![]()

MOSES, PHARAOH, THE PROPHETS AND US

BEFORE OR AFTER THE SESSION

Many participants like to come to the group conversation after considering individually some of the issues that will be raised. Others like to take time following the session to do further processing. The following five reflective activities and questions are intended to open your minds, memories and emotions regarding some aspects of this session’s topic. Use the space provided here to note your reflections.

What do you already know about the story of Moses, the Israelites in Egypt, Pharaoh, Sinai, the Ten Commandments and the Golden Calf? (If you want to recall the stories, then turn to the book of Exodus: chapters 1-7, 13-14, 16-17, 19-20, 32.)

Think of Pharaoh today as “the rat race,” the tendency to get pulled back into a consumer culture in spite of your best intentions, and the desire to always want more. Think of God as the One who still invites us into an alternative covenant relationship based on fidelity to God. Where is your allegiance most of the time?

How’s your prayer life? Does it ever include energized, even contentious engagement with God, or is it pretty innocuous and polite? What does the way you pray tell you about your knowledge of God and God’s ways?

What practices do you follow (like Sabbath) that enable you to maintain at the center of your life the things that matter most to you and to God?

Where do you experience worship that does not narcoticize you, but inspires and stirs you to deal with life and death issues in a way that matters to you and to God?

ESSENTIAL: BRUEGGEMANN, MOSES AND THE PROPHETS

Play the first part of the DVD (about 16.5 minutes), in which Walter Brueggemann lays the groundwork for the discussion which is to follow.

When you encounter a new teacher for the first time you may actually pay as much or more attention to the teacher as to the content of what the teacher is saying, especially when the teacher is one who is as dynamic and forceful at Walter Brueggemann. Share your initial impressions of Brueggemann with one another. What impact did he have on you both in his presence and in his words?

The members of the small group meeting with Walter had an opportunity to ask questions of him. If you were there, what questions would you have wanted to ask him based on his opening presentation?

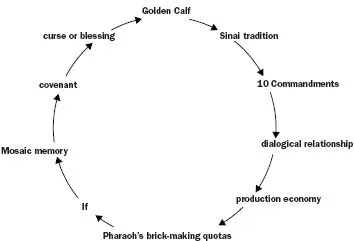

Here we are in a series that focuses on the prophets of Israel, but we are beginning with events in the great narrative of Israel that took place at least 500 years earlier. Before we go on, let’s take a moment to be clear about the connections between the story of Moses and the place of the prophets in the story of Israel. As a group, speak about the words and phrases in the circle below, using them as linking ideas between the age of Moses and the era of the prophets. (Note: If you have a large group, you might want to do this activity in pairs or groups of three, especially if people are quite new to one another and possibly intimidated by speaking in a large group.)

Now play the rest of Session 1. The group discussion surfaces the issues that will be covered in the rest of your session. You’ll have the opportunity to choose options based on group interest and time available.

OPTION 1: NEGOTIATING WITH GOD

Prince asks this question of Walter:

You make the suggestion that Moses was in fact negotiating with God. I’m wondering how people today will take and process that comment? Are we really in a position to negotiate with God?

Walter responds:

That is the peculiar genius of the Jewish faith. Most of our theology comes out of Greek philosophy. When you operate in the categories of Greek philosophy there’s no chance to bargain, negotiate or rap with God. It is so Jewish to be engaged in that disputatious kind of way. In Exodus 32, at the end of the Golden Calf thing, Moses really persuades God to change God’s mind. This is the ground of serious prayer. Most of our prayer life is so innocuous and polite because we don’t think that we have a mandate to be that seriously engaged with God.

Damon adds:

And we can be [engaged with God]. Remember the woman who kept knocking: “I’m not leaving!” and she kept knocking. And so we have to be more persistent and God will change his mind. Yea. That’s good.

Later Prince adds this reflection:

Negotiation is a way of continually providing people with options as they struggle with the dilemmas of life. If anything is finalized, then that’s the end. That’s it. But through the process of negotiating with God, you can continually re-invent and re-invigorate and eventually reach a point where you are whole or moving in that direction.

What do you think of this more Jewish notion of negotiating with God? Have there been times when you have engaged with God in this way? Did you feel like you were negotiating with God and that there was a real possibility that God’s mind would change?

Could you imagine changing your prayer life to do more “bargaining, negotiating or rapping with God”? How would you make that into a prayer practice?

OPTION 2: GOD LEARNING TO BE GOD

Walter talks about God in this way:

The God of the Bible really doesn’t fit our old formulations of omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent. Omnis don’t work because this is a God who is much more engaged and at risk with us in the process. That requires a different portrait of God and a different sense of ourselves as human beings and as persons of faith.

Ariel reflects:

God is learning to be God by duking it out with us.

Try testing out this notion of two visions of God by engaging with one another in a debate about the nature of God. Half the group will insist that God is “omni”: all-powerful, allseeing and all-present. God is in charge and will not be moved. The other half will speak up for a God who is malleable, willing to engage with humanity, to be changed in the process, discovering who God is by “duking it out” with us.

If you want to talk less and embody more, then use your bodies, both individually and collectively, to express the difference in these two visions of God. You could create tableaux (group compositions) with your bodies arranged to represent the difference. You could also use movement to express the two different relationships between God and us.

Whichever of these methods you use, be sure to take time to debrief afterward and identify what you learned in the process.

OPTION 3: COMMODIFICATION OR FIDELITY; YOU CHOOSE!

What does Pharaoh look like in our society? Walter responds in this way:

In our society, Pharaoh takes the form of the rat race, and the rat race drives us to want more, to have more and to do more. We will never make enough bricks to satisfy ourselves! It is the great seduction of a consumer economy to think that you always have to have more.

And later in the conversation he goes on to say:

I think the summons is, in every way we can, to resist commodification. That’s going to be different for each of us in our circumstances. I suspect one thing it means is to turn off the television. It probably means to go to the neighborhood park [to] watch sports rather than [watching] big spectator sports that are all commodification. I think it requires great intentionality to be present as a deciding, responsible agent, rather than a pawn of the ideologies that push us around.

Joanna responds:

It sounds like we have commodification and then we have relationship almost as though they are opposed to each other. It reminds me of a book I read in which one person says to another, “Don’t ‘thing’ me—don’t treat me like a thing.” When we commodify other people then we are cutting off the relationship. It sounds like between us and God, it is the relationship that matters.

Walter:

That’s exactly right. The defining ingredient of real human life is fidelity. It’s not wealth, power, control, knowledge. It’s fidelity. And you can see that breaking up when universities no longer have students; they have consumers. Doctors no longer have patients; they have consumers. It’s relabelling us all according to a consumer ideology. It’s the death of community.

Describe a place in your life where creeping consumer ideology has undermined relationship and fidelity? In what ways is this a concern for you? To what extent are you willing to keep paying the price?

The practice of sabbath is presented by Walter as one way for individuals, families and communities to develop resistance to a consumer-oriented society:

Sabbath-keeping is the regular decision to opt out of the production-consumption rat race. I think we do not have energy for neighborly relationships of fidelity unless we have something like Sabbath at the center of our lives because we are exhausted by producing and consuming. One of the things busy people like us tend to do is just to add more things on but not stop doing things that are actually contrary to the truth of our lives.

During the conversation Walter defines Sabbath in this way:

A regular scheduled disciplined time in which we do not practice the values of the world which are the values of production ...