- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

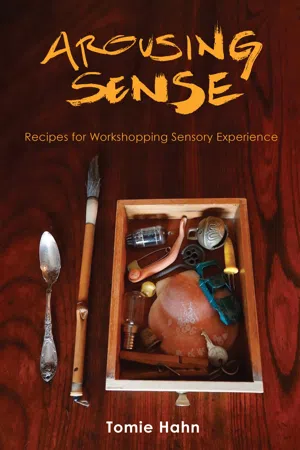

Engaging with sensory experience provides a gateway to the contemplation and cultivation of creativity and ideas. Tomie Hahn's workshopping recipes encourage us to incorporate sensory-rich experiences into our research, creative processes, and understanding of people. The exercises recognize that playfulness allows for a loosening of self while increasing empathy and vulnerability. Their ability to spark sensory endeavors that reach into our deepest core offers potentially profound impacts on art making, research, ethnographic fieldwork, contemplation, philosophical or personal introspections, and many other activities. Designed to be flexible, these living recipes provide an avenue for performative adventures that invite us to improvise in ways suited to our own purposes or settings. Leaders and practitioners enjoy limitless arenas for using the senses for explorations that range from personally transformative to professionally productive to profoundly moving.

User-friendly and practical, Arousing Sense is a guide to how teaching through sensory experience can lead to positive, transformative impact in the classroom and everyday life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Arousing Sense by Tomie Hahn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

IMPULSES

Try this appetizer:Smile so deeply and strongly that your eyes close.Hear and feel anything?As you release, notice what stirs in your awareness.

I begin with an impulse, to arouse sense. Even small impulses can stir a wave of excitation, signaling vibration and energy. Embodied poetry. Noticing the stimulus, and any changes in your realm of sensational knowledge, is entirely up to you. Over time, with practice, we notice more. I seek to know how we might teach/learn sense.

Arousing Sense is a simple book of experimental “recipes” for engaging sensory experience. It is for everyone. No specialization needed. Attendance to the vast array of sense can flatten disciplinary boundaries. The purpose of the workshop recipes is to stimulate creative activity by engaging with our senses and to heighten sensory awareness in order to deepen our understanding of what it is like to be human, to be you. Because there is an endless sea of sensory information that we are immersed in, noticing what you are aware of (and what is filtered) reveals and situates your reality, your sensibility. The recipes support workshop leaders and solo practitioners with straightforward instructions for sensory exploration. Being aware of what we sense is the first challenge; using that embodied knowledge to express it is the second. I present several large-scale challenges in this book: how can we expand our modes of expression while heightening awareness? Words are powerful. Before words change our lives, can we allow ourselves to reside in the moment of experience and let the encounter drive the change, sensibly?

Let’s awaken, by aspiring to explore, flex, and heighten sensory awareness. Sensory modalities express (manifest) energy and existence differently over time. Can we notice the nuances, then express (convey) what we notice? If we consider that we inhabit different sensory worlds—personally and culturally—then building awareness of the sensibilities someone else might be experiencing can expand our knowledge of self/other and open communications. Some sensibilities may be intrinsically subtle, or outside of our own experience, so that we are unaware of them. Deepening awareness, sensational knowledge, supports empathy and encourages compassion. The consciousness starts with the smallest of impulses. Shifting one’s sensory point of view, being open, shedding assumptions, and inviting empathy and vulnerability into our explorations can enable deep revelations that what we experience may not be the same as what others experience. Beyond that, how we interpret and respond expressively to experiences can help us to expand, imagine, and notice how we orient ourselves in the moment.

Arousing Sense directs attention to embodied knowledge for exploring the realm of creativity and knowledge making. The recipes are practiced-based explorations and discussions meant to arouse the senses and to “make sense” of how sensory experiences help us to orient ourselves in our environments over time. Let us also ponder what sensory information might be absent, overlooked, or overshadowed because other sensory modalities mask its presence or because of our lack of awareness or sensitivity.

Fostering Transformation

At such a crucial time in history—when contemplative studies and arts, practice-based and praxis-based pedagogy, multiracial pedagogy, feminist pedagogy, communication and intergroup dialogue, intercultural practices, politics of race, critical pedagogy, trauma studies, engaged pedagogy, sensory studies, and student-centered learning (to name only a few!) have been emerging—I hunger for new possibilities to collaboratively address the harsh political climate and social conflicts. (A sampling of influential books includes those by Ahmed [2012]; hooks [1994]; Freire [2007]; Ergas [2017]; Gershon [2011]; Howes [2005]; Pennebaker and Evans [2014]; Rechtschaffen [2014]; Thompson [2017]; Barbezat and Bush [2014]; Smith [2012]; and Stoller [1989, 1997].) Years ago, I yearned to move these revolutionary theories into the classroom. However, while I held many of these radical, groundbreaking theoretical foundations in my storehouse, I realized I had little substance—actual in-class teaching examples—to arouse sense in the classroom. I needed to create engaging lesson plans to address even the basic groundwork of communication, of sensibilities. For example, how do we engineer vibrant presence in class or workshop settings? Safe discussions that shed light on bias? How can students and teachers, together, find a sense of well-being that fosters transformation? How can we note challenges of difference and propose moving through them together in “radical vulnerability” (Nagar 2019)? How do we create safe, accountable spaces that also offer playful qualities that stir up new experiences and ideas to move everyone to their own edge of vulnerability so growth can flourish? How can we spark inquisitiveness, curiosity, and creativity alongside emotional well-being? Most importantly, how do we bring the experience of the lived body into the classroom, into research, into our creative work and our writing? How can we challenge what ethnography, art, and creativity is? (See Elliot and Culhane 2017.) The recipes in Arousing Sense are meant to engage embodied practices to observe how we think with the body. Many recipes in the book develop a sense of community by cultivating shared experiences—“shared,” yet again, everyone quickly notices how differently we each experience the world. As Ahmed claims that “to account for racism is to offer a different account of the world” (2012, 3), I offer that bias and assumptions of difference often spark from the smallest of impulses and the interpretations of our sensory experiences.

I want to acknowledge that there are ample resources for creative teaching practices for embodied knowledge from yoga, martial arts, okeikogoto (Japanese practice arts), contemplative arts, and other practice communities. The sensitivity of bringing some practices into the classroom can be challenging, due to the implied or very real spiritual nature of some. Note that I do not use the term “mindfulness,” not because I am opposed to it but because the word is quite loaded. The popularization of meditation and “mindfulness” has shifted the meaning for some communities, sometimes for positive results. But I would like to be clear that when I run classes or workshops, the point of the exercises is to heighten sensory awareness. Personally, I find the observation of sensory information in time to be profoundly contemplative, yet I reserve this as my own experience and do not impose it on others. When conducting workshops in particular communities focused on contemplative practice, of course my vocabulary changes.

Long ago I discovered that I derive great pleasure from creating prompts and offering them as experimental sensory challenges for others or for my own personal workflow. My childhood was an odd combination of strict discipline in traditional arts juxtaposed with fiercely experimental encounters. Imagine living inside or as a Dada piece, a Fluxus event, a happening, a pop art scene, or a Zen koan. Welcome to my childhood. My parents, both visual artists with a passion for experimenting and teaching, created a wild, if not bizarre, home life that surely fostered my interest in creating prompts. Fold in my complicated biracial existence (Japanese and German American), one that continues to develop and settle. Elsewhere, I have written about being biracial and how my mixed perspective encouraged and afforded but also blinded me to various insights in my creative, ethnographic work (Hahn and Bahn 2002; Hahn 2007), so I will not detail it here. My family lived on a cliff with fifty-two natural stone stairs leading to our tiny house. Looking back, I recognize that the unusually insular, creative environment atop this cliff stimulated a heightened gaze and sensitivity.

Decades later, my fascination with the transmission of embodied cultural knowledge via the senses, mixed with an upbringing in okeikogoto, meditation, dance, experimental improvisation, visual arts, and later Deep Listening, contributed to these recipes and how I teach.

The Importance of Time

Awareness of changes in sensory qualities over time magnifies presence. What sensory changes we perceive and notice directly affects us and our environment but also our perspective of the world—witnessing difference; noting hegemonic structures; sensing climate changes (Silvers 2018); recognizing the situatedness of our lives and relations to others and things; and observing nuances of presence. Recognizing changes allows us to be sensitive to others, to pause, and to consider how to respond and interact. I cannot emphasize enough how strongly the impact of heightened awareness can be on self-awareness, communication, and the sense of connectedness to others and our environment.

Attending to sensory experience pulls us into a contemplation of time, the moment, now. We can notice the state of our personal life and our environment, both local and global. If we are actually focused on encounters demanding heightened awareness, the experience requires that we consider the sensory changes unfurling in time.

As an example, try this:

Directly after reading this sentence, hold your palms against your ears, close your eyes and breathe in and out slowly, and note as many sensory details as possible. (Pause here.)

Although brief, such a pause in one’s day can summon a deeper understanding of time, sense, and being. But note, your palms-over-ears moment is your particular experience. It emanates from a situated moment and space, including the complexity of who you are, where you are right now, your associations with the activity, and most importantly the particulars and details of the sensory moment—the shape and feel of your hands, head, and ears; how you cupped your ears; the blood flow in your fingers; your breathing and awareness. These intimate qualities, and especially what you noted about the experience (or if you continued reading, not pausing to enact the mini experiential experiment), reveal much about you and how you are at this moment in time.

The nuance of sensory encounters throughout our day, if we allow ourselves to be present to them, can provide profound transformations. Considering the potentials for growth through sensational knowledge inspired me to create, research, perform, and teach differently. How might we immerse ourselves in sensory experience and allow the encounter to be unique, to wrestle with language, and in doing so find other means for displaying the nature of what we experience? Seeking alternative means for displaying knowledge has always presented creative challenges for me.

As an explorer of sense, I offer these recipes as performative experiments.

2

MAKING SENSE

In the following passage from my fieldnotes I muse about a voyage to Machias Seal Island Wildlife Refuge, approximately twenty miles off the coast of Maine, to stand inside of a 3′ × 7′ wooden box for the privilege of observing puffins in their natural habitat. Strictly, only a certain number of people are allowed to venture onto the refuge each day.

Expanded fieldnotes. Machias Seal Island Wildlife Refuge, Maine, July 16, 2019. The day began around 6 A.M. in Cutler Harbor, boarding a small boat in two trips to take the group of eighteen to a larger boat, then over an hour voyage out to Seal Island. Luckily, the weather brought no surprises. Although it is mid-July, wearing layers of clothes is important because the trip via boat would be chilly and windy. The seascape offered a wealth of dramatic sensory delights and challenges—sea lions, bald eagles, whales, dolphins, with sun, wind, and salty water whipping our faces, and lapping the boat—but here I’ll focus on the blind destination. We’d planned for over six months to be squeezed into the blinds for ninety minutes. “Blind”—what a funny word! Yes, inside the box we were detected less by the outside world, but the sights, sounds, smells, orientation, movements, and general feel inside the dim blind aroused keen new experiences as well.Once we landed on the island the naturalists recommended carrying a thin dowel pointed upward over our heads while traversing designated paths. We would quickly note how the highest point (hopefully the dowel tip) endured confrontational pecks from various sea birds, who apparently interpreted our presence as hostile. The naturalists pointed out specific locations where our presence would cause disruption to active nesting. During our visit, for example, terns occupied and fiercely protected their nest on the outhouse roof. After our outhouse visits, the naturalists instructed us to dutifully walk only on designated pathways to the blinds with no stopping for photographs or loitering along the route to minimize bird nesting disruptions. Four of us would occupy our small blind. Once we entered, we would have ninety uninterrupted minutes to observe the surroundings. However, to minimize perturbing puffin habitats, an early exit from the blind meant no reentry. I focused and gingerly walked along the path to the blind, resolved not to be distracted by any alluring puffin commotion. Already our visit posed an abundance of sensory drama.The wooden blind intrigued me. Painted dull grey, the exterior attempts to camouflage the rectangular box and its human inhabitants among the grey boulders. Although merely constructed from basic pressboard and 2″ × 4″ lumber, the bare, natural wood interior felt warm and rustic. A simple sliding shutter allowed inhabitants to peer out from a number of different views, but we were instructed to keep window shutters closed unless in use. The distinct sensory atmosphere inside the blind emanated from a tangible feature, its repeated use. I noticed the wood was smooth yet also worn below each window—remnants of inhabitants leaning for hours on the wood leaving residual body oils and indentations from heavy cameras or binoculars resting on windowsills. The blind itself embodied the layered presence of its many visitors over the years.In the blind, a variety of sea birds surrounded us. Literally. Atlantic puffins, as well as razorback auks, landed on the blind roof to congregate, webbed feet creating sharp percussive slapping sounds alternating with a muffled shuffling noise, perhaps from waddling feet. Groups of puffins congregated on top of large boulders just outside the blind, while others peeked out from crevices between boulders as if they had their own sheltering blinds. Often nesting takes place below boulders, and I noticed high traffic and well-guarded areas near such mini caves. The sunny day, enhanced by the brilliant reflection of sunlight from the ocean, green plants, white rocks speckled with yellow-orange lichen, and white excrement, presented a vivid backdrop for viewing sea birds. Despite their small stature, puffin characters loom large. They display white feathers on their torso and black wing feathers. Their comically large bill with bright orange stripes, large eyes, and orange feet contribute to the distinct puffin c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Menu

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Author’s Note

- 1 Impulses

- 2 Making Sense

- 3 How to Use This Book—A Quick Review

- 4 Tantalizing Recipes

- 5 On the Go

- 6 Dessert

- 7 Resources

- 8 Cordial Closure

- References

- Index

- Back Cover