- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Navigating Media Literacy: A Pedagogical Tour of Disneyland is an education playbook applied to the vast mediated universe of Disney. Readers of all ages can critically apply media literacy principles while still conscientiously participating as consumer-citizens, media creators, and agents of change. Media literacy is defined throughout this book as an instructional method rather than a political movement.

The book counterbalances the frequently myopic critiques of cultural scholars and the critical exemption granted by those across the world who find Disney to be a source of great pleasure. Integrated theory and practical examples allow readers to investigate of themselves and draw their own conclusions based on real inquisitive, observatory, and creative experiences that constitute media literacy (access, analyze, evaluate, create, reflect and act). Each chapter is ideologically mapped to an actual physical realm of Disneyland (e.g., Main Street, USA; Adventureland; Tomorrowland; Frontierland; Fantasyland). Each site provides a pedagogical playground for experimenting with each media literacy concept (e.g., context, audience, language, ownership, representation). The reader will come away with a deeper pedagogical understanding of how to cultivate media literacy using any context or subject—not just Disney. Each chapter includes discursive excerpts from students, along with assignments, discussion prompts, and classroom exercises, making it a valuable resource as a classroom textbook.

Perfect for courses such as: Media Literacy | Communication and Media Arts | Film Studies | Media History | Transmedia Studies | Business | Marketing

The book counterbalances the frequently myopic critiques of cultural scholars and the critical exemption granted by those across the world who find Disney to be a source of great pleasure. Integrated theory and practical examples allow readers to investigate of themselves and draw their own conclusions based on real inquisitive, observatory, and creative experiences that constitute media literacy (access, analyze, evaluate, create, reflect and act). Each chapter is ideologically mapped to an actual physical realm of Disneyland (e.g., Main Street, USA; Adventureland; Tomorrowland; Frontierland; Fantasyland). Each site provides a pedagogical playground for experimenting with each media literacy concept (e.g., context, audience, language, ownership, representation). The reader will come away with a deeper pedagogical understanding of how to cultivate media literacy using any context or subject—not just Disney. Each chapter includes discursive excerpts from students, along with assignments, discussion prompts, and classroom exercises, making it a valuable resource as a classroom textbook.

Perfect for courses such as: Media Literacy | Communication and Media Arts | Film Studies | Media History | Transmedia Studies | Business | Marketing

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Navigating Media Literacy by Vanessa E. Greenwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Teaching Methods. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Mapping Student Perspectives

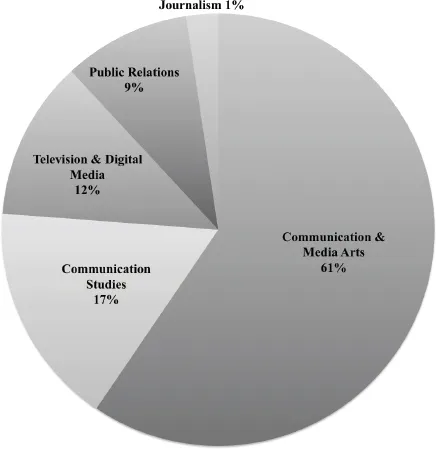

I BEGIN WITH the fundamental principle that educators teach students, not curriculum. This necessitates knowing as much about students as possible at the beginning of the semester. This chapter presents student self-reported data and autobiographical writing samples that together provide foundational information about their individual experiences, knowledge, attitudes, and values. These qualitative data provide fertile ground in which media literacy questions can take root. Figure 1.1 shows that the majority of students enrolled in this course were communication and media arts (CMMA)–degree majors.

Figure 1.1

Breakdown of Students’ Major Program of Study

CMMA is the most popular major within School of Communication and Media (SCM) at Montclair State University in part because the program affords students a diverse set of learning experiences across three categories of elective course work: critical/analytical, creative/conceptual, and applied/production. These three areas provide a well-rounded learning experience for students. They can choose course work across the fields of communication studies, journalism, television and digital media, and film. Along these lines, I conceptualized the course to integrate students’ critical, creative, and applied knowledge and skills—all three competencies requisite to media literacy.

Course enrollment data indicate a predominantly female (79%) and White (62%) student population.1 Students were ranked as either juniors or seniors in their program of study and therefore familiar with the routine of university life. Most of them were commuter students living at home (within New Jersey) and working at least one part-time job. Some of the students worked multiple jobs and were the first in their family to pursue postsecondary education. All of them were full-time students enrolled in at least 12 credits of course work during the semester.

These students were born in the mid- to late 1990s, which qualifies them as Generation Z or “Gen Z.” This demographic has been exposed since birth (in varying degrees) to the internet, social networks, and the mobility associated with smart devices (Francis & Hoefel, 2018). Their academic programs of study within SCM required them to be continuously engaged in transmediated experiences. As such, their lived experiences straddle online and off-line environments both inside and outside their university studies.

ACCESS AND ANALYZE:

GENERATING MEANINGFUL DATA

GENERATING MEANINGFUL DATA

Like most types of learning, media literacy education begins with activating prior knowledge. To learn more about these students, I crafted and administered an online survey questionnaire that asked the following:

•What is your chosen career path?

•Why did you choose to enroll in this course?

•What is one word that best describes you?

•If you won a million dollars, what would you do with it?

•How do you spend your time when you don’t have to do anything?

•Name one film that you have seen recently.

•What is your favorite childhood memory?

•What Disney character most closely resembles your character?

The data generated through the survey supplied me with preliminary information about student self-identity, media practices, and attitudes about and knowledge of Disney.2 Re-presenting some of these data back to students in aggregate form (to avoid singling out individuals) allowed me to situate their knowledge, experiences, and values within a wider social context and establish a foundation for other types of questions throughout the course.3

Media Literacy and Disney as Motivational Factors

It is not surprising that a majority of students reported taking the course solely because of their affection for Disney.4 More than 60% of students indicated Disney as the only reason they enrolled in the course. Illustrative responses include the following:

Because I love Disney! (Tia)

I registered for this course because I grew up being exposed to the Disney Channel my entire life. Now that I found that this course was all about exploring the world of Disney, it sparked my interest. (Kiara)

I am a huge Disney fan and I believe that watching the films have changed not only myself but also the world. (Iker)

Of responses, 20% cited both media literacy and Disney as the reason for enrolling in the course:

I am very interested in the world of media and I am very intrigued by applying Disney to media and learning different perspectives through that. (Chloe)

I liked the approach of applying media literacy to a universally well-known example such as Disney. I thought that by applying it to just Disney as opposed to a lot of little examples, it would help me understand the concepts in a more comprehensive way. (Willa)

I do not fully understand the concept of media literacy and I’m interested in the Disney brand; therefore, I figured this class would help me to foster and expand my knowledge of media literacy within the framework of a brand I am familiar with and can relate to. (Blakely)

The 20% of student responses that cited both media literacy and Disney were equally divided as to which one they privileged. Students who cited media literacy first may have simply crafted their response to mirror the course title rather than intentionally prioritizing interest in media literacy over Disney. It was difficult to discern. It is significant, however, that the first semester of this course occurred in the wake of the 2016 U.S. presidential election when the terminology fake news widely circulated. The idea of media literacy also gained traction during this time and most likely piqued student interest in the course. This is not to imply students have depth of understanding of what constitutes media literacy, however. A mere 10% of student responses (predominantly male) cited media literacy as the only reason for enrolling in the course:

I’ve always had an extreme interest in the critical analysis of media content. This course in particular caught my eye because I felt it would give me a different approach to understanding the role media can play in our society. (Dante)

I noticed the words “media literacy,” and I believe that is a discipline that should be taught to children from a young age. Since I am certainly no authority on the subject, I felt that I could benefit from the class and really learn about the subject. (Foster)

Through my time as a communication studies major I have learned many valuable skills such as how to understand media content as well as present some of my own. I believed this class will also present many valuable skills that aid me in dissecting media content. (Brennen)

Given that male students were the minority (21%) of course enrollment, it is also plausible they were inclined to downplay or even conceal their interest in Disney as something childish or feminine. I also acknowledge that as a female professor, my gender influences in different ways the attitudes, perceptions, and communication behaviors of both male and female students toward me, the course, and the subject of Disney (Basow, 1995; Miller & Chamberlin, 2000). That is not to say that the male students were uninterested in Disney. Female students may have also felt more comfortable disclosing to a female professor their authentic interest in Disney. The function of gender bias in the college classroom is complicated, and the research findings conflicting (Crombie et al., 2003). Nevertheless, I maintained a continual awareness of how student perceptions of gender and their communication about gender shape media literacy education in the context of Disney.

Student Self-Descriptors

Given the long-standing and significant correlation between student self-concept and academic achievement (Valentine et al., 2004), I wanted to know what students thought of themselves ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Copyright

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Mapping Student Perspectives

- Chapter Two: Touring the Realms of Media Literacy

- Chapter Three: Reconstructing History

- Chapter Four: Navigating Audience

- Chapter Five: Imagineering Language

- Chapter Six: Traversing Authorship and Ownership

- Chapter Seven: Dreaming of Representation

- Conclusion

- About the Author

- Index