![]()

PART 1

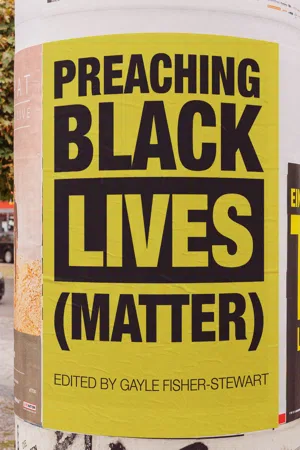

Preaching Black

Lives Matter

![]()

1

Introduction

IS THERE A WORD FROM THE LORD?

Gayle Fisher-Stewart

We really “had church today!” is a familiar expression among African Americans following a Spirit-filled worship experience. The implication of this folksy phrase is that the Spirit of God had moved with such power that all social barriers were removed and worshipers were able to “have a good time in the Lord.” The passionate, celebrative style of preaching had no doubt reached the depth of worshipers’ souls and had “set them on fire!” The Word of God in sermon and song had spoken to the conditions of the gathered community, who could say emphatically that they had “heard a word from the Lord.”

—Melva Wilson Costen1

If the only thing a preacher hears from a congregation week after week is how much they enjoyed the sermon, it is very likely that the preacher is not dealing with challenging content.

—Marvin McMickle2

“African American spirituality is a spirituality that was born and shaped in the heat of oppression and suffering.” It included a tradition of Jesus that connected the dissonant strands of grief and hope in the experience of black people who trusted in God to make a way out of no way. “Blackness is the metaphor for suffering,” [Prof. J. Alfred Smith] said. “To know blackness is to be connected to the suffering, hope, and purpose of black people.”

—Reggie L. Williams3

Bryan Stevenson, the genius behind the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, has said that racism can be eradicated when we become proximate or close to one another. Sometimes I wonder if that, in fact, is true. How much closer can you get to a person than to engage in the sexual act that creates new life? How much closer can you get to a person than to give your child over to the Black wet nurse and have that woman’s milk coursing through your child, nourishing your child, providing the antibodies that will keep your child healthy? How much closer can you get to someone who works in your home every single day? Who is on duty twenty-four hours a day? Who cooks every meal you eat, who shares your living space, who shares the air you breathe? How much closer do you have to be to be proximate?

The German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer tested proximity. When he came to New York in 1931 on fellowship at Union Theological Seminary and affiliated with the Black Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, under the leadership of Adam Clayton Powell Sr., he found a Black Jesus who suffered with Black Americans in a White supremacist society. For Bonhoeffer, the ministers of White churches of New York lacked content in their sermons. They preached everything except of the gospel of Jesus Christ—a gospel of resistance, of survival. He found in the worship of Abyssinian a style that had a different view of society than White churches. It was a style that acknowledged the suffering of Black people in a racist society that viewed African Americans as subhuman and legitimized brutality against them in so many ways.4 Preaching came alive and strengthened those in Abyssinian’s pews to fight against a Church and society that viewed Blacks as less than human.

In Harlem, and at Abyssinian, Bonhoeffer found the Black Jesus who understood the colonized lives of African Americans as opposed to a White Christ who was used to justify Black suffering and maltreatment. He found and worshiped a Black Jesus who disrupted White supremacy; a Black Jesus who negated the White Christ who, since colonial times, had been at the foundation of racial terrorism, served as an opiate to sedate Black people to see themselves through the eyes of Whiteness as subhuman, and to accept their unjust lot in life as a condition that had been ordained by God. The White Christ inculcated racial self-loathing for Blacks. They were taught to hate everything African: African religion, African customs, African traditions. They were taught that they descended from heathens and had no history worth the time of Whites to study. Bonhoeffer found a Jesus who was the antithesis of the Christ Whites claimed to follow, but whose actions and lives told otherwise. He found a Black Jesus who turned White supremacy on its head, who dispelled the notion of a White-centered world where “morality and racial identity are comingled and measured in proportion to the physical likeness to white bodies.”5 He came to understand that White Christianity was infected with and by White supremacy and a Black Jesus was a frightening disruption to Whites who were made comfortable when Black people accepted the structures of a White world.6

A Black Jesus, on the other hand, enabled oppressed African Americans to imagine him outside White societal structures and a Christianity that upheld White supremacy. A Black Jesus had a “this world” focus that pursued justice here and now, as opposed to an other-worldly orientation that encouraged Black people to accept their dehumanized lot on earth and look toward freedom in heaven. This focus in the here and now mandated activism in the politics of a racist society that denied Black people their share of what was God’s. Under the tutelage of Adam Clayton Powell Sr., Bonhoeffer learned that the Black church was the center of the community and the people were involved in “applied Christianity,” an active faith that changed the society in which African Americans found themselves. Powell knew that the Black church needed to reach beyond itself and to that end, he developed a worship environment that would help anyone, regardless of race, to understand the other and to engage in an active love with Jesus at the center.7 Bonhoeffer studied W. E. B. Du Bois, who argued:

The historical Jesus would be unwelcomed in a Christian society that is at home with white supremacy. In their general religious devotion, white-supremacist Christians are participants in Jesus’ crucifixion because, in truth, their Christianity was not about Christ; white racists wedded Jesus to white supremacy, shaping Christian discipleship to govern a racial hierarchy.8

While Bonhoeffer’s experience was in the 1930s, we find ourselves in a similar position today with White supremacy rearing its ugly head and the Church largely remaining silent. Bonhoeffer’s learnings are relevant today and we must look to those who have left templates for us as we preach a word that upsets a Christianity that looks little like the Black Jesus Bonhoeffer found in Harlem who animated Black churches to be the Church, the body of Christ, in a world where suffering seemed to have the upper hand.

Preaching the gospel steeped in a Black Jesus of Nazareth takes courage and there are examples to guide us. Preaching requires vulnerability—especially prophetic preaching: preaching that troubles the waters of a country, a world that seems determined to live in the sin of racism. Brené Brown defines vulnerability as risk + uncertainty + emotional exposure.9 Jesus risked it all to confront the unjust powers of his day. If the body of Christ is to be his representative on earth, the Church must risk it all for the gospel, a gospel that challenges this country’s original sin and the role the Church played in it. The preacher must be willing to risk upsetting the congregation, at the least, to move it from its place of comfort to a place where eliminating racism becomes its call. There will be uncertainty because it is unknown how the people will initially react and later act as a result of the sermon. Finally, the preacher must risk something of themselves to let the congregation know what is in and on their heart. The Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray said there is a certain fear when a minister attempts to preach the Word of God. That fear results from the realization that we are so small and God is so great and, regardless of the level of education, the number of years preaching, or the hours of sermon preparation, our preaching will always fall short because human beings fall short and God’s judgment always looms near.10 There is no perfect sermon.

The Rev. Florence Spearing Randolph put it all on the line and opened herself to being vulnerable when she mounted the pulpit on Sunday, February 14, 1941, at Wallace Chapel AME Zion Church in Summit, New Jersey. She was about to trouble the waters with a sermon that was so controversial for its time that it was reported in both the White and Black press. A female African American, she preached a sermon titled, “If I Were White.” In a sermon that would be relevant today, but was written for her particular time, Rev. Randolph lifted a mirror to the hypocrisy of America and White people in the treatment of African Americans. She preached of the need for racial justice and economic parity that could have provided the foundation for Martin Luther King Jr.’s challenge against America’s three evils—racism, capitalism, and militarism—and the need for White people to take responsibility for the mess they created.

She preached during a time of war. World War II was raging, which added additional vulnerability to her words as they could be seen as challenging, not only Christianity, but also this country’s patriotism. She took a proverbial knee in the pulpit, much like Colin Kaepernick’s protest against the singing of the national anthem. I can imagine this Daughter of Thunder skillfully opening a wound in the psyche of White Americans by declaring that if Whites “believed in Democracy as taught by Jesus [and] loved [their] country and believed . . . [the United States], because of her high type of civilization, her superior resources, her wealth and culture,” then that country should be a bastion of peace and make sure all her people are cared for because “charity begins at home.”11

From her pulpit in this supposed White church, she declared that White America needed to pull the “beam out of thine own eye” (Matt. 7:5, KJV) before finding fault with other nations. A precursor to Bryan Stevenson’s call for being proximate, she called for Black and White ministers to exchange pulpits. She urged the various organizations in White churches to study Black history and realize that Black Americans had demonstrated their loyalty by dying for this country from 1776 on. But then she hit the jugular vein and said, “If I were white and believed in God, in His Son Jesus Christ and the Holy Bible,” as if being White precluded believing in all three or even one, that she would challenge all who took the pulpit to speak against all that degrades God’s people: racism, prejudice, hatred, oppression, and injustice. She put the responsibility for racism squarely where it belonged, telling the White race that it should show its superiority by taking responsibility for ending racial prejudice. She used scripture to make her point: if one says they love God but not a sibling in Christ, that person was a liar (1 John 4:20). She mounted her challenge to Whites to end discrimination against Blacks in housing, education, entertainment venues, and health care. She recognized and indicted systemic racism. She confronted Whites who were ignorant of Black history and called for them to put books on Black history in the libraries and to see that Black history was taught in schools. Then, with just a hint of the task that is before her, she admitted that she did not know how successful she would be if she were White, but that her conscience would be clear. She ended with a dream in which she, as a White person, was trying to avoid a Black person who was gaining on her. Finally, the Black person stood side by side with her and her wrath was kindled. The Black person was equal to her, but then she turned to act on her wrath and was “struck dumb with fear, for lo, the Black man was not there, but Christ stood in his place. And Oh! the pain, the pain, the pain, that looked from that dear face.”12 Would Whites act differently if Jesus were physically Black?

Randolph’s sermon was daring for the time and daring for a woman because women still had a difficult time finding acceptance from men both inside and outside the Church that they had a call from God to preach. Randolph was fortunate because the African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AMEZ) Church began ordaining women in 1894. A lot was at stake for her, as a woman and as an African American to preach as she did. Race prejudice and violence were an ever-present threat. Jim Crow, segregation, and the lynchings of Blacks who did not “know their place” were never far from the minds of African Americans. It was not outside the realm of possibility that she could have been lynched. She knew she was vulnerable; she took the risk any...