![]()

PART ONE

IN SEARCH OF MIDCOURSE CORRECTION

Discovering the SGID

![]()

1

THE SGID

One day during my first college teaching job, years ago, I was sharing a meal with a group of students from one of my courses. They had volunteered to provide regular feedback to me so we could alter the nature of our course as we progressed through it, engaging in some corrections as we saw fit. After a long-winded explanation for some approaches I use, one of the students chimed in with a comment that I perceived to be mixed with a bit of admiration and surprise: “You must really think a lot about teaching.”

She was right. I do think a lot about teaching. And I have also been fortunate over the years to have the opportunity to speak about teaching with others and write about it in a scholarly way. About a decade later this would lead me to become the senior associate director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at Colby College, where this book you’re reading took form.

I do think a lot about teaching. But here’s the thing: Most teachers think a lot about teaching. Most teachers have reasons for the assignments they have designed, the ways they approach class time, and the readings they select. Most teachers think and care a lot about teaching. My student was right about me, but little did she know, she was right about almost all the teachers I have ever met.

This idea was swirling around in my brain when I sat down to give my first SGID consultation with a faculty member at Colby College on a chilly morning in October of 2018. I think a lot about teaching, but he probably does too. What makes me the “expert,” particularly in his course? Why am I the one on this side of the table, not the other way around?

Then I regrouped. I wasn’t coming into his office empty-handed. Just the day before I had conducted an SGID in his classroom, where some conversations ensued, and they gave me some of the most thoughtful feedback I’d ever heard about a course. His students shared with me what they found confusing, where they struggled with readings, and what they had forgotten was in the syllabus (until a neighbor reminded them). But it wasn’t all bad news. They shared with me, too, how their instructor’s enthusiasm for the subject was contagious, and they were surprised at how much they connected with the material, and him. They told me the truth about their course.

Before our consultation meeting, I typed up a report containing his students’ ideas and constructed some key themes that described our conversation. I wasn’t coming into this consultation empty-handed. I had the truth with me, at least as his students saw it. Although I find the idea that I’m some expert on teaching debatable, what’s not debatable is that, at that moment, I was the expert on how his course was going for his students. Perhaps I was more of a conduit for students’ ideas than an expert. In that spirit, this instructor and I proceeded to have a conversation for about an hour about what his students were seeing in their course, what ideas and corrections midway might be helpful, and how to have a frank follow-up conversation with students about what the rest of the semester could look like. We imagined the great potential the second half of this course had for his students, and developed a plan for how to realize that potential. That’s the bright side of all courses. Even if they have a not-so-stellar first half, they can have a brilliant second half. And everyone will appreciate the improvements.

Was I some kind of expert, or was I some kind of conduit? Who really knows? But what this instructor and I knew was that now he had some insightful ideas about how to work with his students to refocus on the priorities of the course for the remainder of the semester. And when I left that first consultation I knew that I could rely on the SGID process to bring out the kind of feedback instructors need to do right by their students. Whether you’ve been teaching a long time or a short time, whether you’re the director of a CTL or a first-time instructor, SGIDs will improve the learning environment for your students.

—Jordan D. Troisi

Gathering effective feedback about college courses from students doesn’t require years of expertise or a prestigious title. What it does require is a willingness to have conversations with and listen to the voices of students and instructors. Succinctly, this is what the SGID process is.

We think anyone can do this, and we will call this person who gathers this information the consultant. But don’t be intimidated by the label. We think directors or staff of CTLs can serve as consultants, and our survey data with over 200 responses show that many of them do, but we also think seasoned and new instructors can be consultants as well, and many of them do. It’s a role we play, not a full-fledged job we have. And your job title and duration of experience in the classroom matter a lot less to filling this role than does your willingness to follow a decades-old process designed to elicit the real feedback—not evaluations—students want to give to improve their educational experience. For those brand new to SGID, this chapter will provide a valuable procedure and sequence for conducting a single SGID. For those already experienced with SGID, we hope to give you food for thought as we elucidate a specific approach to conducting the process based on its storied past. At times we will draw directly from approaches to conducting SGID that exist in peer-reviewed articles and the data we have from our recently collected survey of educational development professionals (including many full-time faculty members), but at other times, we will draw more from our own approach to conducting SGID in our practice and in the classrooms at our schools. With this in mind, we think this chapter has something for everyone—whether you know this topic well or not at all, whether you have a lot of SGID experience or a little, whether you’ve been teaching for 20 years or 2 years.

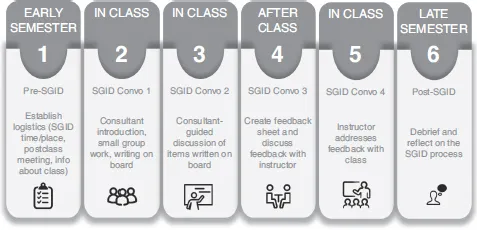

To help conceptualize the process of conducting a single SGID, we have constructed an infographic (see Figure 1.1). In a nutshell, there are six general phases to the SGID process. The first phase includes tasks that happen before the SGID classroom visit occurs, including things like scheduling the SGID session. Then during the classroom visit two conversations occur: SGID Conversation 1 (Students & Students) and SGID Conversation 2 (Students & Consultant). During these conversations the students will discuss the factors impacting their learning in the course, and the consultant will seek clarifying information from the students. After the in-class SGID session has ended, the consultant will meet with the instructor to have SGID Conversation 3 (Instructor & Consultant) and talk with the instructor about what transpired during the in-class session. After this meeting between the consultant and the instructor, the instructor will follow up with students about the nature of the feedback, which is SGID Conversation 4 (Instructor & Students). Finally, it can be helpful to engage in a post-SGID phase to provide concluding components of the overall SGID process, such as evaluation of the SGID process by the instructor(s) who took part, or some more informal debriefing session about how the process went.

Figure 1.1. Overall SGID process.

Before we delve too deeply into specifics about the SGID process, we think it is worth identifying some reasonable expectations for the people involved in the process. Students can expect to provide their honest feedback about what is helping and hindering their learning in the course, to discuss this feedback with their student colleagues and the consultant, and to eventually hear back from the instructor about how the class might engage in some corrections, alterations, or reminders in light of the feedback. Students should not expect that they can identify a litany of changes in the course that will be accepted wholesale by their instructor. Instructors can expect to receive honest feedback from their students about their learning, as framed by the consultant’s view of the conversation that ensued during the class. They should be open to hearing the feedback, understanding where it fits with their pedagogical goals, and making reasonable corrections to the course for the remainder of the semester, or perhaps after the semester has wrapped. Although often overlooked, we think consultants also have much to gain from the process of engaging in SGIDs. Consultants should expect to listen to students, engage students in conversations about teaching and learning, and to be a conduit for the information, rather than an all-knowing problem-solver. Consultants can form connections with colleagues, come across new pedagogical techniques, and glean a better understanding of academic culture at their institution. We will explore the potential impacts of the SGID on all involved in greater depth in later chapters.

In the following sections we will detail some specific recommendations for each phase of the SGID process. For those who are new to SGID, these sections will give you all the nuts and bolts that you need to make SGID happen, either in your courses, or at your institution more broadly.

The Pre-SGID Phase

The first phase of the SGID process involves having the consultant work with the instructor to establish SGID logistics, and familiarize the consultant with the instructor and the course at hand (see Figure 1.2). If you are serving as a consultant for your friend who’s an instructor down the hall or in the next building over, these steps might not require much effort, and could be done face-to-face or over email. (See Appendix B for an email template from Grand Valley State University.) But addressing these items will help you get set up to conduct SGIDs (see Table 1.1).

Figure 1.2. Early semester—The pre-SGID phase.

When should you schedule the postclass consultation? We recommend having it come soon after visiting the class. The more recently the consultant has visited the class, the more vivid memories of the classroom observation and discussion with the students will be. Having this consultation shortly after the class visit also allows the instructor to readily recall issues that may have been relevant to the class at the time of the SGID session, such as distribution of recent feedback on assigned work. The more focused the consultant and instructor’s minds can be to the time period in which the SGID took place, the easier it will be to understand the feedback about it.

TABLE 1.1

Pre-SGID Checklist

✓ Determine where the class meets and when.

✓ Establish the precise time, during the middle of the semester, in which the SGID session will take place.

✓ Start the scheduling process for the postclass consultation with the instructor as soon after the class as possible (i.e., find available meeting times).

✓ Provide an opportunity for the instructor to share information about the course, including sharing the syllabus.

During this first pre-SGID phase there are also opportunities for the instructor to describe idiosyncrasies of this course, this group of students, and the instructor’s syllabus and learning objectives. The original descriptions of the SGID anticipated this discussion would occur face-to-face (e.g., Clark & Redmond, 1982), but with increased pressures on time and the proliferation of both basic and advanced technologies—like email and web conferencing—these days this discussion often occurs electronically. If you decide to gather detailed information before the SGID in-class session, we find it valuable to consider questions that allow for inquiries into the course structure, the nature of the students in the course, and the strengths of the instructor. These types of questions will provide a fairly comprehensive view of what consultants will need to know, and they also frame the SGID process as a ...