![]()

1

Melancholy and the Fall

In a letter to Emily Coleman dated October 30, 1938, Barnes returns again to the problem of evil, writing this time of Wordsworth’s failure to confront its presence in the created world:

Fleeting thoughts: Peter Bell (just re read it) we are not satisfied with it because it is not evil enough. For what are we thirsty!?! Marvellous the ass standing with hanging head over the water. Read the ode [“Intimations of Immortality”] […] it is beautiful, almost as if he had made the trees, lakes and moon himself, nature repeated, and thats [sic] just why I cant [sic] love it as you love it, its [sic] too new and pure with the devil left out, he feels himself cross, discontent, but he does not braid the two together. He does for a minute in Peter Bell. Nothing lovelier than “the moon doth with delight, Waters on a starry night Are beautiful and fair.”

The reference here is to the following lines from Wordsworth’s “Immortality Ode” on the glory of Creation: “There was a time,” Wordsworth writes, “when meadow, grove, and stream,/ The earth, and every common sight,/ To me did seem/ Apparelled in celestial light,/ The glory and the freshness of a dream” (l.1–5). Yet as Wordsworth also records, the experience of such beauty can lapse into an inaccessible past, draining “celestial” presence into its inoperative residue: “The things which I have seen I now can see no more. […] But yet I know, where’er I go,/ That there hath passed away a glory from the earth” (l.9, 17–18). Such alienation from the enchanted heart of nature constitutes an “evil day” (l.42).

Despite the moral and aesthetic pathos registered in these lines, however, Barnes considers the ode inadequate in its confrontation with “evil.” Like Peter Bell (1819), which remains “not evil enough,” the “Immortality Ode” has “the devil left out.” What she gleans from Wordsworth appears to be primarily the promise of redemption from this “evil day.” In fact, insofar as nature’s “Inmate Man” is never fully divorced “From God, who is our home,” humanity’s entry into Creation presents not so much a thoroughgoing Fall into evil, but a mitigated “sleep and a forgetting”:

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting,

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

(l.58–66)

Wordsworth suggests in these lines that we are only partially alienated (“not in entire forgetfulness”) from our divine provenance “elsewhere,” in “God […] our home,” leaving us still wrapped about with “trailing clouds of glory” in this world, infants swaddled with heaven’s residue. If something of a Fall is intimated here it is not one that produces a total, irremediable division between “Heaven” and the status corruptionis of existence in the natural world. Evil does not quite prevail.

Barnes’s reading of this major poet of English Romanticism latches onto his denial of the “devil.” For her, Wordsworth’s poem merely “repeat[s]” the natural world in and as the written word, returning Creation to the glory of its first days. The belated creator thus presents a restorative iteration of his predecessor: “almost as if he had made the trees, lakes and moon himself, nature repeated.” Barnes sums up her resistance to Wordsworth’s Romanticism: “Wordsworth, these nature writers, seem to me to clean nature up too much.” The traces of the Fall in their poems are ultimately submerged or transformed via an idealizing aesthetic that appears to redeem Creation by means of a backward repetition. Unconvinced of the restored glories of “moon,” “lakes,” and “trees,” Barnes anticipates their undoing: “But I sit with Judas and wonder when these will be betrayed.”

In the same 1938 letter to Coleman, Barnes hence acknowledges her preference for another English Romantic, William Blake, known for marrying “the two verities, Heaven and Hell”—as she puts it elsewhere (Barnes 1939a)—as well as Emily Brontë for the “reality of Heathcliff and Cathy” in Wuthering Heights (1847). Their respective visions of evil will in fact later earn them a place, together with Baudelaire, de Sade, and others, in Georges Bataille’s 1957 collection of essays, Literature and Evil. The notes gathered in Barnes’s letters thus suggest a certain preoccupation with the nature of evil, and its relation to beauty, goodness, and the created world. Having discussed her dissatisfaction with Wordsworth, she considers the entanglement of good and evil with an idiosyncratic formula—the “holy imprint of the Devil hoof”:

Perhaps only direction of good and evil; you fall (the fall of Lucifer) and you are a fallen angel; you rise (the heavenly chariot,—race with Einstein) and you are: Christ—things that come down, meteors, angels, storms, we seem to think evil, things that rise, nature, trees, flowers, fire, prayers, good; no, on the other hand this wont [sic] do—there are showers of good omen, and there are uprisings of evil, its [sic] not direction then but kinds in direction—

This brief schematization of good and evil into rising and falling vectors only gets her so far. She concedes: “this is all insane, but I’m just putting down for fun what runs through what is called my head.” In a post-Nietzschean age purportedly beyond good and evil, Barnes’s continual return to evil’s mystery provokes her into the role of a theological bricoleuse, crafting and re-crafting answers in response to an unending melancholy.

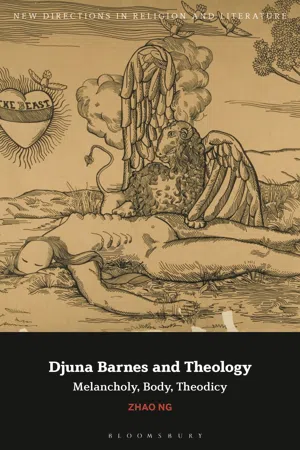

As I have suggested, the experiences of suffering and evil in life that contribute to Barnes’s understanding of melancholy unfold a specific manner of being in the world, a specific existential mood into which we are thrown. Barnes’s various thoughts on the nature of melancholy are often pinned to a notion of the Fall, suggesting a feature of ontological volatility in life that leaves the afflicted subject adrift with its symptoms, propelling it in various “kinds” of “direction,” and even—as we will see—expelling it from its own body. This unifying theme of the Fall suggests the relevance of an ontological understanding of melancholy capable of disclosing a consistent, structural configuration beneath its variegated field of presentation. Just as Ferber’s consideration of the “ontological structure” of mood and melancholy enables a “vertical rather than horizontal direction of investigation,” gathering together the “history” of melancholic manifestations into various determinations of “the relationship between a subject and the world,” so too might such an approach constellate the manifold Barnesian variations on the theme into a recognizable pattern (Ferber 2013, 10). The myth of the Fall, understood ontologically as the rupture from unity or harmony, finds a plethora of ontic equivalents across Barnes’s writings. Otherwise put, where we are said to fall from and into is subject to numerous re-articulations. Ferber’s reconstruction of the “melancholic mood” from Heidegger, Benjamin, and Freud, thus points to its “non-intentional” structure: melancholy, in a strict sense, has no object that can be brought into full phenomenological presentation (2003, 8, 42–50).1 As a loss to the second degree—a lost loss or a “cognitively inaccessible loss” (Bahun 2013, 5)—its formulation is always based on a reconstruction. The ontological wound that the Fall names, casting the subject from union (with Nature, the Mother, God, etc.) into its divided existence may be variously thematized. The postlapsarian condition in Barnes thus presents a state of division from a prior wholeness: it is, by turns, post-Romantic (after Wordsworth); post-medieval, as derived from Edwin Muir’s reading of Hermann Broch;2 post-Reformation, following the “crisis of the Christian soteriological narrative” that the Lutheran interrogation of the authority of the Church and the sacraments entailed (Weber 2015, 95–9);3 post-war, as recorded in her memoirs of the “war of nerves” in France, when German invasion was imminent;4 post-pastoral, as depicted in her anti-pastoral with its animals left out-of-joint with time and nature;5 post-Sapphic, as in the disruption in Ryder of a sororal Eden by Wendell’s appearance on the horizon, with “thundering male parts hung like a terrible anvil” (see the result of this in Figure 1.1—Ryder, 40–2); as well as, of course, post-nature, reiterated in the early short stories through to her late works, encapsulated none too subtly in the title of a Vanity Fair contribution (Barnes, “Against Nature”).

Melancholy’s association with an ontological wound that divides the subject from a preexisting harmony is thus, on one level, structural. The terms in which such a division is articulated, however, are plural and historically implicated. Charles Taylor’s observation that modernism’s aesthetic and philosophical projects reveal a symptomatic pursuit of “unmediated unity” or “merging with the other” is given diverse instantiation by Bahun: as “a pursuit of ‘oceanic feeling’ (Freud), longing for the ‘primal unity’ of the infant-mother dyad (Klein), the homeless’s search for ‘undivided totality’ (Lukács), and approximation of Being (Heidegger)” (Taylor 1989, 471; Bahun 2013, 21). Melancholy, in this sense, names the place of the subject’s alienation from its origin and envisaged destination in “unmediated unity,” between a suffering world and the redeemed world it tends toward. In situating melancholy in the liminal region between a “mood” into which one is already thrown and a “counter-mood” that the artwork produces, the emphasis is placed on the ek-centric predicament of the subject, withdrawn from itself, its own body, and its regular negotiations with the world, without a corresponding relocation within any immediately available soteriology. Understood ontologically in terms of the Fall, melancholy—as we now move on to observe—also entails a phenomenology of embodiment that alienates one from the immediate flesh. Its corporeal markers, registered across the Barnesian oeuvre, range from the everyday (laughing and crying), to the more extraordinary (sex- and species-hybridity).

Figure 1.1 Djuna Barnes, “All Because of Wendell!” Ryder. © The Authors League Fund and St. Bride’s Church, as joint literary executors of the Estate of Djuna Barnes.

Laughing and Crying

In the memoirs of her time spent in Paris as an American expatriate among the literary and artistic avant-garde of the 1920s, Barnes considers the appeal of the French polymath Jean Cocteau: “he set the tragic muse on the circus horse! Fratellini and Hamlet mixed; Greek legend, Christian morality, and the street fair were brought together” (Collected Poems, 236). Though attributed to Cocteau, neither the heady encounter of heaven and Hellenism at the carnival nor the mixing of stage clowns and tragic metaphysician is foreign to Barnes. The “circus horse,” like the “bucking mare,” saddles the artist with the contrary forces of the comic and tragic, rattling her back and forth from pole to pole. Among the drafts of the poetry of her later years, unpublished in her lifetime, a series collected under the header “Laughing Lamentations” suggests that her own remark regarding the “hilarious sorrow” of Dan Mahoney, the living prototype for Nightwood’s Matthew O’Connor, informs her thoughts on the nature of laughing and crying (Barnes 1958b). The openings of two of these drafts are a sardonic portrayal of the body transported by these buffeting affects:

When first I practised all my eyes in tears,

With flapping nostrils like a blowing horse,

Laughter under-water bow’d her head

Like any peasant in a praying stall.

(Collected Poems, 221, 224)

Pushing physiology to the fore, Barnes’s depictions exhibit the hidden conjunction of laughing and crying in that common moment when the body transgresses its own boundaries through its orifices, tearing, snorting, blowing, sniffling, and siffling (“O siffleur, too sinful and too jubilant”—Collected Poems, 221). Intimations of sin and repentance, joy and guilt, throw passing light and shade over these images, unsettling them from the contours of any fixed affect.

This presentation of the body in ek-stasis, out-of-joint with itself and with God, owes something to the writings of the French symbolists, including the Comte de Lautréamont, rediscovered and revered by the Surrealists in the interwar years, for whom Barnes professed admiration till the end of her life (O’Neal 1990, 48), as well as Baudelaire, in particular, his tract on laughter, De l’essence de rire (1855). The “physiologists of laughter,” Baudelaire claims, are in “unanimous agreement” that “the comic is one of the clearest marks of Satan in man.” It is, in fact, a “symptom”:

human laughter is intimately connected with the accident of the ancient fall, of a physical and moral degradation. Laughter and grief express themselves through the organs that have the control and the knowledge of good and evil, the eyes and the mouth […] the laughter of his lips is a sign of as great a state of corruption as the tears in his eyes.6

(Baudelaire 1981, 143–6, 150)

Laughter and tears, as symptomatic manifestations of humanity’s loss of “unity,” evidence the disequilibrium of the body’s relation to itself, defiling the very image of God: “God, who desired to multiply his own image, did not place lion’s teeth in man’s mouth—but man bites with his laughter; nor did He place, in man’...