- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Arabian Nights by Michael Moon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE: PASOLINI SCHEHERAZADE

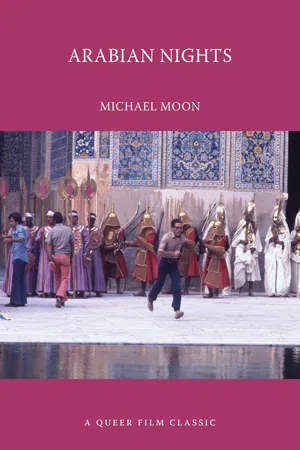

There is an image of Pier Paolo Pasolini directing Arabian Nights that I haven’t been able to get out of my mind as I’ve been writing this book. A production still taken by Roberto Villa, it shows the director dashing off the set during the filming of one of the exterior scenes at the magnificent mosque of Isfahan in central Iran. Several lines of richly costumed performers—turbaned and silk-robed courtiers, scimitar-wielding guards, soldiers in exotic looking helmets and armor—stand ready for filming. To the left of center, three young men in modern dress (an assistant director? a costumer? a props man?) are applying last-minute touches. To the right of center, Pasolini can be seen running out of the frame, his arms pumping vigorously.

Pasolini is immediately recognizable as himself, first of all by the heavy-framed dark eyeglasses he sports—a visual signature of his. Looking at the photo, I’m struck once again by the physical slightness of this fifty-year-old: his head is that of a mature man, but the rest of his body looks like it could be a boy’s. There are about twenty other men visible or partly visible in the shot, and the only other one who appears to be in motion (the crew member approaching the group of guards) seems to be moving at a slow and deliberate pace. The image of Pasolini, in contrast, is captured in such energetic motion that it’s just beginning to blur. He looks to me like some of my favorite images of Tintin, the boy comics hero, dashing into or out of a frame and into the camera, I suspect, to take in the visual composition he is about to film and perhaps to order further last-minute tweaks. The high spirits he shows here would be captured again in a video shot a year or so later in which Pasolini makes some fine adjustments to a group of actors, then dashes back to check the camera’s view. In this case, the scene is one of the most harrowing he ever filmed, a torture and execution near the end of Salò, the controversial and disturbing film he made after Arabian Nights. I can’t remember if we actually see him smiling on video as he dashes around the set, but I remember feeling, as I watched, that his whole body seemed to smile, exuding a palpable joy in his work.

FIGURE 1 Pasolini dashing off the set during filming of Arabian Nights. Photo: Roberto Villa. Photo by permission of Roberto Villa.

The young cineaste Gideon Bachmann visited the set of Arabian Nights and reported that Pasolini appeared to wish that he could do all the jobs of the crew himself (1973–74, 26). This extended even to acting in The Decameron (1971), the first of what he called his Trilogy of Life films, based on various medieval chain-narratives (The Canterbury Tales [1972] is the second and Arabian Nights the third). In The Decameron, Pasolini cast himself in the role of a follower of the great early Renaissance painter Giotto, who as master-artist, presides over a team of assistants.

The great fresco narrative sequences that Giotto developed with the help and in the company of the young men in his studio provide an interesting analogy for Pasolini’s view of his own filmmaking career late in its unfolding, especially the serial-narrative films of the Trilogy of Life. These films often featured the kind of underclass young men to whom he was attracted and whom, in some cases, he loved and befriended; several had appeared in earlier films of Pasolini’s.

Why did Pasolini throw himself into every phase of production when he might have sat back and let his crew do most of the work? In the role of a follower of Giotto in The Decameron, Pasolini raises the question himself near the end of the film, when, after experiencing an ecstatic vision of the Virgin Mary and then completing work on a fresco narrative of her life, the painter turns to the audience and asks, “Why complete a work of art when it is so beautiful simply to dream of it?”

The intense pleasure of a beautiful dream, the play of anticipatory fantasy, the arduous labor of planning and executing a project as complex as making a feature film, the frequent anxiety and frustration of working with large, mostly nonprofessional casts, often on locations remote from film studios—all of these (as well as many other) emotional states are in play in the accounts about the making of Pasolini’s Arabian Nights. Like many of the episodes in the film itself, these affective states, and the actions and experiences to which they are responses, continually turn into each other—erotic dream into harsh reality; wrenching separation into blissful reunion; social lowliness into sovereignty and vice-versa: an enslaved young woman disguises herself as a man and becomes ruler of a desert city-state; but several of the princes in the film, after enduring searing experiences, trade their splendid robes for rags and take up the lives of wandering beggars. Young men mesmerized for a time by pleasure are recurrent focuses of the film, but some of the same young men are repeatedly shown struggling uncertainly down a dusty road or effortfully passing from one part of a strange city to another, often pursued by a mocking crowd of small boys. These young men are regularly shown experiencing intense pleasures, including erotic pleasures, but they are just as often shown engaged in the hard labor of living. The most admirable of these characters embrace erotic pleasure when it makes itself available, but in keeping with those recurrent images of Pasolini nearly dancing for joy on the sets of his films, their libidos overflow into other pursuits and projects that others might see as repellently and unenviably difficult.

For Pasolini, between “simply” dreaming of a work of art and completing it, there were innumerable steps and a very long series of challenging yet potentially enjoyable interactions with the people who lived in the locales he often traveled long distances to film. Many times, as soon his latest film opened, he was brought up on charges—of obscenity, of blasphemy, of outraging public decency—and his successive trials were at times no doubt painfully stressful for him. But in his unflagging (some would say increasing) willingness to challenge the legal and social limits of expression, one may see yet another kind of libidinal investment in a laborious and recurrent struggle.

In thinking of the many steps between “dreaming up” a film and completing work on it, we can question whether a work like Arabian Nights may be “finished,” given how open its form is, not least for first-time viewers, who may be initially bewildered by the director-storyteller’s penchant for shifting back and forth between narratives, locales, and groups of characters. Pasolini’s intensification of the director’s involvement in the production process began long before the making of the film commenced. Other directors might send out a scout or two during the preliminary phases of planning to investigate possible locations, but Pasolini was committed to doing his own location-scouting. On these treks, he was often accompanied by a close friend or two, such as his fellow writers Alberto Moravio and Elsa Morante, who traveled with him through India, or Ninetto Davoli, a young Calabrian man with whom Pasolini, at forty, had formed an intimate relationship when Davoli was fifteen. Pasolini went on to feature young Davoli in nine of his films, including a key role in Arabian Nights. (Pasolini co-authored the screenplay for the film in collaboration with feminist novelist Dacia Maraini.) Davoli said in a recent interview that Pasolini had told him tales from The Arabian Nights as bedtime stories during an earlier location-scouting trip that the two had taken, and that after the director had told him many of the tales, their “pillow talk” had turned for a succession of nights to the question of which ones should be included in the film (Guillen 2013).

Many critics have observed that one of Pasolini’s most radical interventions in his cinematic retelling of The Arabian Nights was to drop the narrative’s main framing device, the character of Scheherazade, whose situation traditionally impels the telling of the tales; that is, the young woman’s need to keep her tyrannical and murderous ruler of a husband from having her executed (as with previous brides). She does so by continually deferring the outcome of the stories she tells him every night until, after a thousand and one nights of “to-be-continued” narration, he has learned to love and trust her. But if we are aware of Pasolini’s particular way of making films, and if we know something about the backstory leading up to the making of Arabian Nights, we can see that the Scheherazade function is not missing: it has simply been displaced into the preparations for the making of the film, which for Pasolini were an integral part of the film itself.

With this in mind, one might say that in entertaining his beloved Davoli with the tales in bed night after night and discussing with him the daunting question of which and what aspects of those tales might make the best film, Pasolini himself took on the role of Scheherazade (not unlike his casting of himself in the key role of spokesman for the artist Giotto in The Decameron). But the outcome of Pasolini’s telling of the tales did not have the binding force that Scheherazade’s eventually did. Davoli had already informed Pasolini in the course of the making of The Canterbury Tales that he had decided to marry and have a family. He wanted to stop acting in films and resume the carpentry trade that he had been learning when Pasolini had entered and transformed his life a decade before. Davoli had first been the director’s lover; he stayed on to become perhaps his most intimate and dependable friend. By the time he told Pasolini that he was in the process of forming a new primary relationship, Davoli had been serving as the director’s alter ego for many years. For Pasolini, Davoli had also been making physically and emotionally available in a single person the spirit of the boys and young men of the borgate, the sprawling underclass neighborhoods on the outskirts of post-war Rome. This is where Pasolini’s admired and beloved ragazzi di vita (literally “boys of life,” the title of his first novel, 1956) pursued their often punishingly difficult but (as Pasolini saw it) also fundamentally joyful and sexy lives in defiance of an increasingly rigid and pervasive bourgeois worldview. Pasolini felt that Davoli’s companionship kept him close not only to a youthful stage of life that he had already left behind, but to an entire social class of young men whom Pasolini hoped would play a crucial role in resisting mainstream attitudes toward sex and work.

Shortly after finishing filming Arabian Nights and thereby completing his Trilogy of Life series, Pasolini’s despair over the erotic-utopian political project that the three films represented to him led him to publish a repudiation. Before and during the making of Arabian Nights, he appears to have experienced his own despondency as largely a personal one, a response to the loss of his primary relationship with Ninetto Davoli. Biographer Barth David Schwartz quotes Pasolini describing himself in a letter to a friend as being “insane with grief” over losing Davoli (1992, 587). According to his friend Enzo Siciliano, Pasolini wrote a sequence of more than a hundred sonnets modeled on Shakespeare’s in which Davoli figures as a “terrible Lord,” and the poet enacts feelings of anguish, betrayal, and abjection as a “burned-out” lover “inveterately masturbat[ing]” onto sweaty sheets (1982, 339). It may have been during location-scouting travels for The Canterbury Tales that the director fell into the habit of telling Davoli tales from The Arabian Nights as bedtime stories. We know that did not happen during Pasolini’s travels before the making of the film itself, for he had scheduled those for January 1973 so that during the month when Davoli was married, Pasolini was far away from their native Italy.

Pasolini professed to be unable to imagine a role for Davoli in the nightmarish world of Salò (1975), the last film he completed. He could imagine no place for the joyful form of living that Davoli represented to him in a film about the kinds of relations of fascistic domination that were far from having been a monopoly of the followers of Hitler and Mussolini. Pasolini came to believe, late in his life, that such relations pervaded much of contemporary life under the nearly universal imposition of consumer capitalism on populations all over the world.

Yet, after his marriage, Davoli did not disappear from the director’s life. Indeed, Pasolini spent what turned out to be the last evening of his life (at the beginning of November 1975) with Davoli and the younger man’s family. The next day, the authorities sent for Davoli to make the official identification of Pasolini’s battered corpse. At the time he made Arabian Nights, Pasolini felt a richly contradictory set of intense feelings for Davoli and about the end of what may have been his most sustained and sustaining intimate relationship. Pasolini’s investment in all facets of his work was complex—from recruiting attractive young men to perform in the films to withstanding the legal and political challenges with which the films were routinely greeted. This may help us to understand how Pasolini managed to persist not only in working with Davoli, but how he drew on the confusion, anguish, and excruciating feelings of sexual jealousy and betrayal that the breakup had caused him to help Davoli craft his performance as one of the most intriguing figures in the film, the protagonist of the highly enigmatic tale “Aziz and Aziza.” It is at once perhaps the most troubling of all the narratives that Pasolini chose to retell and quite possibly also the most weirdly and gravely comical. Some signs of the intensity of Pasolini and Davoli’s connection and the pressures on both of them are apparent in the extremity with which Pasolini tells this particular tale, which he presents in a long and (for this film) uncharacteristically continuous half-hour rendition placed at the temporal center and at the very narrative heart of his Arabian Nights.

Aziz and Aziza

Despite the close resemblance of their names, the two characters are extremely different from one another: Aziz appears to be a heedless young man out for a good time, blithely unaware of the emotional storms that rage around him, while the young woman Aziza is an emblem of utterly selfless devotion who continues to promote the happiness of unfaithful Aziz even as she wastes away with unfulfilled longing for his love. In the film, the story of Aziz and Aziza is nested within two longer narratives of enduring erotic love that are ultimately fulfilled. The first of these involves Zumurrud, a young slave who escapes, disguises herself as a man, becomes king, and is eventually reunited with her young lover Nureddin. The other is about princess Dunya, who starts out distrusting all men, but learns to trust at least one, Prince Taji, who shows her unstinting and understanding devotion. Taji’s tale parallels the main story of the usual frame-narrative of The Arabian Nights, with the genders of the protagonists reversed, in which Scheherazade gradually wins over her initially hostile and distrustful husband. These two narratives, of Zumurrud and Dunya, are each initiated, interrupted, and resumed several times in the course of the film. They are the main chains on which the rest of the narratives are strung, with the central Aziz and Aziza story set as a kind of unlikely, even grotesque, jewel at their narrative intersection. This tale contrasts harshly with the other two: rather than being a story of ultimately fulfilled desire, it tells how Aziz neglects the woman who loves him, marries a woman he doesn’t love, and pursues the love of yet a third woman who is said to be “mad” and who eventually has him castrated.

Aziz and Aziza (their story runs from Nights 111 to 128 of the 1,001 in Malcolm Lyons’s 2010 translation of The Arabian Nights) grow up in the same household. Their fathers are friends and determined to marry their offspring to each other. In its early sections, the tale of Aziz and Aziza could be seen as an earlier version of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, in which two youngsters brought up in the same household develop loving feelings toward each other that can find no recognizable form in their milieu. In this tale, Aziz and Aziza grow up (like Cathy Earnshaw and Heathcliff) in close proximity. They are as intimate as siblings may be, even sharing a bed, but in their case, early intimacy produces entirely different outcomes in their feelings toward each other. As they reach marriageable age, Aziza sustains an entirely selfless and abiding desire for Aziz and for his happiness, while Aziz cloddishly declines not only to return Aziza’s love, but even to recognize its existence until he is forced to do so by extreme circumstances after her death.

When the long-awaited day of the wedding arrives, Aziz fails to appear for the festivities. While wandering through the city, he has become enthralled by a mysterious and beautiful young woman who has appeared at a high window. Without s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Synopsis

- Credits

- Chapter One: Pasolini Scheherazade

- Chapter Two: Bare Life

- Chapter Three: Pasolinian Comedy

- References

- Filmography

- Index

- About the Author

- About the Editors