- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

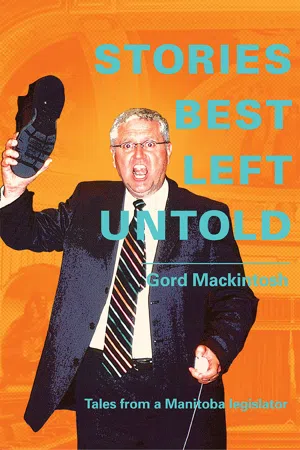

Gord Mackintosh was not your typical politician and this book is not your typical political memoir. Mackintosh steps out of his familiar role as the Manitoba NDP's go-to guy, foot soldier and law reformer to provide a unique take on the quirky places and people behind his long and varied career. From secret passages, archaisms, and funny business at Manitoba's Legislature, to door-knocking surprises, crime-fighting and "saving Mother Earth," Mackintosh weaves warm-hearted anecdotes of his many years in public life. Hooey, hijinks, and embarrassment that humanize our political system are interspersed with major political events of the last thirty years, for which he had suspiciously differing roles. Whether Manitoba's French Language Crisis, the Meech Lake Crisis, the MTS Debate, the Flood of the Century, the Auto Theft Capital of North America, or the internal rebellion against Premier Greg Selinger, he still urges, "It wasn't me." Calling it "more sunshine sketches than social science", Mackintosh exposes what it's really like in politics, with seasoned political advice, strong opinion -- including an "unbiased view" of opponents, and a celebration of leadership. He also offers a self-deprecating backstory to many government decisions—required reading for Manitoba citizens of any political stripe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stories Best Left Untold by Gordon Mackintosh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Political BiographiesPart I

But First I Was Born

Here comes mischief … and good legislation

1

My Fort

The envy of kids with a dad – my fort in the Fort

Surprising to some, I’m from my hometown.

I was born and raised in Fort Frances, Ontario, or “the Fort,” the greatest place of its kind, on the biggest lake of its size, with the longest bridge of its length. The Fort is located smack dab, right there where it is. Outdoor types know it’s where the waters are wet and the forests are wood. It’s the fishiest. The gamiest. To ward off an influx, I use that line, “You can’t get there from here.”

The Fort was a big place in my young eyes. It offered great memories and lessons – both enduring and endearing. I brag that, like other hubs, the Fort’s transportation network includes a subway; we’ve always called it that, where Portage Avenue goes under the railway. When the town built its first overpass across that busy railway to the east, drivers stopped on top for the view.

The Fort taught me you have to promote what you’re proud of. There’s an apartment building. It’s three stories high. It has an elevator. It’s called “Shevlin Towers.” Not to be outdone, there’s the two-storey “Sky View Apartments” downtown.

I moved four hours down the highway to Winnipeg in the 1970s, but the Fort remains special. Dad died when I was two and I feel the community chipped in to help raise me, along with my Mom, Gramma Mack, older sisters Charlotte and Elizabeth, and The Andy Griffith Show. It does take a village to raise an MLA.

Dad was from a town in northern Scotland called Helmsdale in the parish of Kildonan. He was named “Gordon” for his fish curer-enterprising grandfather who died upstairs in the family home on the North Sea the day Dad was born downstairs. Dad immigrated to Winnipeg with his parents in the early 1900s. Scots came to Winnipeg as “Selkirk Settlers” from the same parish a century earlier so Winnipeg was known to highlanders. And that was before discount outlets.

The McIntosh family, as they spelled the name, settled in booming St. James where Dad’s father built homes before moving downtown to Vaughan Street and then to Selkirk where he taught trades to support their family of six. Dad was hard-working and determined. He got what was then a plum, white-collar job as a Winnipeg bank teller at Selkirk Avenue and Main Street. We still have the brass pot he selflessly bought Gramma with his first paycheque. He attracted the attention of a bank inspector, Art Chipman, who recruited him to become a collection manager for his finance company. But Dad took ill with aggressive TB. At age twenty-two, with great suffering he began almost ten years of fresh air and rest at the Ninette Sanatorium. Gramma Mack wondered if he got it one horrible winter driving an unheated, repossessed car from Regina. Genealogy now suggests Gramma herself may have been a latent carrier; when she was young in Scotland, her mom suffered fourteen months at home from TB before she died. And two of Gramma’s other children got TB.

The hillside setting for the Sanatorium is beautiful, yet it’s a sad place on Pelican Lake in southwestern Manitoba. Too many Manitobans have a painful family story about “the San.” But for me, it’s more complicated. That’s where Dad met my mom, Dorothy Cumming. She was also of Scottish immigrant stock. One of four girls, she studied nursing. Along with teaching and secretarial work, this was one of few jobs for a woman of that time. However, her hopes and plans went off the rails when she got TB in nurse training at age twenty-one and was admitted for four years before going on staff as a nurse. Things happen.

Dad wasn’t expected to ever leave the San. After eight years he did. But he was soon re-admitted for a year and that’s when Dad proposed to Mom. Decades later, I drove Mom there and she pointed to the window where the big event happened. Marriages among patients and staff were common. After a kidney removal and Dad’s second discharge – with hope of a life ahead – they married in 1943 and lived on McMillan Avenue in Winnipeg where Gramma ran a boarding house after my grandfather’s death at Selkirk. Despite doctors’ advice and two more re-admissions to the San for Dad – which must have been so discouraging – they had a family beginning with my oldest sister, Charlotte.

Mr. Chipman offered Dad work at the Fort managing a peat moss harvesting operation. Chipman and Henry Borger had bravely invested in what they called, with considerable poetic geographic licence, the “Arctic Peat Moss Company.” My other sister, Elizabeth, was then born after which Mom and Dad bought a house at 606 Portage Avenue – perhaps unwisely under a blanket of mill smoke. As a surprise, I mean umm, a gift, I popped out on a warm summer day eight years after Elizabeth, thank you. That was July 7, 1955, the day Charlotte lost a piece of her finger in the electric fan. Mom would say, “You were born on the seventh day of the seventh month at seven in the morning!” She’d also say, “I thought it was menopause!” By then Dad’s health worsened again and he’d taken a less stressful job as an agent with Manufacturer’s Life Insurance.

Dad passed away in 1957 at forty-eight when I was two. Mom explained it was like a strained thread giving out. I have little memory of Dad except for how thrilled he and Mom were when I took apart – and put together – a flashlight on their bed. Or when he left for the Winnipeg General Hospital for the last time. And I recall sometime after, I asked Mom, “What happened to that man who lived here?” I suspect I had questions because the matter was never spoken of. I can’t remember how she answered, but it must have been heart-breaking for her.

After he died, the family’s former United Church minister wrote that Dad was the most Christ-like person he’d ever met. One of Dad’s employees at the peat moss company told the local paper Dad was the best boss he ever knew. Dad left a legacy of respect that I heard about from good folks who understood what to say to a boy.

Mom, of strong CCF roots, told me Dad, of strong Liberal roots, was the campaign manager for a local Liberal in the forties. It was actually for a “Liberal-Labour” candidate, Mel Newman. The party label was a concoction of the Labour-Progressive Party, which were really the Communists, the United Auto Workers and the Ontario Liberal Party trying to co-opt union support that would otherwise go to the CCF. Mel and two other “Lib-Lab” MPPs sat of course with the Liberals in the Ontario legislature. If there was one point of division between my parents, it was their political views. Many years later when Mom herself was dying, she astonishingly confided that she wondered if their union would survive this. She confessed that she surprised and surely embarrassed Dad, when at a social gathering of local Liberals, she said, “Well, you know us CCFers!” If their love prevailed over their illness, it would surely prevail over their politics. Perhaps being weary brings too much focus on what makes us different.

I had no father in an era when all the kids I knew in town, except for two or three, had dads. Others felt really bad about it. Mrs. McLennan couldn’t come over at Christmas without crying. I felt agonizingly bad for Mom but not for myself. Family doted on me. Some pals told me I had it made. For example, I’d learned where all the wood was “available” to build my own irregular backyard fort and Donnie down the alley said he wished he didn’t have a dad too, so he could build one just like it in his backyard.

The Fort was the learning ground that offered me life lessons, many helping in public office. When my friend Johnny ran into our yard with a peashooter in his mouth, tripped and fell on his face, staggered to the back door with blood gushing from his mouth saying, “Awgg, gurgle, gurgle,” and Mom said “Oh my gosh!” and for years said, “I was never so beside myself,” I learned something for sure. While I have your attention: Stop running with a peashooter in your mouth.

And when Johnny and I smashed onto the sidewalk every milk bottle that cluttered the Tibbetts’ porch, those witnesses turned us in so we could learn. And I also learned to never open cereal boxes for the great prizes, at least before Mom had a chance to buy a box. I retrieved the whole set of The Sword in the Stone plastic rings. I bet they’d be worth over four bucks today. Why were those valuable things at the bottom under all the crunchy crap? I was a cereal killer. Look up “punitive justice.”

As Mom slaved away in the house on the TB Christmas seal campaign, Chuckie and I, out front with our snowballs hardening into ice balls, tossed one at old lady Nelson as she trudged by, still with her original teeth. I learned from that too – really well because it was not easy saying “Sorry” looking into her face with her tooth missing like that. Look up “restorative justice.”

But honestly, I wasn’t a big troublemaker. A teacher told Mom at the Grade 6 parent night that he’d never heard of me.

And I learned I’m maybe not so smart. After all, I used logs washed up on the shore of Rainy Lake to build a raft. They were “deadheads” – logs that sink. I narrowly avoided a nickname from that.

I learned that Fay Hay, from near Ray, was a funny name. And the names of the Bank of Commerce managers on Scott Street who helped Mom: Hal and Cal. More so the President of the Horticultural Society, Rose Busch. My pal Jim showed me the jewellery store called Garton’s was “snot rag” backwards. Watch what you name things.

In the early grades, I learned it was an absolute joy to run to the front of the class when the teacher left the room, squat on the wastebasket and mouth fart. “Now where were we? Class!”

I learned from the library’s Enid Blyton Secret Seven and Famous Five books the skill of “shadowing” people with Jim. We were wise to their sinister motives, which were not innocent daily activities. We took photos of them which might still be somewhere. This was perfect training to be in a shadow cabinet in politics. A girl I grew up with recently told me there’s a different name for this behaviour now: “stalking” or something.

Elusive men hung out north of the subway around a fire in the bush. We spied on them to save the town from trouble. All they did was sit there with their bottles. One day, we slipped into their camp and filled one with pee. We later found it empty. I wonder what they said. “Hey Scabs, this whiskey tastes like little kids’ pee. Here, don’t cha think?” I learned the joy of mischief.

At nine-thirty each night, the paper mill’s whistle told kids the boogie man was out and it was time to get home. The curfew was never enforced, so our first lesson about the law as youngsters was how it’s all bark and no bite. The boogie man was real though; we knew that. I saw the child-thirsty menace myself many times, with his ominous long brown coat. He lived on Third Street I think. I heard there was also a witch in the McIrvine area of town and I later figured out it was my own child-loving Gramma. Kids are so mean. I learned to watch who you label.

Jim brought over a good hammer to work on the fort. We needed nails and found some in our back fence. I was pulling a stubborn one. Jim directed me, right behind. With a good yank and a bit of a slip-up, the claw went straight to his skull. It was so bad, there was no blood until after Mom answered the back door. Whether it was a mere flesh wound remains in contention. Two years later, I gave him a heavy Christmas present, a large wrapped box. When he opened it Christmas morning he found a bag of kitty litter, because I thought he still had a cat, and his hammer. Jim said he’d sue because the assault ended his certain destiny to get the Nobel Peace Prize. I’m sure I have a counterclaim; he negligently stood eighteen inches behind a nine-year-old with a live hammer. And he benefitted from me knocking some sense into his head...

Table of contents

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Part V

- Part VI

- INDEX