- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Law of Desire by José Quiroga in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE: THE SUMMER BEGINS

The story should always be evolving no matter what.

In Law of Desire, there is a constant sense of development. Almodóvar has remarked that “the story should always be evolving no matter what, even by means of the title sequence, if that is possible” (Bouza Vidal 1988, 206). The film mixes homosexual love and trauma, transgendered politics and identity, and combines them with a murder of passion investigated by two detectives who seem to have appeared out of a film noir. It works by means of displacement and deferral, exchanging one plot line for another: a tale of artistic impasse becomes a love story which, in turn, is displaced by the narrative of a family trauma, and all of these yield to the plot line of a thriller. The triad of desire formed by Pablo, Antonio, and Juan is complicated by the very complications of life and art: desire is grounded upon issues pertaining to reality and the imagination, but it is also embedded within what Freud called the “family romance,” or the webs of desire created within the family structure. These are not merely stored in the past and in memory, but keep returning and imposing themselves upon the present. For Almodóvar, desire is a text of unknown authorship, and we are all simply following scripts given to us by some invisible and unreachable directorial figure. Desire is a fully codified text—it has its own system and its own laws. Almodóvar implies, in this film, that we pretend not to know this, because we need the illusion of freedom for the sake of social existence. And he warns us that the price we pay for this illusion is too high.

Every Almodóvar fan knows that the title sequences in his films are exquisitely created in order to establish the mood and the tenor of the film itself. This was particularly evident in Women on the Verge, and grew in complexity in Hable con ella (Talk to Her, 2002), La mala educación (Bad Education, 2004), and Volver (2004). Law of Desire opens in silence, with merely the shuffling of rumpled pages on which a typewritten font displays, first of all, El Deseo S.A., the production company created in order to finance the film (and which still finances all of Almodóvar’s films under the direction of Agustín Almodóvar, the filmmaker’s brother; many of the technical collaborators that appear in Law also still work with Almodóvar to this day).

Almodóvar could have benefited in the 1980s from what was called the Ley (Law) Miró, named in honor of Pilar Miró, who was then Spain’s Director General of Cinematography. 2 This was the law that totally revamped the way films were done in Spain by helping in the production and funding of new films and fostering new talent. Nevertheless, Almodóvar said they did not receive help from the Ley Miró for this particular film, and Almodóvar and his brother Agustín had enormous difficulties in securing financial backing for it (Strauss 1996).3

In the very opening credits of Law of Desire, we are meant to focus on the materiality of writing by seeing the typed pages illuminated by a white oval of light. We begin, thus, with paper as a point of origin and within a very constructed mise en scéne, one in which the volume of the rustling of pa per has been jacked up. The light shines on the page as if the page itself were its own theater. The music we hear at first is dramatic, pulsating, and it gives an ominous feel to this initial sequence. It is the opening of the second movement of the popular Symphony no. 10 by Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich—the symphony that marked Shostakovich’s slow and progressive rehabilitation after the difficulties he encountered under Stalin, when his work was banned and denounced as “formalist.” The second movement, which Almodóvar uses here, is deliriously orgiastic, symphonic, and even almost comical—it will also be totally different from all the other music used in the film. The story of the symphony in itself is not without relevance, as Shostakovich presented it the year of Stalin’s death, and the parallels with the end of the Franco era are obvious. The title sequence is almost minimalist, playing with the viewer’s expectations of what will come. There is a play on surfaces that refers back to the typewriter (an important object in the film), because of the rumpled sheet of paper, and the mechanical continuity of the machine and the music. Something chases after something else in a frenzied atmosphere of expectation. One could be tempted to think that the chase in the music refers to the chase of one lover after another (and certainly that fits, within the structure of the tale) or to a kind of obsessive compulsion. In my wildest moments, I have thought that it also refers to the way in which gender is chased by sexuality, or the other way around—to the way in which gender and sexuality operate as a kind of mutual chase of affection and flight. The end of the music leads to an abrupt switch. We cut to a room, and this cut in itself gives the title sequence a kind of “unfinished” feel, as if something were missing. Indeed, what we are missing, and what we are expecting, is to be shown the title of the film in itself. It will not come now, but rather at a later, more dramatic moment.

Sit down and start undressing.

The establishing shot of the bedroom is pretty static, compared to the music that has preceded it. This frozen frame is but an opening salvo for a film that will be shocking from its very first scenes. It is a room with a fan and a white wall on which a number of different paintings are hung—most significantly the picture of a Spanish lady on the back wall, establishing a “Spanish” cultural framework. The sheets are undone (just as the paper in the credits was rumpled), a shirt hangs next to the mirror, and the sunlight streams in from the left of the frame. A voice off-camera speaks to a man, whom I shall call an ephebe because he is young, practically hairless, and objectified as simply a figure of desire, an emblem of aesthetic beauty. He is dressed very simply, in jeans and a white T-shirt. The disembodied voice gives him instructions, and tells him to “sit down and start undressing.” The voice tells the ephebe that there is no hurry, orders him to keep his underwear on and, most importantly, insists, “Don’t look at me.” The voice then mentions the mirror to his left, and tells the ephebe that he should get up and go over to it. Once the boy is in front of the mirror, the voice instructs him to kiss his own lips (the handsome man in the frame is somewhat hesitant at this point), and then to rub “your own cock against the glass” before going back to bed. This is not an S/M scene—there will be one other, somewhat comical reference to S/M in the film—nor is it one that involves self-debasement, but rather the exercise of control in order to experience the vicarious pleasure of self-love. It is this kind of self-love that produces some of the more hesitant moments acted out by the young man, as if what was perverse and prohibited is this kind of forced narcissism and voluptuousness.

FIGURE 2. A voice off-camera speaks to a young man … an emblem of aesthetic beauty. DVD still.

The voice then guides the ephebe to play out a masturbatory scene, telling him to “play your fingertips over your body” and then to “take your cock and caress it over the underwear.” There is a dilatory tempo here: it is not a question of simple release, but rather of enjoyment. As the camera moves to shoot the boy from above (which underscores the overall notion of command and submission), the voice then tells the ephebe to take off his underwear, instructs him as to how he feels (“You’re getting more turned on”), and tells him to beg to be fucked. The possibility of penetration stops the performance of self-love, as the young man turns around and asks, “Hadn’t we agreed?” as if being penetrated were not part of the deal (that there had been a deal is now obvious); that rules had been set and that, in some way, they are now being broken. Almodóvar has mentioned how difficult it is for men to express a desire for penetration: “A man, who knows that he can be penetrated, never verbalizes this desire” (Bouza Vidal 1988, 208).4 At this point, Almodóvar is certainly making a point about the taboos of masculinity. In fact, this initial scene insists on breaking down these barriers, and in many ways it prepares the viewers for the kinds of male behaviors that will be presented in the film. It takes repeated viewings to realize that there is something strange about the young man’s voice: it does not seem to come from his lips, but from somewhere else.

Cut to an older man with glasses and a goatee reading from a script. After we see him say “fuck me” (in Spanish it’s fóllame), the camera cuts to a shorter, heavier, balding man, also repeating, “fuck me,” so that the repeated command disorients the viewer as to precisely who and when the words are uttered. This is the voice that we heard from the lips of the young man, and it’s clearly not his own. The resistance to penetration that Almodóvar talked about is underscored by means of the cut outside the scene—an “out-of-narrative” experience where it is someone else who is actually uttering those words. This composition outside of the room, moreover, allows the narrative as a whole to come together by also deflating its pretensions, revealing it as a comedy. Every time this scene has played at any of the venues where I’ve seen the film, the audience’s laughter manages to drown the script that is being read at the moment. The humor is in the disjunction between the scene and voice, both of them taking place on a different plane. The man dubbing the voice of the ephebe starts sweating and wiping the sweat off his brow with a white handkerchief—perhaps the most ridiculous and comic object in this whole composition. As his moans lead toward orgasm, the distance between action and voice is erased. While the almost clinical voicing of a very precise set of instructions produces the distancing effect, self-pleasure brings all of the elements into a composite whole.

Almodóvar has layered many elements onto this scene, like multiple arrows shooting in different directions. He deals here with the disjunction of voice and body, but also with the difficulties involved in seeing and participating. The scene portrays issues relating to scripted scenarios of love while also commenting on the way in which film manages to create and, at the same time, break the illusion of presence. In addition an element of biographical layering is also involved here. Part of Almodóvar’s own urban legend is that his first Super-8 films were so low budget that they had no sound, so he showed them while doing all of the voices himself (Strauss 1996, 2). Almodóvar asks us to question what we see, and he demarcates the thresholds between cinema and life—an important theme in Law of Desire . As in Bad Education, one of the main narrative axes of this film concerns the complications that ensue with a script where art and life are confused. There are scripts that need to be read and there are scripts that need to be followed, and, then again, there are scripts that should not be written at all. There is a scripted quality to the actions of a body: the voice addressing the young man reads from a script, following the scripted scenarios of another writer who will never be uncovered but who exists, at some level, writing the instructions for the representation that we witness.

Desire never quite involves the transit solely from one point to another, from a subject to an object, from one body onto a different one. It is, as in this opening scene, a kind of decentered field of energy, one that delimits an illusion only to break it and disperse it along a broader territory. In reconstituting the elements of this moment of dispersal, the scene is a paradigmatic construction—an allegory, a moment that stands as the emblem of a broader set of circumstances. This is reinforced by the newspaper that lies on the bed next to the young man. The headline reads, “El paradigma del mejillón” (“The Paradigm of the Mussel”), and this, we will discover later on, is also the title of the film of which this scene is a final fragment. The headline’s date (which can barely be read) is Tuesday, October 13, 1985. And on the table itself there is also a LIFE magazine, a commemorative issue for the centenary of the Statue of Liberty. We see this after both voices have moaned and orgasmed at the same time (synchronicity is here achieved), and the voice tells the boy that he did well; a bunch of bills are thrown on the table beside the bed. The young man counts the money—he has been paid well for a job well done. In this brief instant, as he handles the cash, we glimpse a different kind of gaze from him: he’s now become more of a hustler who’s earned his pay by pretending to be an object of pure and innocent beauty.

Freeze and end.

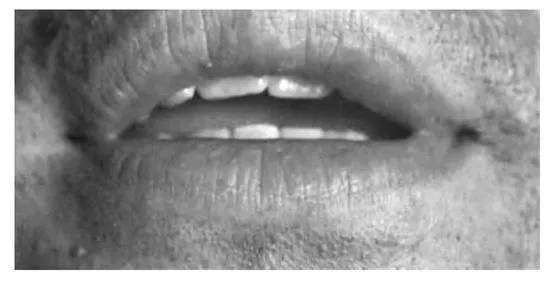

Cut to a shot of the film itself as it winds up in the canister, and a voice that we will later on realize is the director’s (Pablo’s) voice saying, “Freeze and end.” The shot of the editing moment is the second example of Almodóvar’s insistence on the materiality of art (the first one was the rumpled pages of the title sequence), but it will not be the last in this film. Different music is now heard (violins) in a more dramatic register. Curtains are drawn, we hear applause, and as the sweeping violins seem to hit their climax, we see a wonderful shot of red-haired Tina (Carmen Maura), wearing a red top, coming out of the theater—one of the most beautiful shots of Maura in this film, looking left and right for her brother. And as the on-screen audience leaves the theater, we see the title of the film—Law of Desire—written in pink on top of a scene that frames, coincidentally, the three characters that will be the triangulated axis of the film, frozen in a still shot that is then toned down to a sepia-hued black and white. Pablo (Eusebio Poncela), Tina, and Antonio (Antonio Banderas) cross without meeting in the theater’s vestibule. Tina goes off to meet Pablo, and Antonio departs for somewhere else. These initial scenes of the movie are full of color, with Tina’s wonderful red dress and Antonio dressed in complementary black Lacoste shirt and red pants. As he goes into the bathroom to masturbate while reliving the last scenes of the film we have just watched, we are given a disorienting shot of what seems to be a red toilet with a light below, and then a shot of Antonio unzipping his red pants before the camera moves on to his face as he repeats the words the ephebe did not want, at first, to say: “Fuck me.” As Antonio repeats the words, the camera closes in on his face and then does an extreme close-up of his mouth, lips, teeth, and tongue as he repeats fóllame again and again.

FIGURE 3. One of the most beautiful shots of Maura in this film, looking left and right for her brother. DVD still.

FIGURE 4. Pablo, Tina, and Antonio cross without meeting in the theater’s vestibule. DVD still.

The titles on top of the still shot also serve to remind us of the fact that the initial sequence with the pages avoided giving us the title of the film itself—hence the feeling of incompleteness (and also of delay) in those first credits. This freeze shot has always been one of my favorite moments in the film. The fact that what we have seen ends up being just an introduction affords a kind of sexy pleasure of its own: a fast and almost immediate release, a kind of adolescent anticipatory masturbation before the main act. What heightens the emotion for me in this particular scene is the musical effect, but also, I’ve realized after all these years, the fact that this title sequence plays out in the space of the theater vestibule, a place of sexual tension. This will be repeated later, when Antonio searches in the theater vestibule for a ticket to one of Pablo’s plays. There is erotic tension in these vestibules, in these spaces of waiting, that speaks of the movie house itself (or of the theater) as part of a construction. For many years (at least until the advent of the DVD and later, widespread use of the Internet), movie houses were places of desire for gay men, who cruised and had sex in them, either with other gay men or with straight men seeking release. This was true in Madrid after Franco’s death, and to this day in a number of Latin American cities. There has always been erotic tension in movie palaces and theaters, and I am convinced that Almodóvar references this at various moments in Law of Desire. The vestibule here is the meeting point for all characters—they are stars that move in different directions, each obeying its own specific gravitational law.

FIGURE 5. As Antonio repeats the words, the camera closes in on his face, and then does an extreme close-up of his mouth, lips, teeth, and tongue as he repeats “fóllame” again and again. DVD still.

This scene in the vestibule, which properly opens the action of the film we will now watch, follows in many ways the play with illusion and reality that we saw in the initial sequence. Not only a teary-eyed Tina but also the background music heighten the effect of the sublime in a film whose title, The Paradigm of the Mussel, does not point to any sublime feeling at all. Tina’s emotional response to the film bears no relation to a work in which, at least in the end, money is exchanged for sexual pleasure. In other words, the film we have seen does not seem to provoke this emotional response but rather uncovers the mask of the “sublime” in order to reveal an everyday banal reality (e.g., the young ephebe’s voice i...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Acknowledgements

- SYNOPSIS

- CREDITS

- Introduction

- ONE: THE SUMMER BEGINS

- TWO: ART, MURDER, AND LOSS

- THREE: AMNESIA AND DESIRE

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

- About the editors

- Copyright Page