1862 created land-grant institutions to advance education, democracy, and agricultural science in rural communities (Harkavy, 2004).

The post–Civil War Reconstruction era also launched the second pragmatic phase, establishing the American research university when the German university model was adopted at John Hopkins University in 1876. Faculty began to focus on a narrow disciplinary specialization that generated greater loyalty to their discipline than to the broader public purpose of higher education (Benson et al., 2017; Benson, Harkavy, & Hartley, 2005). This led to generating an educational product that could be consumed by the government and business.

By the time of the Cold War, conditions stimulated a push toward big science that evolved into the entrepreneurial commodification of education (Benson, Harkavy, & Puckett, 2011). “Research parks” began to sprout on university campuses to generate products leading to patents that would financially sustain the institution. Grants were sponsored by government agencies and corporate entities, influencing the research agenda at universities. Although the resulting products make significant contributions to the economy as a whole, this trend contributed to a shift away from civic scholarship and the public mission of higher education. Meanwhile, many college campuses were the epicenter of the social movements and demonstrations related to civil rights, women’s rights, protection of the environment, and the Vietnam War.

A malaise emerged after the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, when much of the country as a whole was simply worn out from the strife experienced through the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement. America shifted its attention to personal interest and gratification, often referred to as the “me generation,” when many college students were essentially apolitical. Ironically, from this morass came the first inklings of a civic resurrection, on the part of students no less, supported by a handful of idealistic faculty and university presidents. This third phase was political, albeit a pragmatic political movement rather than a partisan political movement. By the 1980s, college campuses were scrambling to provide programmatic infrastructure that could support and sustain this new surge of student volunteerism.

The fourth phase, focusing on pedagogical purpose, began when college administrators and faculty took note of this growing trend of students’ extracurricular civic volunteerism to integrate service with learning to arch back toward the original public purpose of higher education. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, professional associations and organizations such as Campus Compact were established as a scholarly scaffold to support this work. Research, publications, and conferences on the pedagogy of service emerged, creating the fifth phase of professionalization, in which the field of community engagement has emerged as its own field with its own research literature and professional organizations. Likewise, a new “community engagement professional” (Dostilio & Perry, 2017, p. 3) has taken on a growing leadership role on campuses to advance community engagement.

As such, it is important to realize and understand that civic and community engagement are really not new to higher education. Yet the public purpose and practice of engagement have largely been lost on many campuses and are not widely known or understood by many administrators or faculty within the academy (see Tool Kit 1.2). Although there has been a historical foundation for the public purpose of higher education, it has reemerged over the past three decades. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching has established an elective Community Engagement Classification that institutions can apply for and receive.

Tool Kit 1.2—Refer to Exercise 1.2 in your workbook. Find your institution’s mission statement. To what extent does it align with Boyer’s concept of engaged teaching and learning and the public purpose of higher education? To what extent does this mission of engagement exist or manifest itself on your campus?

It is important for you from a pedagogical, philosophical, political, and pragmatic perspective to understand and be able to articulate how and why your interest and efforts in engaged teaching and learning align with your institution’s mission. Philosophically, you embody the public purpose of American higher education through this work. Pedagogically, you are playing a role in shaping the minds of young adults and influencing change in the institution and community, as well as disseminating new knowledge to your field. Politically, your engaged scholarship advances social justice as well as confronts the neoliberalization of American higher education. Finally, and pragmatically speaking, as we will discover in more detail later in this chapter, it is imperative that you are able to integrate the academic trilogy as well as justify and articulate how your engaged teaching and scholarship falls within the mission of your institution as you prepare for evaluation and/or promotion and tenure, as discussed in chapter 12. In this way, whenever your engaged work is called into question, you are able to link it to your institution’s foundational mission of engagement as you did in Tool Kit 1.2. But what exactly do we mean when we say “engagement” (see Tool Kit 1.3)?

Tool Kit 1.3—Refer to Exercise 1.3 in your workbook. What does engagement mean or look like to you?

What Do We Mean When We Say “Engagement”?

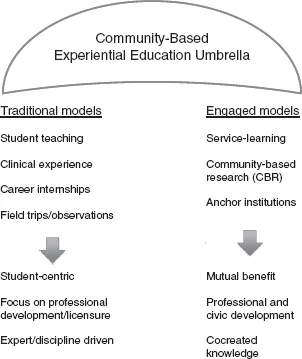

The term engagement conjures up many images. At the same time, many administrators and faculty assume they are using the same lexicon when talking about engagement. There is, however, a broad umbrella of experiential education under which a number of similar but distinct approaches and terms fall (Welch, 2017). In a general and very simplified way, experiential education can be thought of as learning that is experienced outside the traditional classroom in the community. This generic and narrow understanding has resulted in a somewhat careless exchange and use of words as synonyms when, in reality, they represent distinct approaches and purposes. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (2012) defined community engagement as “the collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity.” Votruba (1996) characterized community engagement as academic activities that create, disseminate, apply, and preserve knowledge that serves various stakeholders in a variety of settings. Ehrlich (2000) succinctly described civic engagement as “working to make a difference in the civic life of our communities and developing the combination of knowledge, skills, values, and motivation to make that difference” (p. vi). Each of these characterizations reflects Boyer’s principles presented at the beginning of this chapter. Likewise, although student learning is at the core, engaged teaching and learning transcends an academic focus to include benefit for the community at large. Traditional community-based experiential educational experiences are student-centric, focusing on assimilating discrete academic knowledge and demonstrating mastery of specific skills to earn professional credentials, licensure, or careers (Welch, 2016, 2017). As examined in much more detail in chapter 3, engaged teaching and learning reflect the tenets presented here and differ from traditional forms of experiential education that take place in community settings (see Figure 1.2).

Community engagement, in contrast, reflects the following key components enumerated by the Kellogg Commission (2001): (a) responsiveness to communities; (b) respect for partners; (c) academic neutrality; (d) access to the academy; (e) integration of the academic trilogy; (f) coordination of efforts through a common agenda; and (g) utilization of assets, resources, and partner groups in the community. Likewise, the Committee on Institutional Cooperation (2005) defined engagement as

the partnership of university knowledge and resources with those of the public and private sectors to enrich scholarship, research, and creative activity; enhance curriculum, teaching and learning; prepare educated, engaged citizens; strengthen democratic values and civic responsibility; address critical societal issues; and contribute to the public good. (para. 5)

In essence, community and civic engagement generate new knowledge through the integration of research, teaching, and service that benefits society (Colby, Ehrlich, Beaumont, & Stephens, 2003; Kuh, 2008; Ramaley, 2010). Bringle and Hatcher (2011) summarize that engagement embodies the following characteristics: (a) it must be scholarly; (b) it must integrate teaching, research, and service; (c) it must be reciprocal and mutually beneficial; and (d) it must encompass and reflect civil democracy. In a report to the Ford Foundation, Lawry, Laurison, and Van Antwerpen (2006) note,

Figure 1.2 Community-based experiential education umbrella.

Civic engagement has become the rubric under which faculty, administrators, and students think about, argue about and attempt to implement a variety of visions of higher education in service to society. . . . There is near consensus that an essential part of civic engagement is feeling responsible to be part of something beyond individual interests. (pp. 12–13)

Engaged Scholarship

Engaged scholarship reflects Boyer’s notion of using the rich knowledge and resources of higher education to address social and community needs through research, teaching, and service. Holland (2005) characterized engaged scholarship as the institution and its faculty applying their disciplinary expertise to address public purpose. Similarly, Furco (2005) argued that “engaged scholarship research is done with, rather than for or on a community—an important distinction” (p. 10). Research conducted in this context creates and disseminates knowledge that is beneficial to the discipline as well as the community. He goes on to suggest that the mutual benefit of this approach is that research and scholarship are enhanced and broadened through meaningful input, insight, and involvement by the community. In that light, Simon (2011) proposed that engaged scholarship “continually pushes the boundaries of understanding” (p. 115) through a synergistic interdependence between the institution and community that transcends geographic and socioeconomic boundaries. In this way, community partners bring their own unique public expertise and scholarship to the partnerships as public scholars (Sa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for The Craft of Community-Engaged Teaching and Learning: A Guide for Faculty Development

- Half-title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: Laying the Foundations

- Part Two: Drawing the Blueprint and Using the Tools

- Part Three: Advancing the Craft

- References

- About the Authors

- Index

- Also available from Stylus

- Backcover