- 138 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Northern Archaeological Textiles

About this book

This volume presents the papers from the seventh North-European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles (NESAT), held in Edinburgh in 1999. The themes covered demonstrate a variety of scholarship that will encourage anyone working in this important and stimulating area of archaeology. From the golden robes of a Roman burial, to the fashionable Viking in Denmark, through to the early modern period and more technological aspects of textile-research, these twenty-four papers (five of which are in German) provide a wealth of new information on the study of ancient textiles in northern Europe.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Gold Textiles from a Roman Burial at Munigua (Mulva, Seville)

Introduction

Of all the provinces into which the Romans divided the Iberian Peninsula, Baetica was doubtless the most appreciated for its richness in every sense and for the speed with which its inhabitants adapted themselves to the process of Romanisation (Thouvenot 1940; Padilla Monge 1989; Chic 1997); for this reason, it was the only one which became, under Augustus, a senatorial province. The strategic and economic attractions of this territory (especially the mining of metals) originated well before Roman times in a large number of indigenous settlements at a high cultural and economic level.

These indigenous peoples, Tartessian, Phoenician and Iberian (Bonsor 1899), were later to live alongside a series of colonies and municipalities of Roman making: we might draw attention, due to their proximity to Munigua, to those of Astigi (an Augustan colony), Urso (source of the famous lex Ursonensis), Hispalis and Corduba (Caesarian colonies), the Caesarian municipalities of Ilipa, Siarum and Italica (home of emperors Trajan and Hadrian), Carmo (a Julian municipality), Orippo, (today a suburb of Seville) and Irni (of the famous lex Irnitana (D’Ors 1986)). Thanks to the preserved fragments of the municipal laws of some of these small towns inscribed on enormous bronze sheets, we know much more about the municipal legal system common to the Roman Empire.

Munigua (Municipium Muniguense) belongs to the Flavian period (AD 68–96), although excavations show that in the Augustan period there was already an important indigenous settlement here. Alongside a few obviously Roman architectural elements (some walls), we have a clearly dated tessera hospitalis from this period (Nesselhauf 1960). The second century represented a period of greater economic development and civil construction, and in the third century the town became less active and was finally abandoned (Hauschild 1985, 255).

The aristocratic tomb of Munigua

The Munigua archaeological site was excavated for many years by the German Archaeological Institute of Madrid. Works were initiated in 1957 (Grünhagen, Hauschild 1979a). The tomb containing the fabrics was discovered in 1982 (Hauschild 1979). At present, Dr T Schattner has restarted excavations in the area (Schattner forthcoming) and has commissioned us to study the textiles. The totality of the findings will be the subject of an exhaustive publication on which a large team of experts will collaborate.

The capitol of Munigua consists of a temple-sanctuary which is of the same architectural type as that of Fortuna in Praeneste. It is therefore a kind of revival built two centuries later in the era of Vespasian. Dedications to Hercules, Fortuna and Dis Pater and the names of important families are frequent in the inscriptions.

There are two small burial grounds in the city area (the eastern and western necropolis) and, connected to the eastern necropolis, a mausoleum of the second century with four openings in the stone floor for cinerary urns. Our tomb, of the bustum type (pyre and fire) without any overlying architectural structure, was discovered directly in front of the mausoleum, on the last day of the 1982 excavations (Blech, Hauschild, Hertel 1993, 9). This meant that Dr Hauschild felt obliged to make a drastic decision. He had to choose between leaving it in the ground until the next dig (knowing that everywhere lay small pieces of gold textile) or collecting it all as carefully as possible. He went for the second option and, the burial being fairly superficial, he divided up the entire area into twenty-six rectangular sections. Each piece of the burial was made up into a bundle reinforced with cloth and plaster. Only later was a textile restorer from the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum of Mainz called for consultation, but was unable to get the materials X-rayed. The humidity and acidity of the earth have caused much deterioration inside the bundles of iron, bones, wood and glass.

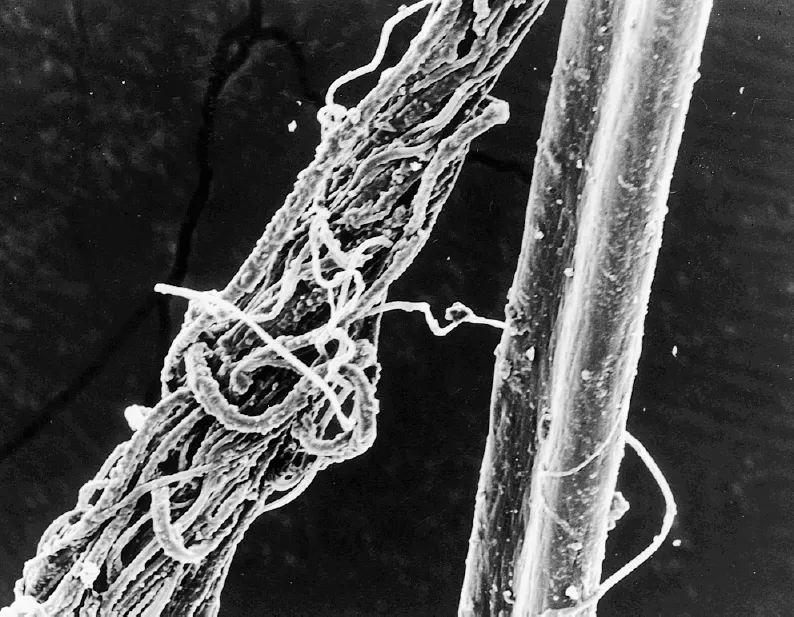

Fig. 1.1 Scanning electron micrograph of a silk fibre (right-hand image) from Munigua (photo. Carmen Alfaro Giner)

In 1998 a systematic excavation of each of the bundles began in the museum laboratories. To date nos 16 to 19, 1, 8, 8a, 12 and 21 have been studied. The first two showed the largest amounts of gold textile and twisted cord. Fragments of iron, bronze, small nails and little bits of bone were found in nos 18 and 19. No 21 had a fragment of cylindrical ivory (5mm in diameter, 13cm long) which may have formed part of a small spindle of a kind common in this territory. In the Seville Archaeological Museum there is a significant and very well preserved small collection of Roman spindles, shortly to be published in Archaeological Textiles Newsletter.

The jewellery and ornaments which have appeared so far (some necklaces and a bracelet) seem to suggest that a woman was buried here. The analyses of the few bones recently found will surely confirm this. The large accumulation of long iron bars and bronze elements which could be the legs of some piece of furniture suggests that all this may constitute a funerary iron bed on which the richly dressed corpse was placed (Blech, Hauschild, Hertel 1993, 9).

The textile remains

What is of interest to us is the textile activity which can be linked to this region, especially to Munigua. In fact Munigua has provided us with small but very interesting fragments of material which can help us to understand better ancient textiles and their probable distribution through trade. They represent a technical innovation in the Hispanic region, as they are the first gold textile remains to be found there, with the exception of the Roman ornamental netting from Medina Sidonia, Cádiz (Alfaro Giner 1983–84). Our present paper will focus on tiny pieces of rich fabric which may have been parts of ornamental braiding or trimmings.

To date, we have no information as to whether there were remains of other fabrics in the burial, for example linen. In the present case the gold may have consisted of a simple sewn braid for exclusively ornamental purposes. Luckily the high quality material on which we are reporting has remained almost intact over time, namely gold, as yet not analysed, and what seem like short silk filaments of white, blue and vermillion red. Unfortunately the fragments of cloth or braid are very small and the fibres are barely visible to the human eye, but we are looking at remarkable wealth in the funerary dress of the deceased.

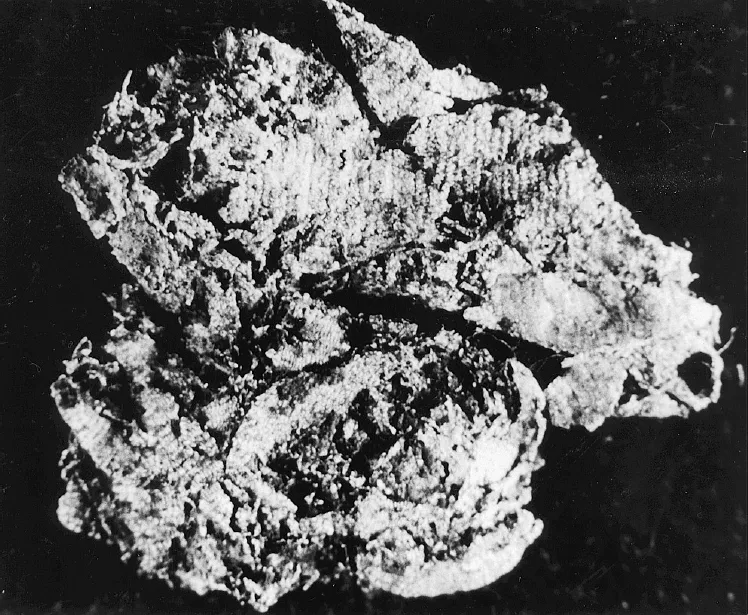

Fig. 1.2 Scanning electron micrograph of cotton fibres from Munigua (photo. Carmen Alfaro Giner)

The colour of the fibres seen under a microscope or a binocular magnifier was so brilliant that at first we believed them to have come from the clothing of the people who made up the bundles or from the restorers who recently excavated them in the laboratory. But soon we realized that, in totally aseptic conditions, these tiny coloured fibres kept on appearing deep inside the earth of the packets and stuck fast to the gold remains. Photographs obtained with the scanning electron microscope (SEM) revealed clearly that some actually came from the hollow sections of the gold threads. Occasionally the fibres showed the double structure typical of silk (Fig. 1.1), with a diameter of 9μm. (This value comes within the category which Pfister considered usual in the soie véritable of the textiles of Palmyra (1934, 45) in which ‘la fibre mesure de 6 à 12mm sur la même fibre, exceptionellement 15mm’). In other photographs we seem to be looking at cotton fibres (Fig. 1.2). As comparatively little material has been studied, a more definitive analysis is needed to determine their exact composition. At any rate the colours of the fibres are of intense brightness and we are attempting to separate the white, blue and red fibres into three groups with the aim of analysing the dyes later.

The high temperatures reached in the funeral pyre caused the fibrous cores to disappear and the gold threads to begin to melt together. This occasionally gave the material a crushed or wrinkled appearance. A large part of it was lost in this way, as well as the hypothetical base fabric on to which we think the precious materials were either sewn or woven. As the bustum cooled down, the gold threads, now hollow, solidified, creating the small compact surfaces illustrated in Fig. 1.3. However, in some of the pieces the structure of the fabric is well preserved (Fig. 1.4). It consists of a plain tabby weave (1/1), with tight Z-twist threads along the weft, the warp threads no longer existing. Presumably, if they were of animal or vegetable fibre, the fire destroyed them. The gold threads were composed of a fibre core with a ribbon of gold spiralled around it. The thin gold strips are approximately 0.2mm wide, twisted on a 0.1mm diameter thread. There are 10 threads per mm of weft, that is to say 100 threads per centimeter.

Fig. 1.3 Scanning electron micrograph of gold fabric from Munigua, its surface partly distorted by heat (photo. Carmen Alfaro Giner)

Fig. 1.4 Scanning electron micrograph of gold (weft) threads from Munigua. The yarn is now missing (photo. Carmen Alfaro Giner)

For now we are unable to comment on the form or pattern of the material as a whole. The gold fragments appear in the earth in no particular order which might help us to understand this. However, it is sometimes possible to observe in many of them a rhomboidal form (Fig. 1.5). If this form follows a particular design, it is as yet impossible to demonstrate it. We must wait for the excavation of the bundles to be completed to give more information in this respect.

Fig. 1.5 Small fragments of the gold fabric from Munigua adhering to one another (photo. Carmen Alfaro Giner)

Fig. 1.6 Twisted cords of gold from Munigua. The longest is 2.7cm. (photo. Carmen Alfaro Giner)

Along with large quantities of this kind of textile, which always consists of very small fragments, twisted cords of gold are also frequent (Fig. 1.6). Those visible in the photograph are composed of two 0.6mm diameter cords in a Z-twist, each consisting of fifteen to eighteen 0.1mm threads in a Z-twist. These combine in an S-twist to form a cord 1mm thick and 27mm long. The function of these small gold cords in connection with the fabric is as yet unknown, but their form might suggest the presence of some kind of fringe.

Epilogue

As we know, fabrics made with gold thread were already in use during the Hellenistic period: finds have been made at Vergina, Macedonia (Andronikos 1984, 191–195) and Kertch in the Crimea (third century BC) (Stephani apud Pfister 1934, 23). Nevertheless there have been more finds in burials of the late Republican and Imperial Roman periods, from the first century BC to the fourth and fifth centuries AD, by which time their use had become relatively common (Wild 1970). The best preserved were those found in arid regions like Palmyra (Pfister 1934, 17, 18, 45, 54, pl.I, IVb, XIIa; 1937, 11–12; 1940, 16, pl.III) or Dura-Europos in Syria (Pfister, Bellinger 1945, 60), all of these prior to the last quarter of the third century AD. We have precise descriptions that distinguish between the mince lamelle d’or battu, of an average width of 0.3mm., and the much more fragile membrane org...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations for NESAT Volumes

- Chapter 1: Gold Textiles from a Roman Burial at Munigua (Mulva, Seville)

- Chapter 2: Two Gallo-Roman Graves Recently Found in Naintré (Vienne, France)

- Chapter 3: Das Mädchengrab der Fallward: Vorläufiger Bericht

- Chapter 4: Frühmittelalterliche Textilien aus der Nordostschweiz

- Chapter 5: Textile Pseudomorphs from a Merovingian Burial Ground at Harmignies, Belgium

- Chapter 6: Denmark – Europe: Dress and Fashion in Denmark’s Viking Age

- Chapter 7: Brocaded Tablet-Woven Bands: Same Appearance, Different Weaving Technique, Hørning, Hvilehøj and Mammen

- Chapter 8: Textile Production at Birka: Household Needs or Organised Workshops?

- Chapter 9: Who Produced the Textiles? Changing Gender Roles in Late Saxon Textile Production: the Archaeological and Documentary Evidence

- Chapter 10: Handwerk oder Industrie? Erfahrungen bei der Herstellung eines hochmittelalterlichen Wollgewebes auf dem Gewichtswebstuhl

- Chapter 11: Textiles of Seafaring: an Introduction to an Interdisciplinary Research Project

- Chapter 12: What Makes a Viking Sail?

- Chapter 13: Textiles for Transport

- Chapter 14: The Greenlandic Vaðmál

- Chapter 15: Stand und Notwendigkeit der Forschungen über die mittelalterliche Wollweberei auf dem südlichen Ostseegebiet

- Chapter 16: The Collection of Archaeological Textiles at Prague Castle

- Chapter 17: Textilfunde aus dem dreizehnten bis siebzehnten Jahrhundert: Neue Funde – Neue Erkenntnisse

- Chapter 18: Sixteenth-Century Textiles from Two Sites in Groningen, The Netherlands

- Chapter 19: ‘The Apparel oft Proclaims the Man’: Late Sixteenth- and Early Seventeenth-Century Textiles from Bridge Street Upper, Dublin

- Chapter 20: Women’s Robes Excavated from the Burial Crypt in the Holy Virgin Mary’s Church, Toruń, Poland

- Chapter 21: The Influence of West European Fashion on the Clothing of Toruń’s Townsfolk

- Chapter 22: The Human Development of Different Fleece-Types in Sheep and Its Association with the Development of Textile Crafts

- Chapter 23: A Preliminary Classification of Shapes of Loomweights

- Chapter 24: Remarks Concerning Some Details of Early Spinning Wheels

- Addresses of Speakers

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Northern Archaeological Textiles by Frances Pritchard, John Peter Wild, John Peter Wild in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.