- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

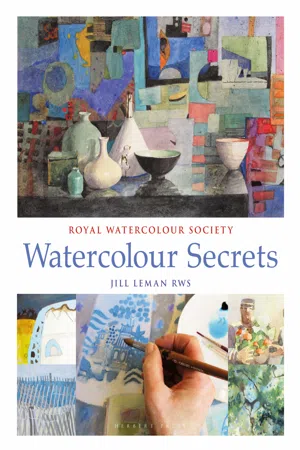

Watercolour Secrets

About this book

A beautiful survey of the work of the members of the internationally respected Royal Watercolour Society, representing the finest contemporary watercolour painting in Britain today.

This stunning book showcases the work of the members of the prestigious Royal Watercolour Society, including Ken Howard, Sonia Lawson and many other fine and well-known contemporary watercolour painters. Each artist discusses their inspiration and gives their best practical advice for working in this medium, offering a fascinating insight into the methods and techniques of professional artists.

Have you ever wondered how an artist starts a piece, what keeps them working at it, how they make marks and mix colour or when they know a painting is finished? This intimate exploration of the daily creative striving of the artist and their patient technical procedures will fascinate professional and aspiring artists, collectors and anyone with a general interest in painting.

This stunning book showcases the work of the members of the prestigious Royal Watercolour Society, including Ken Howard, Sonia Lawson and many other fine and well-known contemporary watercolour painters. Each artist discusses their inspiration and gives their best practical advice for working in this medium, offering a fascinating insight into the methods and techniques of professional artists.

Have you ever wondered how an artist starts a piece, what keeps them working at it, how they make marks and mix colour or when they know a painting is finished? This intimate exploration of the daily creative striving of the artist and their patient technical procedures will fascinate professional and aspiring artists, collectors and anyone with a general interest in painting.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Diana Armfield

What gives me that urge to draw or paint? I think any experience in our family life that I have enjoyed, loved or admired, that I can interpret visually. Much that we took for granted is threatened and needs to be cherished and honoured. I want to hold on to these experiences and share them with others. I am thinking of land, sea and peopled townscapes, flowers and places where people gather to be convivial; long lunches, picnics, galleries, concert halls and cathedrals, to mention just a few. I have found that no matter how I arrive at my subject, the act of interpreting in paint or drawing makes it significant; that particular view, whether it is just a pencil outline of a mountain slope or a well-considered watercolour, will always mean more to me than it did before.

Lambing Time watercolour, gouache & pastel 16 x 21.5cm

Conversation in Piazza Navona, Rome watercolour, gouache & pastel 24 x 16cm

Some experiences are turned into paint directly, others, now we are in our nineties, are from memories of painting trips abroad, sparked off from old sketchbooks. Watercolour and gouache seem to lend themselves to these memory images, but so also do present-day Welsh landscapes with sheep!

I have accumulated watercolour paper over the years, of many different kinds, and the differing surfaces have a marked influence on the outcome, either helping or frustrating my efforts. I like a paper that is heavy enough not to need stretching, one that takes the initial drawing sweetly.

I often set out with the intention of keeping the drawing very simple, just there to guide my watercolour, but another sequence can easily happen instead. I become so absorbed by the drawing that it evolves into something too dark and complex for the watercolour to properly take over. I turn to gouache, which can dominate, and the work then develops into something richer, but I’ve lost my watercolour with it and perhaps a little of the luminosity.

Next to me on the drawing table is the big open box of pastels and before long I’m reaching out for a stick of pastel to breathe light into the gouache; the work has taken on a new aspect. The original elements are there but the language has changed. It may well turn again if I’m not satisfied, back to gouache, or even under the tap to be started again with watercolour over a mere shadow.

I began with a career designing fabrics and wallpaper, which alerted me to the rhythms and patterns in nature. I was turned to painting by circumstances of teaching drawing for painting at The Byam Shaw Art School, and never looked back. I had always admired the touch in paint of my husband, Bernard Dunstan. The handwriting of his painting revealed so much about himself and his subject, and still does. I was thrilled to find myself working in a medium that seemed to demand the development of handwriting. This might be both conscious and unconscious, but is inevitably personal and the very brushstroke of which it is made has to have an abstract life of its own, contributing to the build of meaningful shapes.

What I aim at in all my work stems back to childhood. My mother created, from four acres of untouched difficult gravel and sand soil, a garden, areas of field, flowers, grass-scrub and orchard that to me were a completely satisfying world. I think I absorbed unconsciously the principles by which that garden matured into something so deeply fulfilling. It is those principles that I hope underlie my work. There were linked divisions made by yew, lime and oak making a stable framework. Against this almost formal design played a waywardness from the things that grew; vistas, secret places, surprises and mysterious corners, all together making a welcoming background for people and animals.

When I am composing from drawings or looking for the composition on the spot, I have these principles of contract and contradiction in the not-so-back of my mind. I want to give the spectator enough clues to read the work, but hide enough to be revealed later. I want to find the geometry in the scene, have it there in the work, but break into or disguise it. In fact, one might say that for every solid statement of tone, shape or colour, I’ll look for something counter. Of course I am overstating this. A lot of painting is following what is on offer and trying to get it right! There again is a contradiction which is part of the magical, difficult medium of watercolour.

Fay Ballard

My training took several paths: the City Lit taught me to draw and paint from observation and from the imagination and its Foundation Diploma covered painting, printmaking, video, sculpture, textiles and drawing as well as technical skills such as colour theory and perspective. At the Chelsea Physic Garden, the Diploma in Botanical Painting enabled me to specialise in drawing and painting plants from life. We spent days learning to control the flow of watercolour paint with our sable brushes, and attempting to draw a leaf accurately. There were many false starts, setbacks and disappointments but slowly, it all started to come together.

Radiccio 2011 watercolour 30 x 30cm

Family 2006 watercolour 132 x 96cm

Leaves 2011 watercolour 45 x 37cm

The most valuable part of my MA in Fine Art at Central St Martin’s Art School was the emphasis placed on theory and ideas. We were encouraged to keep a journal recording our thoughts, influences, inspirations, and things we liked or disliked. Every so often, I would draw a mind-map of my ideas, and when I look back over these journals now, I can see the key threads running through them. We presented work to our peer group regularly, and although daunting and adversarial, this was a useful exercise to help clarify thoughts, or resolve problems. Today, I write in my journal, keep an A4 sketchbook to rough out ideas, and rely on friends to give honest feedback.

After completing my training in 2006, I became absorbed making plant portraits from observation, as a vehicle for exploring my unconscious emotions. I was interested in the numinous, and friends often remarked that my work had an uncanny quality, as if the plants were alive or charged. I was reading Freud’s theories on the uncanny as well as Rudolf Otto’s book The Idea of the Holy and Kant’s essay on the sublime. Dürer and Edward Burra were inspirations.

Dedication and perseverance are vital, but so, too, is luck. I was fortunate to be invited, along with others, to paint the plants at Highgrove for HRH the Prince of Wales who wanted to create a florilegium under the auspices of the Prince’s Foundation. A series of exhibitions and a publication followed, which presented the opportunity to see the variety of responses to the project from artists throughout the world. The early support of Dr Shirley Sherwood, the pre-eminent collector of botanical art, has also been invaluable, enabling me to exhibit in several countries.

My working method involves finding suitable specimens, making rough drawings, and finally, a delicate outline pencil drawing (HB or B sharp pencil) on stretched hot-pressed Arches or Fabriano paper (300gms). A faint tea-wash is applied over the drawing, then the lights and darks are modelled, and detail added. Sometimes, I blot out colour with a paper towel to achieve highlights. I use fine-pointed sable brushes (Series 7, Kolinsky Winsor & Newton sizes 4 to 6). I prefer a restricted palette and semi-translucent colours: French Ultramarine, Schmincke Lemon Yellow or Winsor Yellow, Magenta, Raw Sienna and Burnt Sienna. I work on a table in my...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Artists:

- Contributors to Watercolour Secrets

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Watercolour Secrets by Jill Leman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.