- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

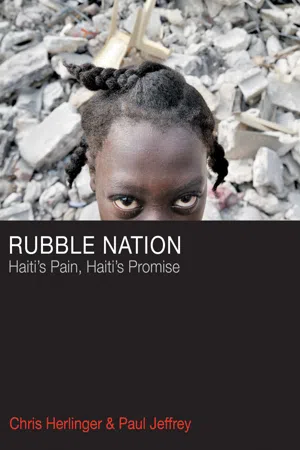

Rubble Nation tells the story of post-quake Haiti through interviews with Haitian citizens and aid managers. Each interview adds a layer to our understanding of the suffering of the people and of the heroic efforts to ameliorate that suffering. The narrative is set in the context of the country's history and the Haitian government's effort to repair and rebuild their nation. The photographs capture images not only of individuals struggling to survive, but also of the innate dignity and generosity that arises in the midst of the struggle.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rubble Nation by Chris Herlinger,Paul Jeffrey in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781596272293Topic

Theologie & ReligionCHAPTER

1

Rubble Nation

Port-au-Prince is a city of jagged edges—of potholes and glass, of exposed wires and pipes, of open sewers and rotting mango peelings, of sludge, dirt, and mud. The edges are most visible in midday when the sun is at its height and the contrasts of glaring sun and dark skin, of light walls and shadowed alleyways, are most striking. So it comes as a relief when the softening afternoon light begins to slide slowly into twilight, as it did at 4:53 p.m. on January 12, 2010.

On that day, high up in Port-au-Prince’s hilly Delmas neighborhood, Anouk Noël and her younger sister, Rode, were in their house, starting to think about dinner. Anouk had not been well in the week since her twenty-ninth birthday on January 5, but she was feeling better—well enough, anyway, to think about going out the next day and have her photograph taken by a professional as a belated birthday gift. Such outings are special to Anouk; she suffers from dwarfism and needs family members to carry her because she cannot walk.

Anouk and Rode knew right away that the vibrations they felt were ominous. Port-au-Prince had experienced tremors before, but these became horrifying—the sisters’ house was swaying and the two heard loud, low rumbles, sounding like bullets and breaking glass. Later, others described the racket as goudougoudou—a vernacular Kreyòl term describing the sound of the quake that came to mean the earthquake itself. Frightened by the sharp vibrations, Rode fled, along with the sisters’ mother, Melanie, and brother, Jimmy, just as the six-story building next door collapsed onto her family’s house. Though momentarily relieved to be outside, a dazed Rode panicked when she remembered that her sister was still in the damaged house. She ran back, saw her sister, who had passed out, and carried her through the debris and onto the street. There the two met their mother and brother; Jimmy had injured his foot, but not seriously. The family stood amid glass and dust, dirt and fallen concrete; rubble from the collapsed house next door buried members of several families. A year later, a visiting construction engineer wondered if bodies were still concealed under the dusty wreckage of gray concrete and white plaster. “This is crazy,” he said. “We might be walking over people right now.”

Up the hill from Delmas, Astrid Nissen, a German humanitarian worker, was at her desk working on a budget proposal for her agency, Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe, when the roaring began. She heard her Haitian colleagues shouting “earthquake, earthquake.” They fell to the floor, praying. The swaying was surreal, she recalled, but the building withstood it. Once Nissen collected herself, still shaking and trembling, she called a colleague in Colombia and told her that Port-au-Prince had just been struck by an earthquake. It was the last international phone call Nissen would make for a while. After collecting her shoes, her cigarettes (“I needed them”), and reuniting with her partner, Jean Gardy Marius, a Haitian physician, Nissen spent the next eight hours fielding calls on Skype, giving interviews, but not sure precisely what to say. At first she thought, hope against hope, that “it couldn’t be that bad.” But over the hours, the news worsened: perhaps the most ominous signal of the quake’s magnitude was the fact that the National Palace had collapsed. Early on, Nissen went downtown, where some of the worst damage had occurred, and kept muttering, as if in a daze, “It isn’t true. It isn’t true.” But it was true—corpses littered the street, bodies were scattered on the sidewalk. Things only got worse in the following days: Marius’s sister was among the victims, and bodies continued to line the road—eventually the sight of corpses being lifted onto the backs of trucks for burial became commonplace. For weeks afterward, packs of barking dogs roamed the streets at night, looking for flesh.

On that first night, it was dark by 5:30, and the streets were packed with people walking uphill because they feared a tsunami. Many were covered with dust, and everywhere, Nissen recalls, “it smelled like burning tires.” Other, more pungent smells would emerge within days. Immediately following the quake, one had to be careful when driving—the roads were packed with “people, people, people,” especially at night, since so many people were sleeping on the streets.

At 4:53 p.m., January 12, 2011, a year to the moment after the quake occurred, Nissen looked up at the gentle, clear blue sky of dusk, and said, “Life goes on.”

It does, and it did. The Noël family, shaken and scared but without serious injuries, had to make some tough decisions, like where to go, what to do with their damaged home, what to do about money. The home had to be abandoned, at least for the moment; the family did not know if it was safe. They stayed at one displacement camp followed by months in another, where conditions varied depending on the weather. “People helped each other out, but it was muddy,” Anouk Noël recalled. Often it didn’t feel safe.

Almost a year to the day after the earthquake, Anouk Noël was back home. As part of a program to help the disabled and their families, she and her family received a cash grant. They used it to purchase cosmetic items they resold as a small business venture to provide some income. Their home had also been partially repaired. Anouk sat in a small unfurnished living area, chairs and tables lost in the quake. In one corner of the room stood a wheelchair, given as part of the family’s assistance, which Anouk uses when she is out of the house—such as when she sings soprano at regular events for the disabled. Her powerful, commanding singing is a gift, and friends call her a “bundle of joy.” But on this day, she was serious and quiet. Living with a physical disability is particularly challenging in a country where mobility is difficult even for the able-bodied. Getting around became even more treacherous in the jagged postearthquake landscape of damaged roads, collapsed buildings, and mounds of rubble.

Rubble. Even a year later, parts of Port-au-Prince lay in rubble. Because on January 12, 2010, in a matter of seconds, Port-au-Prince—the centrifugal force of Haiti, the seat of its government, its economic and social life—had been destroyed, and Haiti had become Rubble Nation.

CHAPTER

2

“There Is Still So Much to Do”

In those first days of January it was like this: downtown Port-au-Prince looked as if the quake had happened only hours earlier. Homes and apartments were crushed. The smell of decaying flesh wafted through the air. The sides of some buildings jutted out, looking as if they would fall into the street at any moment. The arbitrary nature of the quake was striking: an untouched building stood next to one that had completely collapsed. It was unsettling to see a building cut in half, with furniture and desks, filing cabinets, and sinks exposed to the harsh midday sunlight. It was even more startling to see those who refused to move to the tent cities. To this day, the worst-hit area of downtown Port-au-Prince remains vivid in my memory because, in the seemingly postapocalyptic rubble and decay, people were angry. They were tired of answering questions from journalists and aid workers. As the sounds of hammers and nails punctuated the air, some shouted at us to go away.

Six months later, it was disheartening to see how little had changed. It was true that parts of Port-au-Prince looked marginally better, as at least some debris had been removed. But generally, the capital city looked beaten down and felt as if it were at a standstill. In some ways a pause was actually needed. Few Haitians I spoke with on July 12, 2010, dwelled on the six-month anniversary of the quake. It was an artificial marker for U.S. journalists and aid workers, who were connected to the outside global media cycle. Haitians were looking only for a break from hardship, misery, and blight. Instead of the anniversary, they focused on the welcome distraction of the World Cup—many people believed that if it were not for the World Cup, the streets of Port-au-Prince would have been filled with protesters, exasperated by the Haitian government’s inaction. “People are waiting for someone to show the way to the right place,” one of the young Haitian humanitarian workers with the Lutheran World Federation said about the need for leadership and inspiration.

People I spoke to freely acknowledged that the continuing work of repairing, rebuilding, and rehabilitating Haiti had been hindered by endless obstacles and enormous challenges. Haitian aid worker Sheyla Marie Durandisse said, “If you look at the numbers of those we have served, it is impressive. But compared to the continued needs, you see challenge after challenge.” Durandisse’s colleague, Jean Denis Hilaire, was even more stark in his assessment. “It’s like a drop of water in the bucket. There is still so much to do.”

At the center of the disappointment and frustration were the hundreds of thousands of people in need of permanent housing who remained stuck in the tent cities. The refrain of “building back better,” often repeated after the quake, was heard less and less now that there was actually very little building going on at all. That problem was the result of a number of tangled webs: questions of who owns and who rents land; disputes about whether property owners should be compensated for rubble removal; debates about whether the government could (or should) declare eminent domain and move people out of the crowded camps in Port-au-Prince’s public squares, parks, and golf courses. “The biggest challenge that we are facing now is ensuring that everyone has a safe and sustainable place to live,” said Prospery Raymond of the UK-based humanitarian agency Christian Aid. “There is not enough land currently available to build permanent houses for everyone who needs them. The Haitian government needs to address that issue as a matter of urgency.”

Fueling all of these worries was the perception by many that the Haitian government had not moved quickly enough to resolve these problems. Others argued that neither a weakened government nor well-intentioned nongovernmental organizations—commonly called NGOs—advanced the efforts to assist earthquake survivors. Raymond insisted, “International and local NGOs must improve their level of coordination and collaboration with the state. Now that six months have passed, there is no longer any excuse for not working effectively together.”

Long-standing social ills now fully exposed

The fortitude and resilience of Haitians was evident at the St. Thérèse camp in Port-au-Prince. Yvan Chevalier, a member of the camp’s management committee, described conditions in his camp of more than 4,300 persons as “stable,” but that was the best that could be said. As I watched a group of children kick around a soccer ball for an impromptu game, Chevalier emphasized that any sense of stability would likely be short-lived. “More people are expected here,” he said, shaking his head, because another nearby camp was closing down. Life within the camps remained cramped, tense, and uneasy. Residents were still dealing with overwhelmingly crowded conditions, crime, and rape. Downpours, a normal part of Haiti’s rainy season, were worsening conditions in the camps. On the day I visited Chevalier’s camp, mud was everywhere, despite the brave attempt of residents to build a system of moats and boardwalks to keep water and mud out of the tents. Tent areas were also fortified with stones and concrete to protect against the rains.

Trauma remained an issue—how could it not? “January 12 left us with so many problems,” said the Rev. Kerwin Delicat, an Episcopal priest and the principal of the Sainte Croix School in Léogâne, the quake’s epicenter. “People are still traumatized,” he said. “I see it in the daily life of the people. They are very nervous.”

Trauma had done more than simply exacerbate problems that existed in Haiti before the earthquake—misfortunes ranging from poverty to hunger, from overcrowding in Port-au-Prince to poor infrastructure. These long-standing social ills were now fully exposed, as if stripped bare in the devastation of the earthquake. Aaron Tate, one of my Church World Service colleagues, told me that he and others were frustrated by the slow recovery, noting that there “were a lot of dreams early on that this was an opportunity to build a ‘new Haiti’ better than the old Haiti.” But, he said, “the reality is that with such devastation, it is an incredible effort to rebuild at all.” Tate said he and others remained firm in their commitment to place the control of rebuilding in the hands of Haitians. But outsiders continually overlooked the reality that the humanitarian workers themselves were still recovering from loss—of loved ones, homes, and jobs. “They are working hard and going far beyond what we could reasonably expect of them to provide emergency relief and recovery, but they do so against great odds,” Tate said. While the largest and most critical issues, especially housing in Port-au-Prince, “have been too big for anyone to address,” he added, “on a smaller scale, you do see successes.”

This was true. While the frustrations and challenges posed in Haiti were most easily witnessed in Port-au-Prince, there was progress around the edges, both in the capital and in other cities affected by the quake. In Jacmel, where house repair was underway, the sense of improvement and energy were palpable. Sainnac St. Fleur, a construction foreman working for Diakonie Katastrofenhilfe, said residents were united in purpose and working hard to see the one-time French colonial city rebuilt. “What we’re doing is very important,” St. Fleur said. “We have many, many people in need.”

It is probably too easy to make facile comparisons between the megalopolis of Port-au-Prince and the smaller, more intimate Jacmel, a less complicated place to work and navigate. Still, judging Haiti solely through the lens of Port-au-Prince might invite pessimism and hopelessness, but I don’t think it does. I met too many good, talented, committed, and politically savvy Haitians to believe the naysayers. But it is also obvious that something needed to be done about the scale of congested and crowded Port-au-Prince—the capital is not only too large a spoke in the wheel for all of Haiti, in many respects it’s nearly the whole wheel. As St. Fleur, the construction foreman in Jacmel, put it, the capital is not only too big, “it is too politicized a city.”

Sylvia Raulo, who was about to leave the Lutheran World Federation to head the Haiti program of Norwegian Church Aid, spoke of the accomplishments of the first six months since the quake this way: given the enormous weight of Haitian history that had produced the problems of malnutrition and hunger, poverty, lack of adequate water and housing, the achievements of the initial six months were perhaps the minimum that could be attained. She pointed to “the things we haven’t heard about. There were no political riots, there was no major food crisis, there was no major outbreak of disease.” (This was before the cholera outbreak of late 2010.) “It’s an achievement that we’ve managed to get the horror scenarios out of the picture,” she said. “So far, so good.” So far. A very cautionary “so far.”

But was that good enough? I heard speculation earlier in the year about the need to build new cities outside of Port-au-Prince—visions of a Haitian version of Brasilia, the capital of Brazil which was built in less than four years (1956–1960) in a centralized and “neutral” location, away from Brazil’s largest cities. But such talk had abated; unfulfilled visions have a long history in Haiti. The Comedians, Graham Greene’s satiric novel about Haiti in the mid-1960s, includes a rather somber assessment of the country: “Haiti was a great country for projects. Projects always mean money to the projectors so long as they are not begun.”

Should humanitarian agencies criticize governments?

The lack of housing was not the only problem. Relief supplies were held up in customs—not for reasons of malfeasance, but simply because of inefficiencies. Raulo said that humanitarian groups and other nongovernmental organizations had legitimate grievances with the Haitian government in this respect. She told me about a case that demonstrated the obstacles Haitian authorities faced. After Raulo spent a day clearing up a shipment question, she found out that the country’s entire customs operation was being run out of an average-size office, no larger than her own, where a dozen harried, overworked employees manage customs for all of Haiti. “There is a real issue of capacity,” Raulo said about the losses experienced by the Haitian government—losses that include not only huge numbers of buildings but also equipment and, of course, personnel. “They lost a lot of material and human capital.”

Other relief workers were not as diplomatic. Some were publicly impatient—even angry. An op-ed that appeared in the June 25, 2010, Los Angeles Times pushed the question of whether or not humanitarian agencies should criticize governments. The author was Erik Johnson, humanitarian response coordinator for the Danish organization DanChurchAid, which works with Christian Aid, Church World Service, and others in an international network of agencies called ACT Alliance. In his piece, Johnson took the Haitian government to task, saying authorities “had lapsed into the classic pattern of corruption, inefficiency, and delay that holds the country hostage.” Johnson, a veteran of a number of large-scale emergencies, said that in more than a decade of humanitarian work, he had “never seen camps like those in Port-au-Prince. International standards defining what people are entitled to after a disaster are in no way being met. The Haitian camps are congested beyond imagination, with ramshackle tents standing edge to edge in every square foot of available space.” He argued that “massive, aggressive intervention is required” and said the Haitian government had clamped down on the importation of goods, making it difficult for humanitarian assistance to get to beneficiaries. “Though it’s important that ...

Table of contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Message

- Content

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Postscript

- Afterword

- Interview with Chris Herlinger and Paul Jeffrey

- Questions and Topics for Discussion

- Select Bibliography