![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

... the indians

are not composed of

the romantic stories

about them ...

—John Newlove, The Pride

SOME YEARS AGO a friend and I decided to pay a visit to Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. Located where the prairie meets the foothills in southwestern Alberta, Head-Smashed-In is a high cliff over which Native people stampeded the great herds of buffalo hundreds of years ago. Archaeologists believe that people used this place as a slaughterhouse for almost 6,000 years. The United Nations has declared it a World Heritage Site, one of the most culturally significant places in the world.

We drove south from Calgary on a sunny Thanksgiving day. On our left the flat plain ran away to the horizon under a wide, blue sky; on our right the land folded into rolling hills all the way to the Rocky Mountains, faintly visible in the distance. There were few signposts along the way and we had begun to fear that we had missed the turnoff when at last we spotted the sign and left the highway on a meandering strip of asphalt heading west toward the mountains. Just about the time we once again thought we must be lost, we arrived at a gravel parking lot, seemingly in the middle of nowhere. We were there.

The site at first seemed unimpressive. The visitors’ centre, actually a mini-museum, is a concrete building several stories high embedded in the face of the cliff. It appears to have been built to make as little impact on the landscape as possible. Entering at the front door, we climbed up through a series of levels and emerged at the top of the cliff, at the edge of the buffalo jump, right where the stampeding animals would have run out into empty space and begun the long, bellowing fall onto the rocks below.

The anthropologist George MacDonald has written that the three holiest places in Canada are a row of stone statues at Eskimo Point in Nunavut, Bill Reid’s large cedar carving, “The Raven and the First Men,” at Vancouver’s Museum of Anthropology, and the abandoned Haida village of Ninstints on Anthony Island. Well, I thought, as I looked out from the clifftop across a vast sweep of undulating prairie, lightening and darkening as the billowing clouds obscured the sun and set it free again, add a fourth; if by holy you mean a place where the warm wind seems to be the earth breathing, a place where personal identity dissolves temporarily, where you can feel the connectedness of lives back through time to be a reality, and not just an opinion.

Back inside the museum, looking at the various items depicting the history of the buffalo and the people who hunted them, my attention shifted from the display cases to the people who were tending them. I became aware that the facility was staffed entirely by Indians (Peigan, as it turned out, from a nearby reserve). But I found myself thinking that they didn’t look like Indians to me, the Indians I knew from my school books and from the movies, the Indians, in fact, who were depicted inside the museum displays I was looking at. That is where most of us are used to seeing Indians, from the other side of a sheet of glass. But at Head-Smashed-In, they were running the place. They stood around in jeans and dresses and plaid shirts—not feather headdresses and leather moccasins—talking and laughing. If curious visitors like myself asked them something, they answered thoroughly but not pedantically: as if this was some-thing they knew, not something they had studied.

After a long afternoon learning about the buffalo, I left Head-Smashed-In dimly aware that I had changed my mind about something. It had been an encounter not just with an important place in the history of the continent, but also with an idea, my own idea about what an Indian was. If I thought I had known before, I didn’t think I knew anymore. And perhaps that is where this book began. How had I come to believe in an Imaginary Indian?

II

In 1899, the poet Charles Mair travelled into the far Northwest as secretary to the Half-Breed Scrip Commission, appointed by the government in Ottawa to carry out negotiations related to Treaty Number Eight with the Native people of northern Alberta. Negotiations began on the shore of Lesser Slave Lake, before a large tent with a spacious marquee beneath which the members of the official party arranged themselves. The Native people, Beaver and Metis, sat on the ground in the sun, or stood in small knots. As the speeches droned on through the long June afternoon, Mair observed the people as they listened to what the government emissaries had to say. “Instead of paint and feathers, the scalp-lock, the breech-clout, and the buffalo robe,” he later wrote:

there presented itself a body of respectable-looking men, as well dressed and evidently quite as independent in their feelings as any like number of average pioneers in the East ... One was prepared, in this wild region of forest, to behold some savage types of men; indeed, I craved to renew the vanished scenes of old. But, alas! one beheld, instead, men with well-washed unpainted faces, and combed and common hair; men in suits of ordinary store-clothes, and some even with “boiled” if not laundered shirts. One felt disappointed, even defrauded. It was not what was expected, what we believed we had a right to expect, after so much waggoning and tracking and drenching and river turmoil and trouble. [1]

Unlike most Canadians of his time, Charles Mair possessed extensive knowledge of the country’s Native people, living as he had for so many years as a merchant trader in the future province of Saskatchewan. He knew well that the contemporary Indian no longer galloped across the plains in breechcloth and feathered headdress. However, Mair did expect to discover in the more isolated regions of the north a Native population closer to his image of the picturesque Red Man. His disappointment was profound when instead he found “a group of commonplace men smoking briar-roots.”

III

Two very similar experiences, almost a century apart. Charles Mair, myself, and how many other White people, having to relearn the same lesson: Indians, as we think we know them, do not exist. In fact, there may well be no such thing as an Indian.

Indirectly, we all know this to be true; it is one of the lessons we learn as school children. When Christopher Columbus arrived in America five hundred years ago he thought he had reached the East Indies so he called the people he met Indians. But really they were Arawaks, and they had as much in common with the Iroquois of the northern woodlands as the Iroquois had in common with the Blackfoot of the western Plains or the Haida of the Pacific Coast. In other words, when Columbus arrived in America there were a large number of different and distinct indigenous cultures, but there were no Indians.

The Indian is the invention of the European.

Robert Berkhofer Jr. introduced me to this unsettling idea in his book, The White Man’s Indian. “Since the original inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere neither called themselves by a single term nor understood themselves as a collectivity” Berkhofer began, “the idea and the image of the Indian must be a White conception. Native Americans were and are real, but the Indian was a White invention... “ [2]

The Indian began as a White man’s mistake, and became a White man’s fantasy. Through the prism of White hopes, fears and prejudices, indigenous Americans would be seen to have lost contact with reality and to have become “Indians”; that is, anything non-Natives wanted them to be.

IV

This book attempts to describe the image of the Indian, the Imaginary Indian, in Canada since the middle of the nineteenth century. During this time, what did Canadians think an Indian was? What did children learn about them in school? What was government policy toward them? What Indian did painters paint and writers write about? I want to make it perfectly clear that while Indians are the subject of this book, Native people are not. This is a book about the images of Native people that White Canadians manufactured, believed in, feared, despised, ad-mired, taught their children. It is a book about White—and not Native—cultural history.

Many of the images of Indians held by Whites were derogatory, and many were not. Many contained accurate representations of Native people; many did not. The “truth” of the image is not really what concerns me. I am not setting out to expose fraudulent images by comparing them to a “real Indian.” It is, after all, the argument of this book that there is no such thing as a real Indian. When non-Native accounts of Indians are at variance with the known facts I will say so, but my main intention is not to argue with the stereotypes, but to think about them. The last thing I want to do is to replace an outdated Imaginary Indian with my very own, equally misguided, version. My concern is rather to understand where the Imaginary Indian came from, how Indian imagery has affected public policy in Canada and how it has shaped, and continues to shape, the myths non-Natives tell themselves about being Canadians.

Every generation claims a clearer grasp of reality than its predecessors. Our forebears held ludicrous ideas about certain things, we say confidently, but we do not. For instance, we claim to see Indians today much more clearly for what they are. I hope that my book will undermine such confidence. Much public discourse about Native people still deals in stereotypes. Our views of what constitutes an Indian today are as much bound up with myth, prejudice and ideology as earlier versions were. If the Indian really is imaginary, it could hardly be otherwise.

Take, for example, the controversial 1991 decision by Chief Justice Allan McEachern of the Supreme Court of British Columbia relating to the Gitksan-Wet’suwet’en land claims case. Much of what Judge McEachern wrote about Native culture in that decision could as easily have been written by another judge one hundred, two hundred, three hundred years ago. In dismissing the Natives’ claim, he wrote: “The plaintiffs’ ancestors had no written language, no horses or wheeled vehicles, slavery and starvation was not uncommon, wars with neighbouring peoples were common, and there is no doubt, to quote Hobbs [sic], that aboriginal life in the territory was, at best, ’nasty, brutish and short.’” [3]

It is unclear whether Judge McEachern was aware when he borrowed this well-worn phrase that Thomas Hobbes actually coined it in 1651 to describe “the savage people of America” as he believed them to be. And many Europeans agreed with him. Because Native North Americans were so different, had so few of the “badges of civilization” as Judge McEachern calls them, it was seriously debated whether they could properly be called human beings at all. I would have thought, however, that in the three hundred and forty years separating Thomas Hobbes and Judge McEachern, our understanding of aboriginal culture might be seen to have improved. But obviously not.

Of course, non-Natives have held much more favourable opinions about Indians over the years. The Noble Savage, for instance, is a venerable image, first used by the English dramatist John Dryden in his 1670 play, The Conquest of Granada, to refer to the innate goodness of man in a perceived “state of nature”:

I am as free as nature first made man,

Ere the base laws of servitude began,

When wild in the woods the noble savage ran.

For an example closer to home, we need look no further than the aforementioned Charles Mair, who wrote in his long poem, Tecumseh:

... There lived a soul more wild than barbarous;

A tameless soul-the sunburnt savage free-

Free, and untainted by the greed of gain:

Great Nature’s man content with Nature’s good.

Savage, when used by Dryden and Mair, meant innocent, virtuous, and peace-loving, free of the guile and vanity that came from living in contemporary society. I don’t think I have to argue the fact that many non-Natives continue to believe that Indians have an innate nobility of character which somehow derives from their long connection with the American continent and their innocence of industrial society.

Ignoble or noble? From the first encounter, Europeans viewed aboriginal Americans through a screen of their own prejudices and preconceptions. Given the wide gulf separating the cultures, Europeans have tended to imagine the Indian rather than to know Native people, thereby to project onto Native people all the fears and hopes they have for the New World. If America was a Garden of Eden, then Indians must be seen as blessed innocents. If America was an alien place, then Indians must be seen to be frightful and bloodthirsty. Europeans also projected onto Native peoples all the misgivings they had about the shortcomings of their own civilization: the Imaginary Indian became a stick with which they beat their own society. The Indian became the standard of virtue and manliness against which Europeans measured themselves, and often found themselves wanting. In other words, non-Natives in North America have long defined themselves in relation to the Other in the form of the Indian.

As time passed, colonist and Native had more to do with one another. But Euro-Canadians continued to perceive Indians in terms of their own changing values, and so the image of the Indian changed over time. Close contact revealed differences between the idealized vision of the noble savage and the reality of Native culture. As White settlement spread, conflict increased. As long as Natives remained valuable allies in the wars the colonial powers waged against each other, the image of the Indian remained reasonably positive. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, these wars were over and whites no longer needed Native military allies. Natives had become marginal to the new issues which preoccupied Canadian colonists: how to wrest a living from the country, how to create durable political institutions, how to transform a set of isolated colonies into a unified nation.

At this point Whites set themselves the task of inventing a new identity for themselves as Canadians. The image of the Other, the Indian, was integral to this process of self-identification. The Other came to stand for everything the Euro-Canadian was not. The content of the Other is the subject of this book.

V

A word about terminology. There is much debate these days about the correct term for indigenous Americans. Some do not object to being called Indians; others do. Alternative terms include aboriginals, Natives, Amerindians, First Nations peoples and probably others I have not heard. In this book I use the word Indian when I am referring to the image of Native people held by non-Natives, and I use the terms Natives, Native people or aboriginals when I am referring to the actual people. What to call non-Natives is equally puzzling. White is the convenient opposite of Indian but it has obvious limitations. So, in this age of multiculturalism, does Euro-Canadian, an awkward term anyway. I hope readers will forgive me for using all three. It is part of the legacy of the Imaginary Indian that we lack a vocabulary with which to speak about these issues clearly.

![]()

PART ONE

Taking the Image

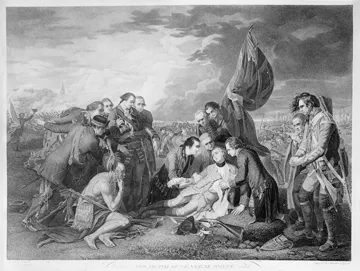

ONE OF THE MOST FAMOUS historical paintings ever done on a Canadian theme is “The Death of General Wolfe” by Benjamin West. The huge canvas depicts the English general, James Wolfe, expiring on the Plains of Abraham outside the walls of Quebec City. In the background, his triumphant army is capturing Canada for British arms. Wolfe lies prostrate in the arms of his grieving fellow officers. A messenger brings news of the victory, and with his last breath the general gives thanks. The eye is drawn to the left foreground where an Iroquois warrior squats, his chin resting contemplatively in his hand, watching as death claims his commander. The light shimmers on the Indian’s bare torso, which looks as if it might be sculpted from marble.

From its unveiling in London in the spring of 1771, “The Death of Wolfe” was a sensation. It earned for its creator an official appointment as history painter to the King, and became one of the most enduring images of the British Empire, reproduced on tea trays, wall hangings and drinking mugs. West himself completed six versions of the painting. Today it still appears in history textbooks as an accurate representation of the past. Yet as an historical document, it is largely a work of fiction. In reality, Wolfe died apart from the field of battle and only one of the men seen in the painting was actually present. Other officers who were present at the death refused to be included in the painting because they disliked General Wolfe so much.

And the Indian? According to his biographers, Wolfe despised the Native people, all of whom fought on the side of the French, anyway. Certainly, none would have been present at his death. But that did not matter to Benjamin West. Unlike Wolfe, West admired the Noble Savage of the American forest. And so he included the image of a Mohawk warrior, posed as a muscular sage—a symbol of the natural virtue of the New World, a virtue for which Wolfe might be seen to have sacrificed his life.

This famous painting, The Death of Wolfe, by Benjamin West, exemplifies the Imaginary Indian. It is largely a work of fiction, not an actual recreation of the event depicted. Only one of the men attending the dying general was actually pre...