![]()

I

Bridging the Sea

World literature owes its earliest awareness of the sea and the dangers of seafaring to Homer and his protagonist Odysseus:

When we had left that island and no other land appeared, but only sky and sea, then verily the son of Cronos set a black cloud above the hollow ship, and the sea grew dark beneath it. She ran on for no long time, for straightway came the shrieking West Wind, blowing with a furious tempest, and the blast of the wind snapped both the fore-stays of the mast, so that the mast fell backward and all its tackling was strewn in the bilge. On the stern of the ship the mast struck the head of the pilot and crushed all the bones of his skull together, and like a diver he fell from the deck and his proud spirit left his bones.1

This sea, the Mediterranean, had been discovered several millennia before (ninth to eighth century BCE), when hunters, gatherers and farmers from Asia Minor settled the islands of Cyprus and Crete. From there the farmers also reached the Greek mainland, most notably Thessaly. Evidence of intensive maritime trade remains limited, however, with the exception of obsidian tools from the island of Melos and the shells that became popular as adornment.2

The beginnings: Phoenicians and Greeks

Scholars have noted an intensification of exchange in the second millennium BCE, when people travelled voluntarily or as captives and goods were transported between the coasts and islands of the (eastern) Mediterranean. Political centres such as Avaris, ‘Venice on the Nile’, Ugarit in present-day Syria and Knossos on Crete stimulated long-distance trade. The Bronze Age ship from Uluburun discovered in 1982 thus carried not just copper and tin but also glass from Egypt and many precious amber objects from the Baltic, whose magical properties were prized in the Mediterranean region.3

Inhabitants of the Cyclades played an important role as intermediaries, who made contact with other islands and the coastal mainland in their canoes. One innovation was the introduction of a sailing ship – familiar to us from seals – with a lower keel, which could travel more quickly over long distances and transport more cargo. In the Odyssey Homer describes such a craft setting sail:

And Telemachus called to his men, and bade them lay hold of the tackling, and they hearkened to his call. The mast of fir they raised and set in the hollow socket, and made it fast with fore-stays, and hauled up the white sail with twisted thongs of ox- hide. So the wind filled the belly of the sail, and the dark wave sang loudly about the stem of the ship as she went, and she sped over the wave accomplishing her way.4

FIGURE 1 Ship procession: Fresco from the Bronze Age in the Minoan town Akrotiri, Santorini, Greece. © Wikipedia Commons.

For a long time, the new ships stimulated shipping and trade as well as the establishment of ports. In the second millennium BCE, the centre of these activities was initially Minoan Crete, which was named after its storied king and occupied a favourable position between the Aegean, Anatolia and Egypt. Palace settlements such as Knossos, Malia and Phaistos were erected along its coasts. Archaeological evidence shows that overseas goods brought to Knossos included copper from present-day South Russia, lapis lazuli from Central Asia, silver from Attica and gold and ivory from Egypt. The goods were transported to Anatolia or Egypt along the traditional routes and then shipped to Crete. In exchange, Crete offered woollen fabrics, wine and olive oil as well as essential oils and medicinal herbs and wood, for which there was demand in Egypt.

The palace city of Mycenae on the Peloponnese was located at the intersection of the western and eastern Mediterranean. From here there was easy access to the Gulf of Argos and Crete; similarly, one could reach the Adriatic via the Gulf of Corinth and the Aegean via the Saronic Gulf. We accordingly find Mycenaean ceramics in both the West and the East. Apart from painted ceramics, the Mycenaeans exported weapons and in exchange imported copper and tin, the components of the bronze used to make weapons. The copper came from Attica, and tin was transported from the Iberian Peninsula by a Mycenaean fleet.5

Mycenae is also associated with the heroes of the Iliad and the Odyssey, who could rightly claim to have travelled the entire known world of their day. After returning from the victorious siege of Troy, Menelaus could boast

For of a truth after many woes and wide wanderings I brought my wealth home in my ships and came in the eighth year. Over Cyprus and Phoenicia I wandered, and Egypt, and I came to the Ethiopians and the Sidonians and the Erembians, and to Libya.6

Historically, however, the Greeks were preceded as maritime people by the Phoenicians (Gr. Phoinikes), whom Homer disdained for their business sense. Their name came from the purple dye obtained from the Murex mollusc found along the coast of the Eastern Mediterranean, one of the commodities in which they traded. Phoenicia, which corresponded roughly to present-day Lebanon, had a number of commercial centres, for example, Ugarit in the north (destroyed c. 1190 BCE), Byblos and Sidon. Apart from Tyrian purple, the main export was native cedar, which the Egyptians in particular used for shipbuilding. A papyrus in a Moscow collection, for example, recounts the journey of the priest Wenamun, who around 1075 BCE was sent from the temple of Amon in Thebes (Upper Egypt) to acquire cedarwood for the ship of the god Amon.

This account and other Egyptian sources provide insight into trade in Byblos as well as the goods used to pay for cedarwood: gold and silver vessels, linen clothing, papyrus rolls, cowhides, ropes, lentils and fish. Cyprus was colonized from Tyre, another Phoenician centre, which was of interest particularly for its deposits of copper. Other Phoenician trading posts followed in Sicily, Sardinia and North Africa, where Carthage would develop as a new centre.7

Around 800 BCE, the Phoenicians advanced into the Atlantic through the Straits of Gibraltar and founded an outpost in Gadir (Cádiz) on an island on the Atlantic coast. From there, Phoenician settlements spread eastwards along the coast. The Phoenicians lived from agriculture and fishing as well as trade. At times they competed with the Etruscans, who shipped wine from their main settlements in central Italy to present-day southern France.

South of the Straits of Gibraltar, the Phoenicians settled the West African coast, where the trade in ivory, ostrich eggs, exotic animals and slaves beckoned. These emporia were later integrated into the Carthaginian network.8

The Phoenician presence is evident from sacred sites and cultural commonalities. The Phoenicians venerated Melkart, the principal deity of Tyre, who protected shipping and foreign outposts, and erected shrines to the god in the Mediterranean world and Gadir as well as on Cyprus. The graves of native Iberians also contain Phoenician figurines, which suggests the spread of similar practices or beliefs among local elites.9 Decorative metal drinking vessels manufactured in various ‘Phoenician’ workshops in Crete, Anatolia or Iberia also indicate Phoenician influence on ways of life more generally.10

The Phoenicians also mediated contacts between the ‘early Greeks’ and the Mediterranean world, as is evident from funerary objects. The alphabet, without which Homer’s textualization of the old stories and songs would have been impossible, was also developed by the Phoenicians and adapted by the Greeks.11

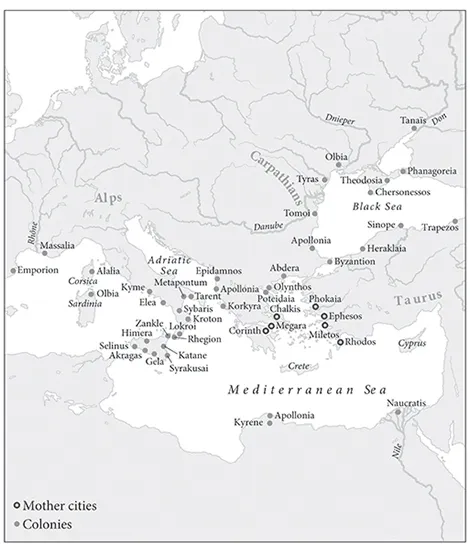

Around the middle of the eighth century BCE, the Greeks began to advance almost simultaneously into the western Mediterranean world. Many cities such as Ampurias (Emporion), Marseille (Massalia), Nice (Nikaia), Antibes (Antipolis), Naples (Neapolis), Reggio (Rhegion), Syracuse (Syrakusai), Taormina (Tauromenion) and Palermo (Panormos) owe their Greek names to this process of colonization.

Sicily and southern Italy in particular were settled far more densely than elsewhere and thus known as Magna Graecia. The settlers brought their political institutions as well as their deities and cults. One of the first settlements, which has been well studied by archaeologists, is Pithekussai on Ischia, whose iron ore deposits made it attractive. In 700 BCE the town had 4,000 inhabitants who originally came from Etruria, Sardinia, Phoenicia, North Africa and the Greek motherland.12

The search for metals finally took the Greeks to the southern coast of the Black Sea. Soon they presumably also arrived at the great rivers of the Eurasian steppes. The Black Sea region was rich in fish and wood for shipbuilding, and also offered a low population density.

The journey to the Black Sea crossed a psychological boundary beyond which the Amazons and Hades were not far distant. Crimea was home to the Tauri, who had sacrificed Iphigenia to Artemis, and to the east, in the Caucasus, Prometheus had been chained to a rock until he was freed by Herakles. It was, however, above all the city-states of the Ionian coast, which, like Miletos, profited from trade (cereals, metals, fish) with the region around the Black Sea and controlled the passage through the Dardanelles and Bosporus. The colonies of Sinope on the south coast, Dioskurias near present-day Sukhumi at the foot of the Caucasus, Pantikapaion (present-day Kerch) at the entrance to the Sea of Azov and Olbia at the mouth of the Bug River opened up trade with the hinterland. According to Plato, putting his words in Socrates’ mouth, in the fifth century BCE Greek settlements spread out like ‘ants or frogs about a pond’, with sailing ships travelling along the coasts and canoes along the rivers. The Black Sea colonies occupied an important place in the Greek economy. If the winds were favourable, one could sail from the Sea of Azov to the island of Rhodes in nine days and supply the Ionian cities and the Greek mainland with vital cereals – if Sparta was not blocking the Dardanelles. Fish was also available in large quantities and was preserved with local salt.13 In first century BCE Rome, salt fish from the Black Sea was considered a delicacy. Exotic animals like pheasants, which were brought from there to Greece and Italy where they were bred, were also highly prized.14

MAP 1 Greek emigration

Thalassocracies: Athens, Alexandria, Carthage and Rome

The Greek word thalassokratia refers to a maritime power; however, this was not a simple sea power, but the establishment of a realm that linked territories scattered across the waters with the aid of ships, thereby creating a particular political space. Thuc...