![]()

PART ONE

STUDENT LEARNING AND ASSESSMENT

![]()

1

THE EVOLVING MEASURE OF LEARNING

Bill Moseley and Sonya Christian

Bakersfield College, one of 115 California Community Colleges, has been an active part of the evolution of assessment practice since the 1990s. Early on, this evolution was marked by the development of student learning outcomes, which were mapped to program outcomes for the purpose of an aggregated calculation of program assessment data. The introduction of institutional learning outcomes broadened the scope of assessment practice by making an explicit connection to the college’s institutional values and mission. Later, technology assisted in both the scale and the depth of analysis of the assessment data. The introduction of microcredentials, also known as badges, as discrete representations of knowledge or skills provided an opportunity to better align assessment with both instruction and career objectives. Bakersfield College is integrating badges with the assessment framework at the student learning outcome level, to leverage assessment practice as the criteria for the awarding of badges. This integration provides a means of recording and communicating discrete academic achievement. These badges empower and extend the value of assessment data by communicating it in meaningful ways to students, other institutions, and future employers.

The Context for Change

Bakersfield College serves over 40,000 students in the central and south San Joaquin Valley. Founded in 1913 with 13 students, the college is a Hispanic-Serving Institution, with 70.6% of students belonging to this ethnic group. While many students reside in the City of Bakersfield, a significant number live in the rural areas and smaller towns throughout Kern County. The college maintains a physical presence in several of these outlying areas and supplements offerings with a comprehensive distance education program.

This chapter addresses the evolution of student learning and assessment over the last 30 years, from 1990 to 2020 and beyond, in 3 eras. The first, from 1990 to 2010, was characterized by the development of assessment strategies in higher education. During the second era, from 2010 to 2018, there was advancement of new tools and technologies to support the development and execution of assessment. The third era begins in 2018, and continues to the present day and beyond. This era is characterized by a synthesis of innovative ideas about knowledge and assessment with new technologies that enable these ideas to reach full potential.

Development of Assessment Strategies 1990–2010

Early advances in assessment were driven by the recognition that, in order to evaluate the effectiveness of educational programs, some quantification of learning beyond grades and units was necessary. From the early 1900s to the 1970s, the focus had been on scalable, standardized assessment of learning through objective examinations given to graduating college students.

But as we saw at the end of the 1970s, objective testing was not the way faculty members wanted student learning to be assessed. They were more comfortable with open-ended, holistic, problem-based assessments, which were more in tune with what they thought they were teaching. (Shavelson, 2007, p. 30)

Faculty members believed that assessment practice needed to be more tightly coupled with their teaching. Driven by parallel growth in action research methodology, the assessment movement grew out of the academy’s desire to direct their own assessment work in ways that were relevant to, and connected with, teaching and learning. In 2006, the Secretary of Education’s higher education commission recommended that higher education should “measure and report meaningful student learning outcomes” (Shavelson, 2007, p. 30).

The college’s assessment committee was formed in 2010 and led by the Academic Senate. Programs were required to use student learning outcomes (SLOs) in the course outline of record to guide instruction and assessment. These SLOs were mapped to higher level program learning outcomes (PLOs), which represent the key learning outcomes at the program level. In practice, however, the measurement of student performance on SLOs was often situated as an “add-on” to the core instruction and learning assessment in the class, leading faculty and students to feel that the SLO assessment was not connected in an authentic way. Faculty began to recognize a need for a tighter integration of SLO assessment with the core teaching and learning assessment practices employed at the course level.

Advancement of Tools and Technologies to Support Assessment 2010–2018

In the period between 2010 and 2018, growth and change in the universe of assessment was driven and characterized by the introduction of technology. Technology had two impacts on assessment. First, it facilitated the scaling of assessment work by providing internet-connected platforms for managing the large amounts of data generated by assessment, and in some cases, the delivery of the assessments themselves. The second impact provided a mechanism for more advanced analysis of the data at an institutional level. Assessment data could now be analyzed, disaggregated, and deeply understood in ways that were not easy or even possible before. The byproduct of these enhanced capabilities was integration of assessment with accreditation standards, which represented the last stage in the assumption of ownership by the academy. This ownership was driven by the desire to maintain a self-regulated system of learning, in contrast to other systems of education that are regulated and assessed by government agencies.

The work of Guided Pathways (Bailey et al., 2015) was the dominant framework for a college-wide redesign effort that resulted in the faculty-led refinement of programs of study, starting with the end in mind. Using PLOs as the overall target, faculty looked critically at the alignment of curriculum and SLOs. Clarifying both the learning and the path to program completion created a coherent curricular pathway for students and a fundamental shift in how faculty viewed the student journey through courses toward program completion. Given this shift, the traditional cafeteria-style course catalog was no longer an adequate tool for communication to students. In partnership with the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO), the college developed Program Pathways Mapper (Bakersfield College, n.d.), an online visualization tool that starts with the program learning outcomes and the careers available, along with salary information. The visualization tool is currently being used by 30 community colleges in California and is being scaled up to the California State University (CSU) System.

Bakersfield College has seen gains in student achievement as a result of its detailed curricular mapping to baccalaureate completion at CSU Bakersfield (CSUB). During the past 5 years, the number of transfer students from Bakersfield College to CSUB who complete a bachelor’s degree has increased by 19%. Of Bakersfield College students who transfer to CSUB, 47.7% complete their program in 2 years, compared to 42.4% of all students transferring to CSUB and an even smaller CSU system-wide rate of just 32.6%.

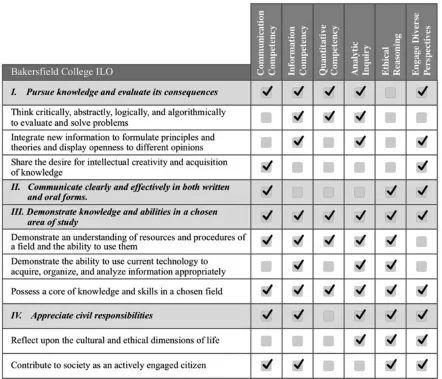

The guided pathways movement has positively influenced governance structures. Bakersfield College intentionally designed the committee structure to ensure continuous, systemic evaluation and improvement of the quality and currency of all instructional programs. The Program Review Committee, working in conjunction with the Accreditation and Institutional Quality Committee, the Assessment Committee, the Curriculum Committee, and individual departments, provides a robust integrated framework for quality assurance. The tight integration resulted in a deeper understanding of how all the different parts play a role in the ultimate goal of improving student learning and student achievement. The system now ensures regular and systematic review of all courses and programs, alignment of content and teaching strategies with current best practices, and ensures that all learning outcomes are relevant and appropriate. Finally, this integrated system ensures that the four institutional learning outcomes (ILOs)—think critically, communicate effectively, demonstrate competency, and engage productively—are assessed broadly and regularly. By confirming clear alignment of all course-level SLOs to the college’s ILOs, Bakersfield College is able to assess and monitor student attainment of ILOs. Further, transfer rates and job placement data provide concrete evidence of student attainment and practical application of ILOs.

Although the college’s ILOs do not use the specific language of the accreditation standard, Figure 1.1 shows the alignment.

Bakersfield College’s assessment committee is the primary agent responsible for ensuring the definition and assessment of all outcomes at the course, program (including a baccalaureate degree), and institutional levels. The assessment committee works with the curriculum committee to ensure that all course outlines of record have appropriate SLOs. The assessment committee works with the program review committee to ensure that PLOs are assessed as part of the program review process. The intentional design of the formal governance structure at Bakersfield College ensures dialogue among the faculty about creating, updating, and assessing learning outcomes at all levels.

Innovation of Badging and Assessment 2018–2020 and Beyond

In the early 21st century, the technology sector began experimenting with microcredentials, or badges. Digital badges were born in the world of video games, where these digital achievements were originally mapped to specific tasks and accomplishments in games. In this context, badges were used as a game mechanic, to influence and motivate movement toward specific tasks and goals desired by the game’s creator, especially at times where the game itself might lack the tools or structure to move a player in that direction (McDaniel, 2016). As this mechanic became popular and the idea of gamification spread to education and the workplace, badges began to appear elsewhere. Mozilla and other organizations developed standards for open badges, allowing badges to be compatible with one another, regardless of their source.

Figure 1.1. ILO to accreditation language mapping.

The platform of microcredentials, when used to record and convey student skills that are captured in student learning outcomes and measured by authentic assessment techniques, presents a unique opportunity for the evolution of credit for learning. The alignment of platforms, ideas, and current assessment practice with powerful and usable technologies has set the stage at Bakersfield College to develop a higher resolution picture of each student’s learning—one that can travel with them throughout their educational career, and into the workplace.

The Carnegie Unit as the Problem

In 1906, the Carnegie Foundation created the Carnegie unit as a means of defining both a “high school” and a “college,” with the goal of ensuring student qualifications for college entrance and also developing a standard for the funding of pensions for college faculty, who at the time did not have retirement plans funded by their institutions. Even at the time of its creation, the Board of Trustees for the Carnegie Foundation expressed multiple concerns with the possible negative implications of the move to equate a unit measurement of learning with hours spent in a classroom. A report by Tomkins and Gaumnitz (1964), written several decades after the launch of this idea, said:

The Carnegie Unit, unique to the American system of secondary education, is being reexamined. Is it outmoded? Do the far-reaching changes occurring in the objectives of secondary education, in the number and types of pupils attending, in the high school–college relationships—to name only a few—call for new methods and instruments of pupil evaluation and accounting? (p. 1)

Sixty-five years have passed since this report was published, and more than a century since the inception of the Carnegie unit, and yet it is still the predominant model for the representation of learning in higher education.

In Degrees That Matter, Jankowski and Marshall (2017) remind us that “Seat time and credit accrual are only proxy measures for student learning; they say nothing about what students have learned while sitting in their seats or in the process of accruing their credits” (p. 56). The assessment movement, which gained momentum in the 1970s, holds some hope in terms of measuring student performance in the class context, but has yet to make that data a part of the individual student record, or transcript. As such, students may never be aware of the outcomes they have mastered in the course of learning that never appear on the transcripts: a missed opportunity to provide specific feedback to students on the critical points of learning at the course level. In fact, many institutions still struggle to disaggregate their assessment data by individual student demographics because they do not have data recorded at the individual student level, but rather aggregated at the course level. The current system of communicating what the student has learned (skills and abilities) from the institution is still the transcript. A transcript typically contains three typ...