![]()

Chapter One

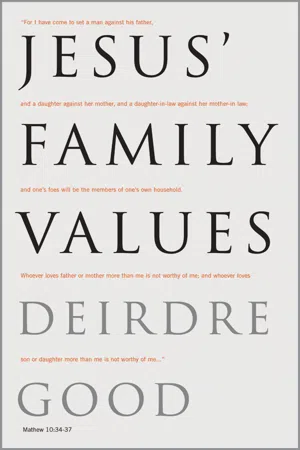

THE BIBLE AND FAMILY VALUES

When I was about thirteen, I wrote an essay for homework on the importance of wood in modern life. Having identified only two items, namely telegraph poles and wooden shafts in mines to support tunnel construction, I asked my mother’s opinion. “What’s the most important thing wood is used for today?” I asked her. “A bed,” she said. I was sufficiently taken aback to remember the story to this day. However, her answer points not just to the need for rest (at that time my father, an ordained priest, was working in a teacher training college, and she had her own job as a physiotherapist, in addition to household responsibilities that included two teenagers), but to the importance of structures of support for her life and that of her family. She herself, of course, was the primary “structure of support” for her husband and children, and while she considered a bed to be the most important use of wood, no mere thing would be the most important support structure in her life.

To this day my parents’ primary support structures include each other, daily prayer time together, the routine of daily work despite “retirement,” meals, recreation, and affection shared, as well as work and recreation taken apart from each other. The needs and difficulties and interests attendant upon a large network of extended family and parish relationships provide a different kind of support for my parents, who have both a vocation and passion for ministry Their baptismal vows, marriage vows, and his ordination vows are crucial structures of support for them and have remained constant through radically different settings — rural East Africa where two children were born and raised; urban England with two adolescents growing up; tropical Fiji, far distant from any relatives; urban England again, but this time with responsibility for an aging parent.

This core family of two adults and two children looks very much like the archetypal conservative Christian family promoted by groups like James Dobson’s Focus on the Family. The sources of support for this family — the God of Jesus Christ, Holy Scripture, purpose-driven lives — seem very similar, if not identical, to the sources of support for mine. But move one degree out of my core family into the extended family, and every possible variation that can be found in modern Western society exists — except perhaps polygamy, although I couldn’t absolutely guarantee that! There are divorces, remarriages, step-relatives, partnerships (heterosexual and homosexual) without benefit of marriage, ex-spouses and ex-spouses’ children. There are people in my extended family for whom there are no English terms to describe the nature and degree of relationship.

Further, there are lots of people in my extended family, related to me by no more than one degree of separation, for whom the sources of support my parents’ generation consider indispensable — the God of Jesus Christ, Holy Scripture — are peripheral if not meaningless. And there are still more members who find their sources of support in scriptural Christianity but understand family as far larger than those related by blood or indissoluble marriage. But what characterizes my extended family members as family is an extraordinary degree of permanence within flux and change, brought about by the family’s own response to itself. Every divorce, every relationship without benefit of marriage has caused my parents deep distress and consternation; but every exspouse, new spouse, unmarried partner remains in their thoughts, love, prayers, and, perhaps more tellingly, on the guest list of their fiftieth wedding anniversary.

But would all religious groups understand that my family reflects legitimate “family values”? Yes, according to a 2005 Valuing Families resource on the Web site of the National Council of Churches (USA). The package “is designed to inspire Christian families to honor and prayerfully support families of all shapes and sizes” and connect them with discussions and activities to help them identify and appreciate the many characteristics that shape families today. Focus on the Family, on the other hand, proscribes sex outside of marriage for believers (whether homosexual or heterosexual). While the group understands scripture to condemn homosexuality and premarital heterosexuality, it mandates acceptance of those violating these ordinances, as we can see in the example of Jesus’ compassion for the women taken in adultery. Similarly, FamilyLife.com explains that conservative evangelicals understand God to release people from the lifelong covenant of marriage in only two circumstances: consistent and unrepentant immorality (based on a reading of Matt. 19:7–9) and when an unbelieving spouse deserts a believer (based on a reading of 1 Cor. 7:15–17).

What exactly are family values and where do they come from? If you Google “family values” you might find, “Looking for Family Values? Find exactly what you want today, www.ebay.com.” Values become whatever you want them to be on eBay. But if you tried a similar search on texts that existed in Jesus’ time, you would be in trouble immediately. There is no word in Greek or Hebrew that exactly corresponds to the modern word “family”; the closest Greek word, oikia, or oikos, means variously household or house, like bet in Hebrew, which similarly means house and can be used for household in the sense of family lineage. Two other Hebrew words used for related groups of people are toldot and mishpachah, generations and clan or tribe. Similarly with the word “values” — any Greek or Hebrew word that might be translated “value” refers specifically to monetary or market worth. Of course, our word “family” comes from the Latin word familia, but for the Romans, the meaning and the reality were far more similar to the Greek oikia and the Hebrew bet than to our modern “family,” as we shall see.

So if we can’t find “family values” anywhere in the Bible, or in the linguistic world of Jesus, when and where does the phrase begin to appear? What constitutes family values and who decides? What can we find in the teachings of Jesus or other Christian scripture that speaks to family values today? What would “family” have looked like in the world and time of Jesus? Is there any scriptural warrant for elevating “family values” to a primary position in Christian belief systems today? What would a scripture-defined “family” look like today, and what would its “values” be? These are the questions that we will explore.

Where Do Family Values Come From?

Most Americans assume the exclusively domestic function and private character of our houses, and we identify the home as a place of refuge from daily work. The pinnacle of the American Dream is home ownership, and the preferred home is the one-family house. But these are modern ideas going back only to the Victorian period. When we consider the home as a place for the raising of children, we must remember that childhood as we know it, an extended time of sheltered nurturing, was practically invented by the Victorians, and reserved to wealthy families. Suburbia as a bedroom community for the city originated in the Victorian period with the advent of rapid public transit. When people use the term “traditional family,” what is meant may look a lot more like a Victorian family than a family in the time of Jesus.

For example, Victorian religious art ordinarily depicts the Holy Family as a calm, detached, affluent nuclear family, typified by James Collinson’s The Holy Family. Here a young, healthily padded woman sits on an invisible seat in front of the corner of a red brick building set in a garden with hollyhocks. Her carefully draped dress and cloak are immaculate, as is her person. Under a simple nimbus, a pure white veil with no visible means of anchoring partially covers her hair. The child stands in perfect composure on her knee, reaching out to a dove resting on Joseph’s hand. Joseph, also with nimbus, wears a long clean garment under a cloak whose careful folds mark a citizen of leisure; his hair and beard have been professionally groomed. Each character wears an expression of serene gravity. Behind the tableau a cypress frames a calm meandering river under a blue sky with a few tentative clouds.

A significant departure from this pattern is John Everett Millais’ Christ in the House of His Parents, also known as The Carpenter’s Shop. The controversy surrounding this work suggests the extent to which Victorians considered the Holy Family to be elevated above and apart from the experience of ordinary working-class family life. Millais clearly understood that Joseph’s carpentry shop was located in the house, a confusion of contexts abhorrent to the emerging Victorian ideal that particular places be reserved for particular functions, and that the home be protected from the incursions of work. For a twenty-first-century viewer, however, the painting is a perfectly respectable representation of an extended family at work in some ancient period. In the center a mother kneels comforting a child perhaps ten years old, clad in a white shift, who has hurt his hand. All of the figures in the painting lean toward the wounded boy in concern; the younger apprentice, perhaps John the Baptist since his breeches are made of some wild animal’s fur, carries a bowl of water for cleansing the wound. The shop is clean, littered only with the expected wood shavings; lumber is stacked and tools hung tidily in the background; a dove hunching on a ladder behind the table watches the child with a worried look. The door of the shop reveals a pastoral landscape with green fields under a blue sky beyond; from a pen of clean farm animals close to the house, even the rams and sheep focus upon the child with concern. The Victorian outcry against the painting may demonstrate the extent to which working-class life was considered incompatible with the upbringing of children and the maintenance of a proper home. So deeply was the understanding of respectable family divorced from the reality of working-class life that Millais is recorded as having hoped that Queen Victoria’s private viewing of the painting had not been too “corrupting.”

The term “family values” was popularized in the Republican presidential campaign of 1992 after Dan Quayle attributed the then recent Rodney King riots in Los Angeles to a “breakdown of family structure, personal responsibility and social order,” and then cited as “mocking fatherhood” the TV sitcom Murphy Brown, in which Brown chooses to bear and raise a child by herself, rather than to abort. While a number of the components of the current “family values” debate have been in public and political contention for decades, the current debate about “family values” as a package dates to 1992.

In 1980 a White House “Conference on Families” took place, and in 1983 the Family Research Council associated with James Dobson was incorporated. The Family Research Council (FRC) extols the virtue and value of the two-parent, marriage-based family as the foundation of society. According to its Web site, the FRC holds that marriage can only be the life-long union of one man and one woman, and believes that sexual relations should occur only within lawful marriage.

In scholarly circles, it was also in the 1980s that several publications appeared on family, house, and house church in the period of Christian origins. By the mid-eighties a consensus existed: households were at the center of the mission of the early Christian movement. The house church was vital for local churches or assemblies, serving as a focal point for prayer, Eucharist, and instruction. It was a base for outreach, and as a community it was a place to experience and exercise fellowship or love of brothers (and sisters). Early believers of the Christ cult existed in a wider social world. Architectural evidence from Dura-Europos indicates that Jews, followers of the Roman cult of Mithras, and Christians all adapted private homes for worship purposes. As far as the New Testament is concerned, evidence from Luke and Matthew indicates that from 50 to 150 CE early believers met in the private homes of wealthy members of the group. Since the gatherings included a common meal, they probably took place in a dining room or living quarters. Nothing distinguishes the buildings that hosted such assemblies from domestic houses. Subsequently, larger houses were probably altered and used in part or perhaps primarily for worship. At the same time, believers probably continued to meet in houses. In the mid-second century, a gradual expansion to larger buildings and halls is evident.

Once the centrality of the oikos as the basic social, legal, and economic unit within Hellenistic and Roman society and the importance of the oikos as a place of individual and public identity was understood, studies on networks of the oikos and the family took on a new importance. Moreover the wider political North American context in which scholarship has occurred since the 1980s (and probably before) gives such academic undertakings a particular relevance.

A major distinction between traditional and progressive scholarship concerns the application of biblical material: traditional scholarship views the Bible prescriptively while progressive scholarship views biblical material primarily descriptively and secondarily considers its current application. Traditional scholarship regards biblical teaching on marriage and family as a blueprint for the modern home. There is no gap between the text and my life. Progressive scholarship prefers to “mind the gap” and to describe as fully as possible historical contexts in which meaning is disclosed as the first step toward understanding biblical statements on marriage and family. For example, material from Hebrew scriptures has an entirely different social, economic, and historical context from material in the New Testament. Observing this historical context respects the historical circumstances in which divine disclosure took place. Paying attention to historical contexts goes some way toward preventing an interpreter from projecting his or her own mental landscape onto the text.

Recent traditional writing (e.g., Andreas Köestenberger, God, Marriage, and Family) understands marriage and the family to be the primary divinely instituted order for the human race. These institutions are to be characterized by monogamy, fidelity, hetero-sexuality, fertility, complementarity, and permanence. (Note the prescriptive language: these institutions are to be characterized…). The New Testament, Köestenberger continues, defines marital roles in terms of respect and love as well as submission and authority. While there is “neither male nor female” as far as salvation in Christ is concerned (Gal. 3:28), there remains a pattern in which the wife is to emulate the church’s submission to Christ and the husband is to imitate Christ’s love for the church (Eph. 5:21–33). The married couple witnesses to surrounding culture and ought to understand itself within the larger framework of God’s end-time purposes in Christ. Again, note the prescriptive language: “the wife is to emulate” “the husband is to imitate” “the married couple.. .ought to understand.” How do we know marriage and family is the primary divinely instituted order of the human race? By what means is marriage and the family selected over any other divinely instituted human institution? Such a judgment indicates that there are some covert presuppositions operating to privilege marriage and family over anything else. As for “neither male nor female” in Galatians 3:28, the text is misquoted. The original text actually reads, “there is no male and female,” alluding specifically to the text of Genesis 1:27, the creation of humanity as “male and female”; what baptism into Christ does is to transcend the original complementarity, not to perpetuate the polarity. In other words, in Pauline thought, baptism creates an identity exclusive of gender, whether that means by unifying the male and female, or by creating an entirely gender-free category. Galatians dispenses with gender categories, Ephesians emphasizes them; by subordinating Galatians to Ephesians, Köestenberger overrides Paul’s mandate for gender-free baptismal life in Christ, and reinscribes sexual differences as operative. This is an example of how certain texts are privileged in support of a modern traditional understanding of marriage; most scholars would agree that Ephesians was not written by Paul, and therefore should not be elevated over Galatians, which everyone agrees was written by Paul.

Surely marriage today is not the same thing as marriage in Eden or in ancient Israel, or in the time of Jesus. It is too obvious to say that there is no one single understanding of marriage in the Bible and that collapsing teaching on marriage and family into one single model reduces diversity to the point of distortion. Moreover, Jesus wasn’t married, and Paul seems to commend singleness or sexual asceticism over marriage. What do Jesus’ singleness and Paul’s commendations imply for the human condition? If barrenness is generally viewed as divine disfavor, is Jesus the exception that proves the rule? What does this say about Paul?

There is no one understanding of social roles of parents, either in the Old or New Testaments. Why should a passage from 1 Timothy 2:15 or Titus 2:4–5 be selected to prescribe women’s God-given calling as wives and homemakers? What about New Testament descriptions of women’s prophetic roles as wives and mothers, as is the case with Jesus’ mother? Finally, in Köstenberger’s whole book, there seems to be no discussion of slavery, whether in ancient Israel or in the Hellenistic or Roman worlds. This omission is a problem. Slavery was normative in the world of Jesus’ time. Even poor households employed slaves. Not to know something about the role of slaves in a household or family setting is to have a partial, not to say distorted, view of New Testament texts.

Carolyn Osiek and Margaret MacDonald’s A Woman’s Place: House Churches in Earliest Christianity points out that modern literary and rhetorical analysis of ancient male-authored texts has increased our awareness that ancient descriptions of men and women promote authorial agendas rather than describe real people. Nevertheless, these scholars claim to discover a more expanded role than the dutiful wife in Ephesians, and to identify women as patrons, teachers, and dinner hosts with influence in households and house church communities. Women could be married, divorced, widowed, or martyred. A Woman’s Place interprets archaeological material from catacombs as showing women taking leadership roles in family funerary banquets. Ancient sources assuming domestic slavery, the authors suggest, indicate that the topic of whether to hire a wet nurse or nurse the baby oneself was of great interest. If one hires a wet nurse, what kind of nurse has the best influence on the life of the young child? Understanding such questions to reflect concerns of mothers (or fathers) at the time of Christian origins “minds the gap” by indicating distance between ancient and modern concerns.

Traditional family values proponents claim that biblical authority as they construe it overrides all other authorities and warrants imposition on all Americans. Second, they hold that the only scripturally warranted family consists of a male and a female in monogamous lifelong marriage and their children, and only such constellations should be accorded the legal protections and privileges enjoyed by families. Third, they usually locate scriptural authority in the specific words of an English translation (such as the King James Version) read out of context and with minimal reference to the historical context or the linguistic world of the source. Such a reading of scripture, by definition, assumes permanence of meaning and a fixed context which admits of little interpretation. By this means order and unity are imposed upon scripture, and when that is not possible, certain texts — such as thos...