![]()

PART ONE

INTRODUCTION TO LEARNING IMPROVEMENT AT SCALE

![]()

1

LAYING OUT THE PROBLEM

Despite the decades-long history of assessment in higher education, little evidence indicates that assessment results in improved student learning. To understand why this is the case, we must first develop a common language for discussing learning improvement at scale. We then provide a historical overview of higher education and the assessment thereof and provide explanations for the lack of evidence of learning improvement in higher education. The chapter concludes with an outline of this book’s structure, mission, and goals.

What Is Learning Improvement at Scale?

This book is a step-by-step guide for improving student learning in higher education. We focus on improvement efforts at scale. Each of these terms—student learning, improvement, and at scale—requires explanation.

By learning, we mean the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that students acquire through education. Learning can occur in broad, general areas like writing, ethical reasoning, art appreciation, and oral communication. Learning can also occur in discipline-specific areas like functional anatomy, corporate law, fluid dynamics, and sculpting, or in attitudinal and behavioral domains such as sense of belongingness and ability to collaborate with diverse peer groups.

By improvement, we mean demonstrated increases in student knowledge, skills, and attitudes due to changes in the learning environment (throughout this book, we will refer to these changes as interventions). Of note, to move the needle on skills like ethical reasoning or corporate law requires powerful intervention that often spans multiple courses.

To demonstrate such improvement, one must gather baseline data, change the learning environment, and reassess to determine student proficiency under the new learning environment. The comparison of the baseline data and the reassessment must show that students who experienced the changed learning environment perform better than students who did not. We refer to this general methodology—assess, intervene, reassess—as the simple model for learning improvement (Fulcher et al., 2014).

As a basic example, imagine that biology faculty were concerned with the bone-identifying abilities of students graduating from their program. They presented senior students with a computer-based skeleton model and asked them to identify as many bones as they could. On average, suppose that they found the assessed group of seniors were able to identify 135 out of 206 bones. This measurement would provide the baseline estimate of student bone-identification proficiency. The faculty could then modify the curriculum, emphasizing practice with identifying bones and providing feedback about students’ bone-identifying abilities (constituting a change in learning environment). Then, imagine that the next cohort of students, all of whom had experienced the new curriculum, was reassessed and found to be able to identify an average of 197 bones. This would represent a 62-bone improvement over the previous cohort (i.e., the reassessment showed better performance). In this situation, the evidence would demonstrate that learning improvement has occurred.

In earlier work, we noted that higher educators often confuse the words change and improvement (Fulcher et al., 2014). People are often excited to label as an “improvement” any modification assumed or expected to be useful, even in the absence of proof that the modification leads to a better outcome than its predecessor. Using the bone identification example, the faculty members might prematurely (and incorrectly) claim that learning improvement has taken place as soon as curricular modifications are made. However, we would argue that faculty members merely made a change to the learning environment at that point. Only after reassessment demonstrates better learning (the 62-bone increase in students’ average identification ability) than occurred under the old curriculum can faculty claim that the change had actually been an improvement.

We have also found that the issue of scale is often overlooked in improvement efforts. While individual faculty members frequently work to make their courses better, coordinated efforts that stretch across entire academic programs are much more rare. When we refer to learning improvement “at scale”, we mean improvement efforts that span an entire program, affecting all affiliated students. What is considered a “program” is likely to vary across institutions. For the purposes of this book, we consider “programs” to be academic structures that have the following characteristics:

• They require a consistent set of experiences, such as a set of mandatory core courses.

• They require students to engage with the set of experiences over an extended time period (usually multiple semesters).

• They are intentionally structured to achieve some outcome (or, more likely some set of multiple outcomes).

Generally, when we discuss academic programs, we intend for our readers to envision academic degree programs or general education programs. University structures, of course, are widely varied; other types of programs, such as some academic minors, may very well fit these requirements. Similarly, some academic degree programs might not fit these requirements (e.g., customizable majors with few or no required courses or predetermined outcomes).

Given a simple program structure, it is technically possible to achieve learning improvement at scale with a single section of one course. For instance, imagine a small program that graduates 20 students per year. Many of the courses consist of only one section taught by one faculty member. If an instructor in such a position made a change to the learning environment in the single course section, all 20 students would be affected. In this special case, making a change to one course section affects all students in the program. If those students did learn more as a function of this change, then learning improvement at scale would be achieved.

While we acknowledge this possibility, we emphasize more complicated learning improvement at-scale efforts. We find that faculty and administrators particularly struggle to conceptualize and implement multisection, multicourse improvement efforts. Further, for many complex skills like writing, students benefit from exposure to vertical interventions weaving through multiple courses throughout a program’s curriculum. It is unsurprising that ambitious, wide-reaching improvement efforts like these would pose difficulty in their organization and implementation. This is precisely the problem we hope to address. Thus, this book especially emphasizes the strategies associated with complex cases of learning improvement at scale.

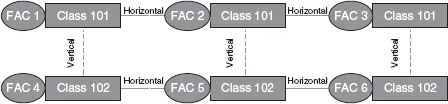

Let’s continue with the biology example to illustrate an effort that occurs at scale with a complex structure. The biology program graduates 150 students per year; therefore, learning improvement at scale should focus on developing and implementing interventions that affect all 150 students. Furthermore, the faculty felt that the skill was challenging enough that it could not be adequately addressed in just one course. Therefore, the proposed interventions for bone identification spanned two required courses, 101 and 102. Further, imagine that each of those courses is composed of three sections (each of which enrolls 50 students), and that these six sections are taught by six different faculty members. This scenario is displayed visually in Figure 1.1. Each oval represents a different faculty member, while each rectangle represents a different course section.

In this context, pursuing learning improvement at scale would require all six faculty to integrate their work through a process we will refer to throughout this book as alignment. Faculty demonstrating alignment are coordinated with each other in their approach to teaching. Horizontal alignment means that all faculty teaching sections within the same course work collaboratively and have agreed on a common set of outcomes and common strategies to accomplish these outcomes. In our biology example, the three faculty members teaching 101 would need to demonstrate horizontal alignment with each other, as would the three faculty members teaching 102. In Figure 1.1, horizontal alignment is demonstrated by the dotted horizontal lines linking across sections within a course. Note that horizontal alignment can be viewed on a spectrum where utter alignment means every faculty member does everything in a lock-step manner (which we rarely advocate). On the other extreme, with no alignment, sections bear almost no resemblance except for the course name.

Vertical alignment refers to the connection among sequential courses that are meant to build on one another in the service of program-level outcomes. In Figure 1.1, vertical alignment is demonstrated by the dotted vertical lines lining sections of 101 with sections of 102 (note that this is, of course, a simplified visual representation: All sections of 101 would need to be vertically aligned with all sections of 102, necessitating strong horizontal alignment between sections within each course). Strong vertical alignment enables seamless scaffolding as a student progresses through a program. Faculty members in earlier courses prepare students for downstream success. And, faculty in later courses of a sequence can count on students having certain skills when they enter the classroom.

Figure 1.1. Horizontal and vertical alignment.

Source: Fulcher, K. H., & Prendergast, C. O. (2019). Lots of assessment, little improvement? How to fix the broken system. In S. P. Hundley & S. Kahn (Eds.), Trends in assessment: Ideas, opportunities, and issues for higher education (p. 169). Stylus.

In this case, no single faculty member would have the ability to improve the learning of all students. For example, if only faculty member 2 (who teaches 101, section B) made substantial adjustments to her section, only 50 of 150 students would be affected. Although faculty member 2 would deserve commendation, learning improvement at scale would not be achieved. Only one third of the students would receive an intervention. Furthermore, even those students would have only received the intervention in one course (101), not in both courses (101 and 102) as intended.

Now, imagine if a learning improvement initiative were attempted for all undergraduates of an institution. If 1,000 students are in each graduating cohort, then the interventions would need to reach all 1,000 students. As opposed to six faculty members, as in the biology example, dozens of faculty members would likely need to coordinate with each other. This kind of large-scale collaboration is necessary for most learning improvement initiatives, and it is with these situations in mind that this book was written. The subsequent chapters will attempt to illuminate considerations and strategies for implementing program-wide improvement efforts.

Contrasting Our Purpose With Another Type of Improvement

In the assessment literature, a growing trend is to speak of “real-time” assessment (Maki, 2017). The thrust of real-time assessment is to focus on current students by collecting data and making changes to the learning environments the students experience. This differs from the type of improvement discussed in this book, which involves collecting data on current students as a baseline, and then making changes to the learning environments that affect future students.

We acknowledge that institutions and the faculty and staff within them should do what they can to help current students. Research has demonstrated the benefits of consistent, timely, and explicit feedback for students’ learning (e.g., Evans, 2013; Halpern & Hakel, 2003). Nevertheless, in some circumstances, “real-time” change efforts are not feasible. As a rule of thumb, the larger and more comprehensive a learning improvement effort, the less likely a real-time approach is to work. The following four learning scenarios, loosely based on our own experiences, illustrate this point.

Scenario 1

Two instructors collaborate to teach the two sections of an introductory statistics course. Weekly, they administer cognitive checks to gauge students’ learning. The instructors find that most of their students struggle to differentiate the standard deviation from the standard error of the mean. The faculty assign a short video that differentiates the concepts, and then have all the students email the instructors a brief description of the difference between the two concepts in their own words. A few weeks later, 90% of students correctly explain the concept on the midterm exam. This is an example where an initial assessment and pointed feedback likely contributed to better learning by the same set of students. In other words, real-time assessment is working as it should.

Scenario 2

The same two faculty as in scenario 1 receive disconcerting news midway through the course. A colleague who runs the department roundtable noticed a hole in students’ statistics skills. The colleague, playing the part of a clie...