eBook - ePub

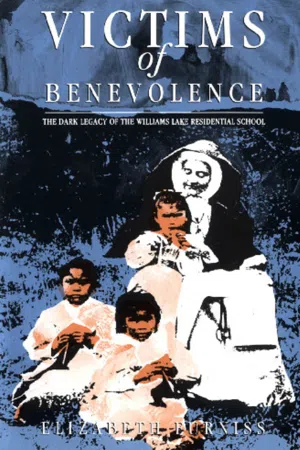

Victims of Benevolence

The Dark Legacy of the Williams Lake Residential School

- 142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An unsettling study of two tragic events at an Indian residential school in British Columbia which serve as a microcosm of the profound impact the residential school system had on Aboriginal communities in Canada throughout this century. The book's focal points are the death of a runaway boy and the suicide of another while they were students at the Williams Lake Indian Residential School during the early part of this century. Embedded in these stories is the complex relationship between the Department of Indian Affairs, the Oblates, and the Aboriginal communities that in turn has influenced relations between government, church, and Aboriginals today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Victims of Benevolence by Elizabeth Furniss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Estudios de nativos americanos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

A “Sacred Duty”: Christianity, Civilization, and Indian Education

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT the first three decades in the life of an Indian residential school in the central interior of British Columbia. It is about a dream shared by the Roman Catholic missionaries and the Canadian government: to see Native people, through residential schooling, abandon their cultural heritage and their nomadic hunting and fishing lifestyle, and adopt the presumably civilized ways of Europeans. With Native people living as whites, wearing European dress, speaking the English language, and working as farmers or labourers within the colonial economy, the “Indian problem,” government and church agents believed, would no longer exist: Indians would meld seamlessly into the mainstream society.

It was a grandiose and fatal plan, and as the Oblates of St. Joseph’s Mission soon were to find, one not easily accomplished. The Shuswap people of the Williams Lake area accepted the Roman Catholic missionaries and the residential school program only reluctantly. Throughout the first thirty years of the school’s operation, Native people, at times indirectly, at other times openly and vigorously, struggled against the assimilation plan, the residential school program, and the Oblates’ control over their children’s lives. These simmering tensions between the Native population, church agents, and government officials were drawn to a head by the tragic deaths of two young students at the Mission school, one in 1902, the other in 1920.

The first death was that of Duncan Sticks. Born in 1893 to the family of Johnny Sticks of Alkali Lake, Duncan had been taken to the Indian residential school near Williams Lake at an early age. He was unhappy at the school, and on a February afternoon in 1902, Duncan and eight other boys ran away. While the other boys eventually were captured and returned to the school, Duncan disappeared into the forest. His body was found the next day by a local rancher; Duncan had died by the roadside thirteen kilometers from the school.

The second death was that of a young boy named Augustine Allan from Canim Lake. Augustine committed suicide while at the residential school in the summer of 1920. He and eight other boys had made a suicide pact and had gathered together to eat poisonous water hemlock. Augustine died, but the other eight survived.

The deaths of these two boys raised many important questions and drew critical public scrutiny to the plight of students at the Mission. Why did these boys die? What was happening at the school? Why were children running away, or attempting suicide?

The early history of the St. Joseph’s Mission school, and the deaths of Duncan Sticks and Augustine Allan, are re-counted in the following pages. These stories are told here in the belief that they evoke issues that are essential to an understanding of contemporary discussions of the Indian residential schools and their impact on First Nations in Canada.1 Yet this is not simply the story of the deaths of two young boys, or even of the Indian residential school system. More importantly, the events portrayed in this book reveal how the long-term structural relationship between First Nations and the Canadian government, and the beliefs that have legitimized this relationship, have had tragic consequences for innocent people.

COLONIAL POLICY AND THE IMAGE OF THE INDIAN

Indian residential schools were the product of the nineteenth-century federal policy of assimilation. To understand how and why this policy was created, we must look deeper into the history of Indian-white relations, and to the beliefs that Europeans have held about Indian people since the Europeans’ first arrival in North America.

Over the last four centuries, two fundamental assumptions have characterized the dominant attitudes held by Europeans towards Indians in North America. First, Europeans have presumed their society to be inherently superior to that of Native peoples, not only in terms of technology but in terms of moral, intellectual, and artistic development. Native peoples have been perceived not as existing in complex societies, having their own systems of government, their own social and political institutions, and their own highly-developed technologies and intellectual and artistic traditions, but as a child-like, savage race, having only a rudimentary degree of social organization, living a precarious, hand-to-mouth existence, and adhering to superstitious, pagan beliefs. Second, following this premise of superiority, Europeans have taken it upon themselves, to varying degrees in different historical periods, to transform Native peoples, both physically and culturally, into an image more acceptable to European sensibilities. This effort has been legitimized by a fundamental conviction that Native people require the guidance of Europeans to live successful lives, and that European intervention in Native peoples’ lives, even when forcefully applied, is ultimately in Native peoples’ ‘best interests.’

Of all groups within colonial society, Christian missionaries have been the most consistent in adopting roles of paternalistic benefactors to Native communities, and in seeking to transform Indians into European ideals. The impulse to convert people to the Christian faith was not unique to missionary relations with North American Native peoples. From its inception Christianity has been an evangelical movement, driven by Jesus’ final words of advice to his disciples: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you.”2 The belief that the salvation of one’s soul depended on the acceptance of Christian faith, and that the second coming of Christ would occur only when the gospel had spread through the world, were common long before European arrival in North America.3 Armed with these convictions, the first missionaries to arrive on the shores of New France in the seventeenth century imagined the New World as an untouched territory, one ripe for the missionary teachings and one in which they could prove their devotion to their faith through their heroic self-sacrifice.

From the outset, and with the full support of both the French monarchy and its colonial officials, the Roman Catholic missionaries to New France saw their task as not only to Christianize, but to civilize Native peoples into the dress, language, and habits of French culture.4 By the early 1600s Jesuit and Recollet missionaries had begun to preach the gospel to the Micmac, Montagnais, Algonquin, and Huron nations in a territory stretching from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Georgian Bay. The education of Natives in churchrun schools, where feasible, was a central component of the missionary plan. By the 1630s the Jesuits had built a residential school for Huron children at Quebec City, and had established a mission where they were encouraging the nearby Montagnais to settle into agricultural villages.5

With the fall of New France and the establishment of British sovereignty in the next century, a path was cleared for the expansion of other Christian denominations, notably Anglican and Methodist, into Upper Canada. In the following decades Anglican, Methodist, and Roman Catholic missionaries spread further westward and northward across the continent, competing amongst each other for influence and favour among the various Native nations. By the mid-1800s most regions of Canada had been claimed by particular religious denominations. In British Columbia, Roman Catholic missions were established throughout the interior, while Anglican and Methodist missionaries vied for territory on the northern coast. All three denominations, and the Presbyterian church, were active in the more heavily settled regions on the south coast and Vancouver Island.

Not all groups within colonial society had the same motives for entering into relationships with Native peoples, nor did they always share the same vision of how Native people should live their lives. The political and economic interests of fur traders, settlers, and government officials at times complemented, and at times conflicted with, the missionary - program. For example, missionaries and fur traders often worked closely together. Missionaries typically arrived in new territories with the fur brigades, and depended heavily on company employees for food, assistance, and introductions to the Native nations. While fur traders shared the prevalent beliefs of the time about the primitiveness of Native cultures, they were willing to tolerate what they saw as barbaric customs and practices in order to maintain good business relations. The success of the fur trade was conditional on Native people continuing to occupy their lands and practice their traditional pursuits of hunting, fishing, and trapping. Further, traders perceived disruptions to the integrity of Native communities to be potential threats to the continued success of the enterprise. Because of these conflicting interests and their dependence on the fur traders, missionaries at times were forced to temper the civilizing component of their mandate.6

For their part, government officials ultimately were concerned with maintaining their authority within the colonies, with ensuring the safety of settlers, and with facilitating the expansion of an agricultural and industrial economy. Through the 17th and 18th centuries Native nations played critical roles as military allies in the wars between the British and the French. For the sake of maintaining these strategic alliances, colonial administrators were reluctant to interfere too drastically in the lives of Native peoples and communities. As a result, for much of the period leading up to Canadian confederation, both the French and later the British colonial governments followed a general policy of conciliation towards aboriginal peoples.7 In practice, this policy translated into a variety of initiatives for relating to Native nations, initiatives that were shaped by local conditions and pragmatic concerns.8 Government agents were content with allowing missionaries to assume the role of front line agents of paternalism. Missionary endeavours were supported, both financially and morally, as long as they were received favourably by the Native communities and did not incite radical social change.9

With the establishment of British colonial authority in 1760, the conclusion of the War of 1812, and the rapid expansion of white settlement westward, Indian-European relations shifted from ones of strategic partnership to ones of direct, open competition for land and resources. Indians now were viewed as obstacles to the country’s development. In regions of intense Indian-white conflicts over land, settlers began to generate racist discourses and calls for government assistance in suppressing the Indian populations. In the most heavily settled regions, Native populations were becoming destitute and overwhelmed by the effects of epidemics, social upheaval, and economic dislocation from their traditional lands. Where Indians were no longer perceived as a threat, the settler population could afford feelings of sympathy; the hostile savage image gave way to the image of the Indian as the noble savage to be pitied and protected. This image gained widespread popularity among the Canadian public in the first half of the 1800s through the historical romances of Fennimore Cooper and the paintings of George Caitlin and Paul Kane, and through later travel narratives by such writers as William Francis Butler and George Grant, all of whom lamented the vanishing of the Indian race.10

Such concerns for the welfare of Native people were a reflection of a more general humanitarian ideology that arose through the social reform movements of the early 1800s in Britain and the U.S. The industrial revolution in Britain had brought with it a dislocation of the population from rural to urban centers as well as critical disparities in wealth between socio-economic classes. The low wages, bad working conditions, and urban ghettos in which many of the poor were forced to live became key issues through which liberal politicians, missionaries, and labour spokesmen launched their public critiques. Similar calls for social and economic reforms arose as the industrial economy expanded in the early 19th-century United States. These general public concerns with issues of poverty and social conditions were extended to the plight of Native Indians; public pressure in Canada began to be applied on missionaries and colonial officials to provide Native communities with aid and assistance.11

The intersection of political and economic interests, missionary ideology, and popular humanitarianism laid the foundation for the transformation of the policy of conciliation to a policy of civilization in Canada during the early 1800s. In contrast, British colonial officials now sought to directly intervene in Native communities and to encourage Natives to adopt the civilized practices and habits of European society. The first government-initiated civilization strategy was enacted in Upper Canada in the 1830s.12 With the collaboration of Methodist missionaries, a program was developed to establish permanent villages and schools where Natives would be settled and taught basic literacy, agricultural, and industrial trades, as well as principles of Christian morality and belief. The ultimate goal of this program was to create Christianized, civilized, and self-governing Native communities under the protection of the British government.13 The program had the additional benefit of ensuring that adjacent lands once occupied by Native peoples would now be free for white settlement.

Despite initial difficulties, over the next decades Methodist, Anglican, and Roman Catholic churches, with state support and funding, continued in their ventures to civilize Native populations. Education increasingly became viewed as the most effective means of bringing this about, and schools began to be established throughout the most heavily settled regions where Native peoples were most destitute. By the 1850s the program of civilization through education in church-run schools had been firmly entrenched in the missionary tradition throughout Canada.

Through the history of Indian-white relations in Canada, Native peoples have sought to mold and manipulate their relationships with missionaries, fur traders, and government agents in order to advance their own interests. In many regions Native peoples initially supported the establishment of missionary-run schools, believing that a knowledge of the English language and agricultural and trade skills would enhance their opportunities, while at the same time enabling them to maintain their communities and their traditional cultures in their changing economic circumstances. This had been the hope of the Native nations of Upper Canada when the first industrial schools had been established in the 1830s. Yet by the 1860s support for Christianity and mission education in Upper Canada was diminishing, as tribal councils rejected the mission program as one geared to dividing their communities and dismantling their cultures.14

As Native resistance mounted, missionaries and government agents began to adopt more coercive measures to encourage the civilization of Native peoples. The paternalistic presumption that missionaries and government agents had long used to justify their relationships with Native people—that they were working in Natives’ ‘best interests’—now began to be expressed through the creation of a coercive federal Indian policy which sought not only to civilize, but to forcibly assimilate Indians into the dominant, Euro-Canadian society.15

FEDERAL INDIAN POLICY

In 1867 the federal government of Canada, through the terms of the British North America Act, took on the official responsibility for managing Indians and Indian lands. Native people continued to be seen by Euro-Canadians as a child-like, primitive, and inferior race. These assumptions now were encoded in legislation, as Native peoples were legally defined as non-citizens and wards of the state. Federal Indian policy explicitly sought to protect Native peoples in isolated reserve communities, where they would be sheltered from white encroachment and from the immoral influences of the rougher side of white frontier culture, and where Indians could be subject to government efforts to steer them into a process of cultural change. Existing Indian laws in 1876 were consolidated into legislation known as the Indian Act, which provided government representatives with sweeping powers to control and direct virtually every aspect of Native lives.

By 1880 a separate government agency, later known as the Department of Indian Affairs, was set up to administer federal Indian policy.16 The highest position within the bureaucracy was the office of the Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, stationed in Ottawa, and presided over by an elected Membe...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter One A “Sacred Duty”

- Chapter Two The Shuswap Response to Colonialism

- Chapter Three The Early Years of the Mission School

- Chapter Four A Death and an Inquest

- Chapter Five The Government Investigation

- Chapter Six Runaways and a Suicide

- Chapter Seven History in the Present

- Appendix

- Notes

- Index