- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

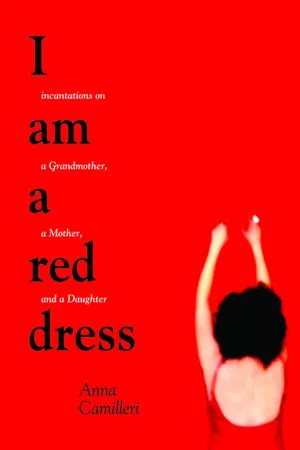

Yes, you can access I Am a Red Dress by Anna Camilleri in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Daughter

I went to where the wind lives –

I put my ear there.

I went down below.

Where the wind lives is chaos;

what the wind does is blow.

Lexicon of the Red Dress, part 3

Like a string of goslings, my grade two classmates and I were marched off to St Nicholas of Bari Church for our first confession. We sat in hard wooden pews in the dim light, fidgeting and giggling while we each waited for our turn in the confessional – our teacher’s finger pressed tight against her lips, shushing us. When it was my turn, a man I knew to call Father motioned me to follow. He wore a long brown robe and his hair parted sharply at the side. I stepped inside the room and the Father closed the door behind me. The room was empty except for two rust-coloured, vinyl chairs. He sat down across from me. “Do you have any sins to confess, my child?” he asked.

Sin, as I understood it, meant my badness. We had been taught that confessing our sins would wash them away, except for Original Sin. “I didn’t listen to my mother,” I offered. “I hit my brother. I didn’t do my math homework, and I failed the test.”

“Do you have any other sins to confess?”

I blinked back at him. “No, Father, I don’t think so.” I looked down uncomfortably. “I could be better, I could pray more.” I hoped my words would satisfy him.

“Do you ever touch yourself?”

I fidgeted in my seat and shook my head.

“Do you ever let anyone touch you, down there?”

Did he see what was in my heart? I tried to wipe my mind clean, but images of my grandfather – his hands on me, stubble rough against my skin – flickered behind my eyes, and I heard his words: If you ever tell anyone, I will take you to the hospital and have you sewn up. You are nothing but an ugly, dirty girl. I folded my hands, tried to look honest, and replied to the priest my best level, “No.”

“Do you ever look at picture books – dirty magazines? Do you ever touch yourself?” I was sure that the priest was no messenger from God and that I needed to get out of the room as quickly as possible. I pulled my braid around and twisted it nervously.

“No,” I said. He slumped into his seat with disappointment.

I rejoined my classmates, thankful for the dimness. I was no stranger to hateful words, or my belly turning itself inside out. Priest or not, he was nothing new. I made my own covenant with God. I promised God I would hold onto to myself as best I could, until I could wrest myself free. I didn’t believe that horrible things were an act of God. I believed in right and wrong and that people do bad things because it’s what they have chosen.

Some things have no place in this world. Some things deserve to be sent out of this world, or at the very least, put back to where they came from. That priest, saying the things he said to me, was wrong, and my grandfather’s hands had no business with my body.

The shame that I carried around with me was not mine to own. I wanted to return it to its rightful place. My grandfather would have had me believe that his behaviour was inspired by an inherent unlovable quality in me, but I had done nothing to deserve what he had done.

After hearing my mother say a hundred times over, when your grandfather dies I’m going to the funeral in a red dress, I conjured her, the woman in the red dress, her hair the colour of night. When I was hurting, I wondered what she would do in my place. She became a muse in my life, as real as anything – an angel, a siren, shining a light in the dark corners of my soul, insisting it is possible to live without leaving myself behind, that more than it being possible, it is necessary. It was she who started me thinking it was not enough to only get by, to try to make peace with events that are not reconcilable.

When I was thirteen, I made a promise to myself that has radically changed the course of my life. I imagined the woman in a red dress, and I made a covenant, not with God, but with myself. I vowed that the violence that has been alive in my family for generations would end on my branch of the family tree; I would not surrender to it. I could not resign myself to believing that the violence I had lived would fade into the background of my life – that the passage of time would somehow miraculously heal me.

I worked in the violence-against-women-and-children movement in my late teens and early twenties. In downtown shelters and drop-in centres I prepared meals, interpreted mail for women who didn’t read English, and kept a straight face when it mattered by telling bold-faced lies (called advocacy work). It wasn’t uncommon for abusive husbands to file missing person’s reports, and for local police to call on their behalf, quoting details from the missing woman’s file. I often wanted to say, “What makes you think she’s missing? Maybe she left for a good reason.”

But I mostly listened and I often felt rocked. It was there that I learned that my story, while deeply personal, is much, much bigger than me. I am not alone; none of us – women and men – who have been raped, as children or as adults, is alone. Violence is cyclical, and any so-called incidence of violence is never isolated. I have spent years working to untangle myself from its monikers: denial, self-hate, shame, silence. I am sure that I will never be done. It’s the work of a lifetime. Sometimes many lifetimes.

My grandmother, my mother, and I – none of us were ever allowed to be children, not in the true sense of the word. Our lives are etched by immeasurable loss. Despite my experience, perhaps because of it, I try to live a life rooted in the values and principles I hold dear; I’ve committed myself to not forsaking my grandmother and my mother. Laying greater blame for the brutality I’ve experienced at the feet of the women in my family and then walking away from them would be untenable. They need my compassion, not my hate.

I am my mother’s first-born child, a daughter, and I can only imagine the covenant my mother made to keep herself safe.

My mother is my grandmother’s first-born child, a daughter, and I can only imagine the covenant my nonna made to keep herself safe.

I have wondered what it would have been like to live with a wolf; to have a wolf for a father, a wolf for a husband – a wolf who has an appetite for his own.

I have had a wolf for a grandfather, but I am not Little Red Riding Hood. I am a woman in a red dress, insisting it is possible to live without leaving oneself behind, insisting that it is necessary.

Incarnadine

Wind blows cool through the side door. From my place on the stage all I can see are smoke curls dancing in the light of the stage lamps overhead; the audience, an indiscernible echo. I hear laughter, whispers, and programs fanning sweat brows.

Words roll out of my mouth; the undertow pulls me away. Today my grandfather was sentenced to three years in a federal penitentiary. No, don’t think about that. I’ve wandered far from shore. The audience is a ship in the distance; I swim upstream like incarnadine salmon, break through the surface to the stage, the heat, my final words. I follow the applause off stage where the air is cooler, where there is room to breathe. Where I can swim without measuring distance.

Today my grandfather was sentenced to three years in a federal penitentiary. No, don’t think about that. Think about the list with sub-lists that waits on the desk. I’m moving back home to Toronto in ten days. Three thousand miles away. The garage sale is tomorrow, and I’m selling all of my things. How many times have I done this?

I’m an expert at packing, having moved more times that I can count. There was always a good reason to move – negligent landlords, crazy neighbours, expensive utilities, relationship break-ups, the need for a new view. There’s a rhythm to the ritual of sorting, packing, unpacking, like the moon’s cycle. Moving is not just an activity, it’s an art that requires the right tools: Xacto knife, packing tape, newspapers, rope, garbage bags, a multi-head screwdriver, Allen keys, waterproof markers in at least four colours, blankets, boxes (liquor store boxes work best), and most important of all, an organizing principle.

Do you want to pack by item, room, object size, most to least used? I like packing by room with an alternating pattern: three living room boxes, then three bedroom, one bathroom. I save the kitchen for last because it’s my favourite room to pack. Label your boxes. Colour code them if you’re visually oriented. Wading through twelve boxes to find latex gloves at three in the morning is not sexy.

I appreciate the weight of a full box. With each move, I discover forgotten letters and embarrassing photographs. Everything old is new again and everything new is old enough to be packed. Bare walls, a fresh start.

In my different locales, there have been many lovers, new neighbours, garage sales. Nobody asks me what I am running from. Nobody ever asks me if I am running from something. On crowded buses, when a stranger’s elbow is up under my chin, I ask myself this question, and I always come to the same answer: I’m running to, not from, and I hold fast like a swimmer gripping a raft. I swim some more. My stroke improves. I rest at the next island, dazzled by the view. It cycles like looped images, like the moon, like the seasons.

†

This morning I jumped out of bed before my lover was awake and began telling her about my dream, nudging her until her eyes were open and blinking.

“I’m sitting in a concrete yard, leaning against a fence, naked. You walk through the gate and hand me twelve smooth, whittled branches and a sea sponge. You’re dressed in army fatigues. In a very business-like manner, you tell me to put the sponge inside my cunt and then to embed the branches. You explain that in case of rape, the bastard will get pricked, pull out, and run away bleeding. I spread my legs, insert the sponge and branches, and whistle into the traffic. No one notices my lack of clothing, not even you.”

She sits upright and touches my face gently, distressed. “It’s a good dream,” I explain. “I’m not scared. I didn’t wake up shaking.”

When I was a kid, I had nightmares about hooded men banging at my bedroom door. I always woke just before the door was kicked through, in a cold sweat and a puddle of warm piss – my limbs stiff as a board. Sometimes I dreamt about hundreds of rats teeming, gnawing at the walls. I couldn’t stand up. I lay in bed, looking up at the ceiling. The dreams hovered around the light fixture, waiting until nightfall to descend like mosquitoes. Until my breath slowed. Until I was limp and my body freshly pressed with sheet. Until my lips parted. Waiting, until I looked like a babe in a crib. Then the dreams came down like rain. Drip, drop.

†

I stopped wetting my bed when I was sixteen years old. I’d had enough of soggy sheets, and I went to see my doctor who told me I had enuresis, a common condition that is caused by emotional trauma or a physiological problem. He asked if anything traumatic happened to me when I started bed-wetting. I said no, then yes. Then the words spilled out: “My grandfather touched me.” My body folded at the waist, and the room spun. I held onto my tears, straightened up, and looked at him. He leaned forward, his face screwed up in an empathetic expression.

But I didn’t want his kindness. I wanted to get away from those words, and from myself. I gathered my bag and darted out of his office. I walked aimlessly through the city, convinced that everyone in the world had heard me. When I arrived home, my mother asked where I’d been. Nowhere – I said nowhere.

I stopped dreaming about hooded men and rats after I filed sexual assault charges against my grandfather. Now, I dream about whistling kettles, kinetic sculpture, and swimming in the Mediterranean.

I first contemplated filing charges when I was twenty years old, but I wasn’t ready to speak the details out loud. Four years later, I visited Toronto and took a walk through the neighbourhood I grew up in, looking for answers. I arrived at my grandparents’ house, the house where it all happened. Apart from some minor exterior renovation, the house was preserved, as in my memory. I wanted to open the door, run into Nonna’s strong arms, to burrow into the space between her ear and collarbone and savour the sweet scent of her skin. But I couldn’t bring myself to cross the street. I couldn’t run to her. Our reunion would come to an abrupt end, and silence would follow.

My grandmother knew what her husband had done to me, and she had let my body fall to the ground like autumn leaves. Those leaves, slippery, brown, and rotting, I could not cross.

†

A year later, at the age of twenty-five, I filed a sexual assault victim impact statement with the Vancouver Sexual Assault Squad. I spent two hours with a plainclothes officer in a small room, a dictaphone next to a pink and yellow plastic flower arrangement, tape heads spinning. The questions were endless:

“Now, we don’t want to put words in your mouth, but we need to be able to pass information on to the Metro Toronto police. Exactly what type of assault occurred? What happened? How old were you? This occurred more than once? Exactly what occurred? Do you need a break? Do your parents know? Do you have any brothers or sisters? Do you need a break? If your grandfather were here today, what would you say to him? How do you feel? Why did you wait until now to file charges? What do you want to happen as a result of this statement? Are you employed?”

My answers were long winded, all over the map. What was the question, I asked repeatedly. What was the question? When the officer offered breaks, I didn’t accept. I’m not sure that I would have returned, and I didn’t want to carry the weight of this story any longer. I wanted to scream: What do you mean by that? Isn’t it obvious why I didn’t jump up ten years ago to come and tell you about everything that’s nauseated me for my whole fucking life? You want answers? Yeah, I have a job. I was raped by my grandfather. No, I haven’t forgotten a fucking thing. I have a colour picture album. He stunk of tobacco, cheap wine, brilliantine, Old Spice. He threw my underwear clear across the room. I was five years old when he started messing with me. Still had my baby teeth. He used to talk through the whole damn thing. I don’t know what was worse – the talking or the. . . . Hesaid that everyone would think I was a dirty girl if I ever said a word. When he was done, he’d spit into his palms and press the loose hairs back into his pompadour. If my grandfather were here, I would spit in his face. Then, I would tell him there’s a bill to pay – he needs to account for what he did. Once? Seven years, times fifty weeks a year at an average of two assaults a week, equals seven hundred and twenty-eight. I haven’t eaten out in restaurants that many times. I haven’t seen seven hundred films. I don’t want to believe it.

But I didn’t unleash my anger at the officer. He’s not the man who hurt me.

I signed forms to have documents released, spoke with the investigating officer three times a week. I began to feel afraid while having sex, and then I stopped having sex altogether for several months – my body frayed with memories.

Those months stretched out like a cracked prairie highway, September indistinguishable from April. The prairie...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Prologue

- Grandmother

- Mother

- Daughter

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Publication and Performance Notes

- About the Author