![]()

1

Foundational Grounds of Event Leveraging

1.1 The Study of Event Leverage: Integral Reasoning and Cross-boundaries

Event leveraging as a distinct theoretical framework was conceived and introduced by Laurence Chalip in his pioneering model published in 2004 that prescribed the economic leverage of sport events (Chalip, 2004). The model was inspired by, and based on, research that examined the Gold Coast IndyCar race (Chalip and Leyns, 2002) and the experience of the Sydney 2000 Olympics (Chalip, 2002; Faulkner et al., 2000). In fact, the Sydney Olympics was one of the first mega-events to implement a concerted set of strategic actions and programs to obtain and optimize intended benefits (Brown et al., 2004; Morse, 2001). The conceptualization of strategic leveraging was a reflection of the need to move away from the impact studies which dominated the field of events at that time. These studies, besides often serving political expediency (Crompton, 2006), were focusing merely on impacts without explaining how and why these impacts occurred. Specifically, Chalip (2004, 2006) argued that although impact studies provided useful post hoc information, they were insufficient for event planning and management because they did not explain how these lessons would be applied and how the lessons from previous events could be readjusted to future events in different contexts. Even worse, the association of impact studies with the unfulfilled promises of high-profile events, such as the Olympics and the FIFA Football World Cup that did not deliver the expected well-advertised returns to the host regions (Burbank et al., 2001, 2002; Giatsis et al., 2004) obfuscated the complex landscape of their actual effects with suspicion. Skepticism and disbelief was (and still is) inextricably linked to the boosterism of mega-events’ political legitimizing rhetoric (Hiller, 2000; Waitt, 2001), leading inevitably to exaggerated benefits and underestimated costs (Hall and Hodges, 1996; Whitson and Horne, 2006). As such, there was a pressing need to develop sound analytical insight and know-how of the ways that event benefits could be produced (Bramwell, 1997; Jago et al., 2003; Ritchie, 2000).

Since 2004, a burgeoning literature on event leveraging has emerged, forming a new vibrant subfield primarily within the sport management discipline. Scholarship has also been gradually extended, beyond sport, to festivals and business events (e.g., Duignan et al., 2018; Foley et al., 2014). This demonstrates the robustness, versatility and pervasiveness of leveraging thinking to the different contexts that the wide variety of event types entails, ranging across genres, scales and purposes. At the same time, however, as the literature expands with the diffusion of leveraging ideas spreading throughout the event sector, this may complicate the development of a coherent common body of knowledge capable of maintaining and reinforcing the spectrum of its underlying and diversified strands of inquiry. Thus, it is important to bring together the rapidly growing lines of literature in order to identify emerging themes, cross-disciplinary trajectories and managerial priorities across the event sector, but also to delineate their interrelationships. In this vein, the osmosis of ideas and practices originating from the contexts of sport, cultural or business events can be more effectively enabled to cultivate and flourish event leveraging as a comprehensive interdisciplinary field of practice.

The concept of event leverage was defined by Chalip as “those activities which need to be undertaken around the event itself, and those which seek to maximize the long-term benefits from events” (2004, p. 228). This perspective constitutes an ex ante and strategic mindset focusing on a systematic analysis set to explain why and how intended outcomes can occur, thereby revealing the processes that can enable their attainment. Leveraging involves the formulation and implementation of event-themed actions, initiatives, campaigns and programs designed to achieve, magnify and sustain the outcomes of events beyond themselves. Thus, a leveraging lens views events as opportunities for interventions and not as interventions in themselves. It treats events as evolving assets that need to be leveraged in conjunction with the entire set of local resources and community assets. In other words, events and their opportunities are merely the seed capital; what hosts do with that capital is the key to obtaining intended benefits (O’Brien and Chalip, 2008). In this respect, the leveraging perspective provides an explanatory framework to theorize the municipal, provincial and federal governments’ efforts to activate the economic and social resources of hosting events to achieve public policy objectives (VanWynsberghe, 2015). For example, cities and regions can undertake leveraging initiatives to achieve urban regeneration, enhance destination branding, address social issues or increase sport participation. Policy purposes for leveraging vary across economic, social and environmental spheres depending on the context, conditions and needs of each host community, region or country.

As highlighted, the beginnings of event leveraging thought are traced in large-scale events and particularly the Olympic Games. Chalip (2002), in reviewing Australia’s leveraging strategies of the Sydney Olympics, encapsulated four core strategic components: (1) repositioning the country by capitalizing on media; (2) aggressively seeking convention business; (3) minimizing the diversion effect of the Games; and (4) promoting pre- and post-Games touring. As explained by Chalip, each strategy required a set of supporting tactics being implemented, such as creating programs for visiting journalists, Olympic media and sponsor relations, or starting campaigns promoting Australia as a meetings and convention destination as well as a place open for everyone to visit during the Olympic year, and putting together travel packages for pre- and post-Games touring. Chalip noted that the various leveraging initiatives undertaken in the Sydney Olympics generated new relationships and substantial learning on the part of those required to formulate or implement the associated strategies and tactics. However, in other types of events, as Chalip and Leyns (2002) showed in their study of the Gold Coast IndyCar race, the potentials for leveraging were largely unrealized due to stakeholders’ lack of capacity to identify events as leveraging opportunities, and ineffective coordination among local organizations.

Besides the Sydney Olympics, another notable mega-event case of leveraging is Manchester’s regeneration (Carlsen and Taylor, 2003; Jones and Stokes, 2003) and volunteering benefits (Downward and Ralston, 2006; Nichols and Ralston, 2012; Nichols et al., 2017) through the 2002 Commonwealth Games. This event was leveraged to achieve outcomes such as new Healthy Living Centers, extra-curricular activities for disadvantaged schoolchildren and more capacity to stage cultural festivals (Smith, 2014; Smith and Fox, 2007). Other mega-event examples discussed in the literature include the image leveraging of Germany using the 2006 FIFA World Cup (Grix, 2012) and the sustainability projects of the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympic Games (VanWynsberghe et al., 2012). Medium-sized and small-scale events have also been shown to bear potential for leverage. They can, for instance, consolidate local communities and improve residents’ quality of life (Ziakas and Costa, 2010a), build social capital (Schulenkorf et al., 2011), induce flow-on tourism (Taks et al., 2009), build a destination brand (Pereira et al., 2015), foster local trade (O’Brien, 2007), or sustain both commercial viability and community benefits (Schulenkorf et al., 2019). The juxtaposition of mega-events and all other types of smaller-scale events, which can be described as non-mega events (Taks et al., 2015a), brings to light their different magnitude capacity and resource requirements. Strategic leveraging can be applied to events of all types and scales, taking advantage of their respective capacities and characteristics. This necessitates that we rethink and readjust the fundamental logics and operational basis of event planning, management and evaluation.

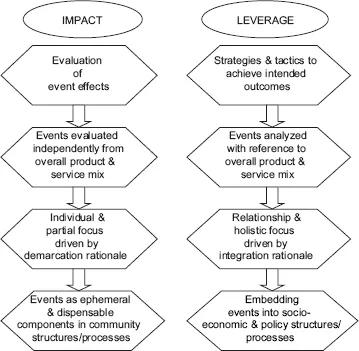

According to Chalip (2004), the study of event leverage refocuses event evaluation in a manner that is particularly useful for subsequent event bidding, planning and production. The underlying objective is to identify the strategies and tactics that can be implemented prior to, during, and after an event in order to generate particular outcomes. In this respect, the effects themselves are not important (as in impact studies), but are instead pertinent to the degree that they provide information about which particular strategies and tactics have been effective (Chalip, 2006). It is important here to distinguish the concepts of event impacts and leveraged outcomes. The impacts of events can be defined as their automatic effects (Smith, 2014) caused by a short-term impulse affecting directly the event environment such as local economy, resident well-being or facility construction (Preuss, 2007). Negative impacts can also occur such as increased prices for services, congestion, noise, crime and a tarnished destination brand (Jago et al., 2010). Leveraged outcomes are the positive results of strategic insight and implementation. Event leveraging, hence, represents a proactive approach to enhance positive impacts and prevent negative ones by setting up strategies for achieving well-defined short-term and long-term outcomes that make efficient and synergistic use of the host community’s assets (Chalip and Fairley, 2019).

Figure 1.1 illustrates the axiomatic mindset of event leveraging, as opposed to the impact rationale, to reveal the principal dimensions, parameters and implications that marked the paradigm shift from impact to leverage in event planning and management. As shown, rather than merely focusing on the individual and partial evaluation of demarcated event impacts, a systematic analysis of strategies and tactics for achieving strategic outcomes brings forward a relational focus in terms of fostering stakeholder collaboration, inter-industry linkages and cross-sectoral policy approaches that can bridge event leveraging with the broader context of the host community in which an event is embedded. This requires that events be analyzed with reference to the overall product and service mix in order to maximize opportunities for fully integrating them with their host community. Leveraging actions thus, should be tied to particular local features and capacities that extend beyond events and concern the whole impacted community and attendant range of stakeholders. In this vein, comprehensive targeted initiatives can be developed to meet policy objectives, address pressing community issues and optimize positive outcomes from events by capitalizing synergistically on a set of productive assets that deploy efficiently shared resources from the broad service delivery system of the host community. At its core, therefore, event leveraging has a holistic focus on cultivating relationships around events, which is driven by an integrative rationale that aims to embed events into their respective socio-economic and policy structures/ processes. Subsequently, events are not viewed as one-off ephemeral and dispensable components in community structures/processes, but as lasting and essential constituents with the potential to substantially contribute to sustainability. The next section outlines in detail the foundational premises that underpin the principal tenets of strategic event leveraging.

1.2 Foundational Premises

In general, leverage involves processes designed to maximize investments (Chalip, 2004). The term derives from the business realm, centered on long-term strategies through which corporations seek to achieve the highest return on their investments (VanWynsberghe et al., 2012). Its application to the event context means that events are seen as investments that require strategic intelligence. Simply put, leveraging concerns the strategic planning before, during and after the event. The matter is not just to achieve positive outcomes from events, but more importantly, to magnify and sustain them in the long-term. This epitomizes a diachronic perspective (pre-, during- and post-event) for enabling the optimization of benefits that lies at the core of event leveraging thinking. Accordingly, leveraging needs to be “an integral part of the decision-making process in the early stages of event planning” (Smith, 2014, p. 21) and bidding (Chalip, 2017). Thus, a grounding premise of event leveraging is temporal longevity encompassing the whole event lifecycle from conception to an extension of generating effects to the post-event period. In so doing, a subsequent premise underpinning the leveraging perspective is its strategic incorporation into broader development policies and initiatives (Chalip and Fairley, 2019). While, traditionally, events have been used on an ‘ad-hoc’ basis, the shift towards leveraging inescapably leads to a comprehensive integration of events into the public policy domain (Getz, 2009; Richards and Palmer, 2010; Smith, 2012; Ziakas, 2014a).

Fig. 1.1. Impact vs. leverage

Click to see the long description.

Smith (2014) makes the distinction between event-led and event-themed leveraging. Event-led leveraging entail initiatives closely linked to events, which attempt to expand the positive impacts of events. Event-themed leveraging comprises initiatives planned to capitalize on and maximize the opportunities derived from hosting an event. Thus, an event is used as a hook to obtain more benefits, which are not related directly to its hosting. The current event leveraging thinking emphasizes event-themed initiatives in order to extend the reach of events and benefit “a wider group of beneficiaries in a wider set of policy fields” (Smith, 2014, p. 27). Interestingly, event-themed leveraging has predominantly been applied to the context of individual large-scale sporting events, and not to portfolios of multiple periodic events as Chalip’s (2004) original model prescribed.

Actually, Chalip, in developing the foremost model of event leveraging (2004), envisaged a portfolio of events as a leverageable resource. This is because individual events, no matter their scale, are temporary opportunities and so their benefits are short-lived. It is, hence, highly problematic - if not unrealistic - to expect benefits to be magnified, optimized and sustained within the context of an individual event. To address this inherent limitation stemming from the very nature of events, a portfolio can be created assembling events of different type and scale to bestow their benefits through one another. To this end, it is necessary to cultivate synergies among the array of events, taking advantage of resource interdependencies and service offering complementarities. In line with the relational premises of event leveraging, a focus on event interrelationships is essential in order to enable effective cross-leverage among different events. Therefore, event leveraging is predicated on the concepts of event portfolio and associated cross-leverage that dictate the undertaking of joint and cross-promotional strategies. However, quite paradoxically the vast majority of emerging academic scholarship has continued to apply leveraging to the context of individual events. Perhaps disciplinary norms and agendas created an enduring mainstream comfort zone for studying individual events, out of which scholars are not encouraged to dedicate substantial research endeavor. Consequently, our knowledge on event portfolio leverage is embryonic and to a large extent hypothetical.

On the demand side, event leveraging encompasses a more comprehensive marketing approach targeting both core markets and complementary ones in order to optimize the reach of undertaken initiatives. This wide-ranging event consumer scope underlies a foundational premise of leveraging distinguishing three generic complementary markets: accompanying parties, incidental visitors and aversion consumers. Accompanying markets are the people traveling along with event aficionados, such as family and friends. In the case of amateur participation sport events, several members may accompany athletes, hence forming an entourage supporting sport event participants (Kennelly et al., 2019). Incidental markets are the casual visitors who happen by chance to be at the place an event occurs and might choose to attend (Weed, 2008). Aversion markets constitute prospective visitors who are however turned off by an event and might not visit the destination because of this reason (Ziakas, 2014a). Event leveraging extends its reach to all of these markets. It stipulates the formulation of tactics for augmenting event programs with ancillary events and activities that meet the needs of complementary markets and designing event spaces accordingly. In the case of aversion markets, the design of destined spaces to remain entirely untouched by an event’s theming, atmosphere and activities is intended to keep a destination attractive for visitors who do not enjoy the event.

Another basic premise of event leveraging is its antithesis, with the concept of legacy (e.g., Byers et al., 2020; Preuss, 2007, 2015; Rogerson, 2016; Thomson et al., 2019). Initially, event leveraging was seen as a way to achieve positive event legacies especially in the context of mega-events. While at first glance this seems to hold some truth practically speaking, it created confusion between leveraging thinking and the legacy planning framework primarily promoted by the IOC (International Olympic Committee), which put the onus of legacy on the organizing committee. From a leveraging standpoint, this is highly problematic as organizing committees are overloaded with the delivery of an event, and lack the resources or wider community connections and know-how, while most importantly, they are disbanded after the end of an event (Chalip, 2014, 2018). Thus, enough attention, considerable resources and concerted efforts cannot be effectively redirected from event organizing to its leveraging. In addition, leveraging diverts event managers away from their core purpose (Kelly and Fairley, 2018a). On the contrary, the establishment of a regional entity responsible for event leveraging is viewed as a focal constituent for specializing on this task, nurturing far-reaching stakeholder relationships and undertaking leveraging efforts in the long-run. Thus, event leveraging is substantially different from legacy planning. Conceptual clarity is required to avoid using these concepts interchangeably or confusing their meaning and implications for event management.

A regional entity with the role of fostering stakeholder relationships and forging alliances necessary for event leverage makes up a social structure for building local capacity for collective action. The value of collective action lies in getting people to act in concert to achieve common objectives, build community networks and cooperate to address issues or undertake joint problem-solving (Laumann and Pappi, 1976), especially since economic action is embedded within structures of social relations (Granovetter, 1973, 1985; Uzzi, 1996, 1997). The building of collective action and regional networks represents a cornerstone for event leveraging. There is strong evidence in the literature that event leverage may optimize obtained benefits through the establishment of a local entity and cultivation of regional inter-organizational relationships (Kelly and Fairley, 2018b; Werner et al., 2015a; Ziakas and Costa, 2010b). Initially, research focusing on the commercial development opportunities that events offer showed that strategic business leveraging requires the formation of inter-organizational rela...