eBook - ePub

Teaching Improvement Science in Educational Leadership

A Pedagogical Guide

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching Improvement Science in Educational Leadership

A Pedagogical Guide

About this book

A 2022 SPE Outstanding Book Honorable Mention

"Teaching Improvement Science in Educational Leadership is an essential pedagogic resource for anyone involved in the preparation and continued professional education of teacher, school, or system leaders. The authors are themselves leaders in the teaching of Improvement Science and in mentoring the application of the improvement principles to redressing racial and class inequities. They share here valuable lessons from their own teaching and improvement efforts."

Anthony S. Bryk, Immediate past-president, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and Author, Learning to Improve: How America's Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better

"Teaching Improvement Science in Educational Leadership is an essential pedagogic resource for anyone involved in the preparation and continued professional education of teacher, school, or system leaders. The authors are themselves leaders in the teaching of Improvement Science and in mentoring the application of the improvement principles to redressing racial and class inequities. They share here valuable lessons from their own teaching and improvement efforts."

Anthony S. Bryk, Immediate past-president, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and Author, Learning to Improve: How America's Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Teaching Improvement Science in Educational Leadership by Dean T. Spaulding, Robert Crow, Brandi Nicole Hinnant-Crawford, Robert Crow,Dean T. Spaulding,Robert Crow,Brandi Nicole Hinnant-Crawford,Robert Crow, Brandi Hinnant-Crawford, and Dean Spaulding in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Higher Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

A Pedagogy for Introducing the Improvement Science Method

The Personal Improvement Project

ROBERT CROW

Western Carolina University

Abstract

Many aspiring educational leaders may be unfamiliar with improvement science principles and frameworks. When developing leaders, like the ones enrolled in the doctoral program in which I teach, one approach for introducing improvement science principles and applications is through a learner-centered lens. The personal improvement project (PIP) provides such a lens for learners new to the concepts comprising the field of improvement science. The PIP is a learning exercise which affords an opportunity for students to engage in a novel experience, to use prior knowledge and already learned, personally relevant information to make connections to new concepts from the field of improvement science.

The ability to contextualize a problem is important for upholding the two improvement principles of making the work problem-specific and user-centered (Bryk et al., 2015). Further, constructing learning opportunities that students find personally meaningful, such as in the case of the PIP, is in step with cognitive theorists who pose that it is the successful learner who “links new information with existing knowledge in meaningful ways” (Sternberg & Williams, 2002, p. 446). Because the links between novel incoming information and one’s existing knowledge are integrative and mutually reinforcing, pedagogies that strengthen these associations enable learners to more readily transfer their newly acquired skills to novel tasks and situations. It is due to this transferability that I find the PIP to be an effective approach for introducing the improvement science method to developing education leaders.

The act of internalizing external frameworks is a cognitive activity. Learning theorists posit that the signs and symbols of the external environment, such as letters comprising the alphabet, become internalized over the learning period as cognitive structures and mental operations that are later called on based on cognitive demands (Wertsch & Stone, 1999). Therefore, the purpose of this chapter is to illustrate a pedagogy for achieving the learning outcome of internalizing the improvement method. Through engagement in the PIP, the principles and applications of improvement science can be learned through the lens of personal relevancy.

Background

In learning to use improvement science principles and applications in the educational setting, I have found it useful for my students to first develop a foundational knowledge base by viewing these elements through a personally relevant lens. Therefore, for the purpose of this chapter, I present a hypothetical example of a PIP focused on exercise and movement—or, more specifically, the problem of lack of personal motility. To further the example, the overall aim of my personal improvement initiative is to increase the relative amount of mobility in which I presently engage. To be more specific and in better alignment with SMART goals—that is, goals that specify measurable, time-bound outcomes—my goal is to increase overall engagement in high-aerobic activities such that I sustain at least 20 minutes of high-intensity cardiovascular activity four times per week. In this case, high intensity is considered activity that causes a minimum heart rate of 120 beats per minute (bpm).

Using Self as a Lens for Understanding the Problem

As mentioned, the PIP is an instructional exercise designed to allow learners to gain experience studying and applying improvement science principles and practices. As a whole, the PIP can take on a range of possible forms and foci. Regardless, all improvement initiatives should focus on the primary goal of answering the question What are you aiming to improve? Typical examples of students’ past PIP projects include topics that address the “too little of x” or the “too much of y” conundrum. As you might infer, the theme of too little of/too much of delineating the actual versus the ideal underlies most, if not all, improvement projects.

Stated earlier, the problem of a lack of motility in my daily routine represents a too-little-of condition, wherein through my goal to increase the behavior (in this case, it is sustained aerobic activity), I sought to rectify the discrepancy between the actual condition versus the ideal one (Archbald, 2014). Through the PIP, I launch the journey of overcoming my actual condition, one that did not involve any meaningful quantity or intensity of aerobic exercise, toward the ideal state, a (somewhat) regular exercise routine that ought to be included in my daily schedule.

The pathway to achieving the goal sounds elusive, and at first glance it is. However, through an improvement lens, students come to understand and address their problem by employing techniques such as systems and/or process mapping and causal systems analysis. They envision and enact ways toward solutions through driver diagramming and plan-do-study-act cycles. Through engagement in the PIP, an in-depth modus operandi can develop that will, with time and practice, become an internalized orientation to practical problem finding and solving.

What’s the Problem?

A primary activity I like to introduce in my classes early in the PIP is problem exploration. A major part of this exploration is in establishing a problem definition. The 5 Why’s is one of several techniques I have found useful for addressing the rationale and justification supporting problem definition and framing (Bryk et al., 2015). Using the PIP topic focused on motility, one might begin by asking the first of a series of Why questions with: Why is too-little-of, or too-much-of, x a problem? Or, as it is in our case—Why is a lack of motility a problem? As a possible response, one might postulate, based on the use of the 5 Why’s technique, that because of a lack of strenuous and sustained exercise, the heart does not receive cardiovascular benefit. Why is a lack of cardiovascular activity a problem? According to the American Heart Association (n.d.), 20 minutes of sustained cardiovascular activity per day is recommended in order to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Consult Table 1.1 for help with the process of defining the parameters of the problem, adapting descriptors for one’s personally relevant PIP.

Table 1.1. An Improvement Science Lens for Actionable Problems of Person

| Urgent for the self | Problem arises out of a perceived need by the person affected and can be sourced from personal record collecting and keeping |

| Actionable | Problem exists within the individual’s sphere of influence |

| Feasible | Problem prioritization can occur that considers time-frame and resources |

| Strategic | Problem is connected to the goal of the individual affected |

| Tied to a specific set of practices | Problem is narrowed to high-leverage practice(s) yielding incremental new learning through plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles |

| Forward-looking | Problem reaches toward the next level of improvement— scaling up and sustainability |

Note: The construct “problem of person” (the focus of the PIP) replaces “problem of practice.” Source: Adapted from Perry et al. (2020).

What’s Causing the Problem?

Once the issue has been identified, the underlying root causes contributing to the so-called problem can be identified. Problem identification fulfills an essential improvement principle: see the system producing the outcome (Bryk et al., 2015). Once identified, the improver goes on to conduct a causal systems analysis to articulate the set of underlying, or root, causes found to be responsible for that problem’s existence.

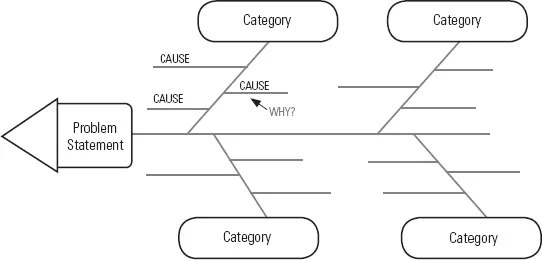

Figure 1.1 depicts the general structure of the causal systems diagram, consisting of the problem statement and the major and minor contributory root causes determined to be responsible for perpetuating the problem at hand. The fishbone diagram is composed of specific elements. The first and perhaps most notable feature is the problem statement. The problem statement is expressed in the left-hand area (or head of the fish skeleton) in the diagram. Contributing factors, or more correctly, the root causes found to be responsible for the existence of the problem, appear respectively in the areas represented by the word Category. Each category of root causes is then further deconstructed into discrete, granular elements comprising that category. Upon conclusion of the causal systems analysis work, the finished diagram provides stakeholders with a nearly complete roadmap that highlights the causal factors that need to be addressed in the next phase of the improvement project—determining which changes might be introduced that could lead to improvements.

Figure 1.1. Causal systems diagram (a.k.a. fishbone diagram).

Causal systems diagramming is an important technique for creating an understanding of the problem context (ultimately, a shared understanding if undertaken collaboratively). The diagram functions as a means for collecting and organizing current knowledge about the underlying causal factors found to be responsible for perpetuating the problem at hand (Langley et al., 2009). The causal analysis requires improvers to “direct attention to the question, Why do we get the outcomes that we currently do?” (Bryk et al., 2015, p. 198).

One may undertake a causal systems analysis (CSA) in a variety of ways. In the case of the PIP illustration, we will construct a fishbone diagram. Doing so allows one to pinpoint contributory root causes underlying the problem at hand. During the process of constructing the diagram, distinguishing the set of root cause(s) responsible for the existence or perpetuation of a problem can be garnered from several sources. While not exhaustive, one can turn to at least three avenues for determining root causes—(a) through findings and other results in the published literature, (b) by tapping into the local knowledge base, and (c) through stakeholder engagement and dialogue, as follows:

Literature scan (and other published information)—published results and other findings appearing in peer-reviewed journals and other scientific papers

Local knowledge (including anecdotal)—leaders’ years of experience, professional organizations and networks, institutional data

Stakeholder engagement—variety of first-person perspectives of experiences

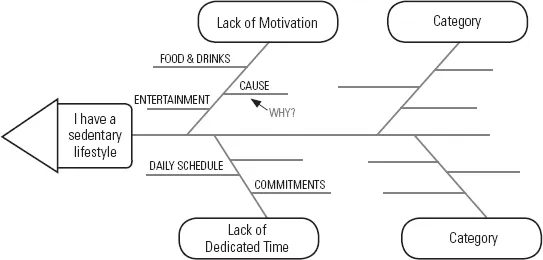

From our PIP example of increasing opportunities to engage in an elevated cardiovascular rate, much can be learned by exploring the underlying causes hampering engagement in strenuous activity. The underlying elements are the actual root causes contributing to the existence of the problem at hand. The causal analysis technique, employing the fishbone diagram (also called the Ishikawa diagram), allows individuals or groups to construct a visual depiction of the host of contributory factors and their relative subsets found through literature scans, local knowledge and data, and stakeholder voices closest to the problem.

When introducing the CSA as new material to be learned, I emphasize that in professional practice the technique is by no means to be undertaken independently. Construction of the diagram is intended to be a collaborative endeavor. Myriad voices of relevant stakeholders, as well as other sources of information, should inform the diagram’s final rendering. Later, when we discuss ways to develop the “it takes a village” mindset for how to overcome the various causal factors, it is important to remember to delegate where, taken one by one, the strategy for tackling the various challenges might occur when each “category” (or bone in the fish diagram) can be delegated to specific staff or a particular unit. These independent units could then, in turn, take on the particular component in the improvement initiative. Selection of those responsible for proaction should be strategic and consider the following questions—Who can get the most leverage? Who has the most social capital?

Further, in the case of the PIP, causal factors may not be in the immediate control of the person completing the project. Careful consideration can reveal which causal factors are within grasp (and thereby best addressed during the project) and which ones are not, which challenges have the greatest potential for returns and which do not, and so on.

As shown in Figure 1.2, the problem statement is written in measurable terms. Conversely, one may transpose the negatively phrased problem statement into a positively phrased aim statement focusing on an aspect of improvement. The categorical factors (represented by the larger bones in the fishbone diagram) can be considered by the improver in relation to leveraging access, social capital, and personal volition, so that through transposition, a workable set of prioritized actions can be constructed to target these deterrents (i.e., causal factors).

Figure 1.2. Fishbone diagram illustrating causal factors for lack of motility.

In addition to undertaking the causal analysis, there are other improvement techniques that one might employ. For example, and also in an effort to see the system, one might use a sys...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction The Need for Curating a Repertoire of Improvement Science Pedagogies

- Chapter 1. A Pedagogy for Introducing the Improvement Science Method: The Personal Improvement Project

- Chapter 2. Who Is Involved? Who Is Impacted? Teaching Improvement Science for Educational Justice

- Chapter 3. Finding Problems, Asking Questions, and Implementing Solutions: Improvement Science and the EdD

- Chapter 4. Teaching the Design of Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycles Using Improvement Cases

- Chapter 5. Embedding Improvement Science in One Principal Licensure Course: Principal Leadership for Equity and Inclusion

- Chapter 6. Embedding Improvement Science in Principal Leadership Licensure Courses: Program Designs

- Chapter 7. The Essential Role of Context in Learning to Launch an Improvement Network

- Chapter 8. From Learning to Leading: Teaching Leaders to Apply Improvement Science Through a School–University Partnership

- Chapter 9. Empowering Incremental Change Within a Complex System: How to Support Educators to Integrate Improvement Science Principles Across Organizational Levels

- Chapter 10. Aligning Values, Goals, and Processes to Achieve Results

- Chapter 11. Toward a Scholarship of Teaching Improvement: Five Considerations to Advance Pedagogy

- About the Authors

- Index