- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

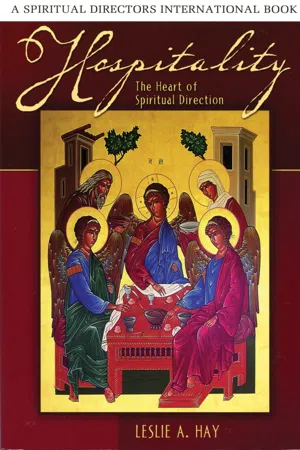

In this latest addition to the Spiritual Directors International Series, professional spiritual directors and those in formation programs learn to extend traditional forms of hospitality by living out its deeper meaning as they explore ways in which the spirit of hospitality enriches the spiritual direction experience. The Spiritual Directors International Series - This book is part of a special series produced by Morehouse Publishing in cooperation with Spiritual Directors International (SDI), a global network of some 6, 000 spiritual directors and members.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hospitality by Leslie A. Hay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Hospitality and the Rule

of St. Benedict

A New Paradigm for Hospitality

Over thirty years ago I discovered a new way of understanding hospitality in an introduction to the Rule of St. Benedict. This new paradigm took me beyond the traditional forms of hospitality that focus on gracious entertaining and providing assistance, to a time-honored, scripturally based tradition that fundamentally means welcoming the mystical presence of God in each person and circumstance I encounter. As you might expect, this enlarged perspective of hospitality initiated a prolonged personal journey of exploration and discovery, prompted by a chance conversation I had while working in a hospital operated by a community of Benedictine nuns. One day I asked the director of nursing service, Sr. Giovanni Bieniek, OSB, herself a member of the community, “How can you do all the difficult things you do for and to the patients?” She replied, “I see everyone as Christ.”1 Although I was introduced to Christianity at a young age, this concept, rooted in Scripture and firmly integrated in the Rule of St. Benedict, was a revelation to me. Over the years, this idea of hospitality—of seeing and receiving all as Christ—seemed to lie dormant in me, but it was merely gestating. As personal reflections often teach us, little did I know then the fruit it would bear, or how it would one day impact my future practice of spiritual direction.

Many years passed before I once again encountered St. Benedict and what he called his “little rule…for beginners” (RB 73:8).2 My rediscovery came by way of a formal introduction to the Rule of St. Benedict, and its underpinning principle of hospitality, in 1983, when my husband and I attended a Benedictine Experience in Canterbury, England, led by Esther de Waal, an Anglican laywoman; Robert Hale, a Camaldolese monk; and John Mitman, an Episcopal priest. Through this experience, and by reading de Waal's book Seeking God: The Way of St. Benedict, I discovered a way of life based on a rhythm of work, study, and prayer. The following year, as a result of this life-changing sojourn, my husband and I began assisting with annual Benedictine Experiences in New Harmony, Indiana, modeled on our own experience in Canterbury.3 These week-long attempts at living a modern adaptation of the Rule of St. Benedict afforded regular opportunities to delve into the depths of St. Benedict's timeless Rule and, subsequently, to deepen my perception and practice of hospitality. Later, as I began to minister as a spiritual director, connections between St. Benedict's instruction to “welcome all as Christ,” and my ministry emerged.

The Rule of St. Benedict

To demonstrate the significance of this Benedictine paradigm for hospitality and its applications for spiritual direction, we need a working knowledge of the Rule of St. Benedict and an appreciation of the person who wrote it. At first glance, looking back to the Rule's sixth-century origins might seem superfluous, but as the lengthy Introduction to RB 1980—the most authoritative translation of the Rule to date—attests, it's actually central to our understanding. We learn that St. Benedict lived in a complex, chaotic time that some have likened to our own era, and when St. Benedict wrote his rule, he was following a long monastic tradition. Rules were patterned after the way first-century Christians lived their lives to provide a context within which people could pursue a call to holiness. Interestingly, St. Benedict would have known and understood that the monastery, with its ascetical practices, was merely the place for the first phase of monastic experience. When a monk had achieved the goal of ascetical practices, which can be defined as “charity or purity of heart, the state in which his own inner turmoil is quieted so that he can listen to the Spirit within him, [he] is ready for the solitary life…[where] there is no rule but that of the Spirit.”4 In addition to ascetical practices, the monastery provided a safe refuge from a society in disarray. So rules gave a civilizing alternative to the tumult caused by the crumbling culture in which people found themselves. As we look at St. Benedict's Rule more carefully, we discover how he was influenced by these considerations.

The introduction is also packed with factual information about Benedict, based on a biography written less than fifty years after his death by St. Gregory the Great. Although history is usually presented through the lens of objectivity, it is also written subjectively, and such was the case with Pope Gregory (540?–604), who had many reasons for portraying St. Benedict in the best possible light. St. Benedict was surely a holy person, but we need to be aware that “while Gregory follows the principal stages of Benedict's career, he is primarily interested in the gift of prophecy and the power of working miracles.”5 He includes many examples of both in his biography to highlight St. Benedict's “progress towards holiness.”6 Gregory's biography was an example of what is known as “hagiography,” which tends to idealize the life of a saint or holy person to inspire others to follow a similar path.

Although it lacks objectivity, we can still learn much from Gregory's account as given in Book Two of his Dialogues, which show that St. Benedict was born to parents of means in the mountains of Nursia, about seventy miles northeast of Rome, in approximately 480 CE and sent to school in Rome, where he experienced a religious conversion. Finding himself at odds with society, he renounced the world as he knew it, and went off to live the life of an ascetic, first with a group at what is now known as Affile, east of Rome, then in solitude for three years at Subiaco. In time, disciples gathered around him, and St. Benedict established a series of twelve small monasteries in Subiaco, comprised of twelve monks each. He then left Subiaco and established a single, larger monastery at the top of Monte Cassino, some fifty miles south of Rome, where he lived for the remainder of his life,7 dying at Monte Cassino around the middle of the sixth century.8

A Hospitable Environment

This brief introduction provides the context from which St. Benedict wrote his Rule, and like most writers, he projects into his Rule aspects of himself and his times, which official biographers sometimes miss. So it's from the Rule itself that we discover concepts that apply to the ministry of spiritual direction. None is more important than the emphasis St. Benedict places on establishing an environment conducive to the ongoing transformation of the monks, himself, and guests. Here are some of the spiritual direction concepts that Benedict implies in his little rule.

Monastic Quest

Anthony C. Meisel and M. L. del Mastro write in their introduction to The Rule of St. Benedict, “Monasticism is the quest for union with God through prayer, penance and separation from the world pursued by men sharing a common life.”9 To facilitate this quest for God, St. Benedict wrote a Rule, a small book of guiding principles, to establish, regulate, and maintain a life-giving community of men, and later women, committed to seeking and serving Christ in every encounter of daily living. St. Benedict was keenly aware of human nature and composed a rule that created an environment where a monk's search for God could be nourished, particularly through prayer, in community and in solitude. St. Benedict's primary objective was to create a stable place where his monks could grow in love, “his central vision of the quest.”10 From these authors we recognize that St. Benedict clearly understood that he needed to devise a “guide”—as regula, the root of “rule,” is more accurately translated11—that not only ordered the communal life of the monastery but also provided holistic support by which this desired growth in love and union with God could occur. He “tries to provide a framework where spiritual life is not only possible, but natural and normal.”12

It's easy to see, as St. Benedict did in his monastic community, that providing a hospitable environment for spiritual direction entails offering a safe, open place where directees can explore their “quest for union with God” in the context of their prayer, stemming from the ordinary events of their daily lives. It's also natural to understand that above all else, our aim is to facilitate the “central vision of the quest” that is this “ever-expanding, enriching exercise of love.”13

Let us now turn to the Rule itself to trace its development and discover its key components. Benedictine monk and scholar Terrence Kardong writes, “The Rule of Benedict (RB) is generally acknowledged as the most influential monastic rule in the Western Church.”14 This emphatic statement makes clear the role that monastic scholars attribute to the Rule and the influence it has had in shaping monastic life over many centuries. We learn, too, that the Rule was likely written in Monte Cassino between the years of 530 and 550 CE. While some portions of the Rule can be traced to an earlier document, Regula Magistri (Rule of the Master, RM), originality is not as important here as what St. Benedict does with this earlier document. Kardong says that RM is a longer, detailed, legalistic document that is suspicious of human nature. In contrast, the Rule of St. Benedict is a shorter version about the size of the Gospel of Matthew, and contains seventy-three chapters.15 By comparing the two rules, we discover that St. Benedict isn't so much interested in the minutiae of daily living, although some detailed instructions are given, as he is in assuring that the monks have what they need as they journey toward holiness. St. Benedict trusted Christ and the human potential for change.

A Balanced Daily Rhythm

Learning about the Rule also teaches us about St. Benedict's way of living, which includes a daily rhythm of work, study, and prayer that provide a hospitable framework for a balanced life. In his work the monk supplies the physical needs of the monastery and builds community. Through study he expands his knowledge of Scripture and the wisdom literature of the Holy Fathers, and through prayer he nourishes his relationship with God, self, and others. Additionally, the Rule is structured around six important spiritual values: obedience, stability, conversatio morum (fidelity to monastic life of transformation), humility, silence, and hospitality. These values are the anchors for Benedictine spirituality and describe a holistic process by which we live: a life focused on conforming to the will of God through a variety of channels; a stability of heart centered on God and in the service of the common good; an attitude of hopeful expectation for ongoing transformation; a humility or meekness of being, which impels us to stand before God as we really are; and a reverence for the “wordless Mystery”16 we call God. As this brief overview of the Rule reveals, it provides a balanced rhythm for daily living and shared values for living in community to supply the monk with a hospitable environment to grow in love. And it's the Benedictine charism of hospitality—welcoming all as Christ—that makes possible the living out of these core values.

A Hospitable Approach

St. Benedict knew Scripture well and integrated it into the very fabric of his life and, subsequently, into the Rule. Repeatedly, he demonstrates that the real source to be imitated is the life of Christ, and as abbot, he understood that he needed to model Christ's teaching not only in his words but also in his actions, “not only Christ-to-be-obeyed, but Christ the shepherd (RB 27), Christ the healer (RB 28) and Christ the brother (RB 64 and 72).”17 With Christ as his model, St. Benedict states his mission near the end of the Prologue: “Therefore we intend to establish a school for the Lord's service. In drawing up its regulations, we hope to set down nothing harsh, nothing burdensome. The good of all concerned, however, may prompt us to a little strictness in order to amend faults and to safeguard love” (RB: Prol. 45–47).

Safe Place for Ongoing Transformation

St. Benedict desired most of all to create a safe place where his monks could come together to live in community respectful of individuals as each journeys toward union with God devoid of anything harsh or burdensome. It's unlikely that St. Benedict would have been thinking specifically in terms of extending what in contemporary language might be called “emotional” hospitality, but I think he addressed this on a very deep level, intuitively realizing that by approaching spiritual transformation holistically and hospitably, free of fear or concern, the monk would be better able to discover his faults and amend them in the context of a loving community. And he knew that he and his monks were all enrolled in the “school for the Lord's service,” and that his role as abbot offered a means for his own ongoing conversion.

Just as St. Benedict provided his monks a safe place for ongoing transformation, so must we do likewise for spiritual direction. While I have no specific goals when meeting with directees other than offering my total presence to them in a safe and welcoming environment, it's clearly my desire, like the physicians who tend our bodies, to “do no harm.” Additionally, I want our time together be a place where directees can explore even the most painful and difficult things in their lives without having to bear anything “harsh” or “burdensome” from me. On occasion, I'm sure I've failed in this area of hospitality, and I'm grateful for the members of my peer supervision group who help me process whatever is going on in me that may have led to this lapse. By being attentive to my own prayer and behavior when meeting with a directee, I, like the abbot, have the opportunity to grow continually “in the Lord's service.” Additionally, we, like St. Benedict, have the occasion to provide a safe place for the directee's ongoing transformation.

Cultivating Compassion, Patience, and Perseverance

Another way the Rule approaches hospitality is through Benedict's desire to “safeguard love,” which I interpret as cultivating compassion. Throughout the Rule are many instances of how the monks are to be fairly and lovingly treated as individuals with different needs. Consider, for example, this passage: “It is written: Distribution was made to each one as he had need (Acts 4:35)” (RB 34.1). This chapter title aligns the philosophy of distribution of community goods with Scripture. In the monastery, all property was held in common, and St. Benedict understood, unlike many of us today, that “fair” and “equitable” don't necessarily mean “equal” or “same,” and he made provision for individual difference with regard to both body and spirit. While many of us know stories of horrid monastic abuses, St. Benedict's rule dictates humane treatment. For example, he writes: “An hour before mealtime, the kitchen workers of the week should each receive a drink and some bread over and above the regular portion, so that at mealtime, they may serve their brothers without grumbling or hardship” (RB 35.12). St. Benedict wanted to prevent what he often referred to as “grumbling” in the monastery. By instituting a “rule” that actually met the needs of the monks who were to serve the meal, he obviated bad feeling. This example demonstrates that Benedict understood, like Maslow centuries later, that when our basic survival needs are met, we can attend to the deeper desires of our hearts, such as recognizing ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Hospitality and the Rule of St. Benedict

- 2. Hospitality: Its Multifaceted Dimensions

- 3. Hospitality as Modeled by Christ

- 4. Challenges to Practicing Hospitality

- 5. Becoming Hospitality

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography