- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Using the latest available data, Dr. Stewart provides a critical, historical study of the exploitation of a major agricultural resource by a developing country. It traces the political economy of Papua New Guinea's coffee industry from its pre-independence origins.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Coffee by Randal G. Stewart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1The Origin of the Coffee Industry in Colonial Papua New Guinea

DOI: 10.4324/9780429037771-2

Australian Colonialism in Papua New Guinea

Australian colonialism in Papua New Guinea was administered initially under a League of Nations mandate and, after World War II, under a United Nations Trust Territory arrangement. These international arrangements had an important impact on Australian-Papua New Guinea colonial relations. But this impact was not direct. It was felt less in what was done by the coloniser and more in what was not done. Australia did not commit atrocities in Papua New Guinea. However, nor did it display much interest in developing the territories. Exploitation did occur but this was within the boundaries of indentured labour and administrative regulation. Thus, Australia's impact was felt in the way it imposed an administered structure of taxation requirements, labour contracts, encouraged free contributory labour on roads and other civic projects, and through the colonisers' mild pressure to consume and produce for the market. This was exploitation of a kind, and racist, but it was exploitation of a type that could allow the whites, then and now, to think they were simply doing a job in an underdeveloped territory.

The Australian colonial regime was above all, administrative in structure and purpose. It focused more directly on social considerations - - education, health, law, etc. - - rather than on economic development. When industrial and economic development was considered at all by the colonisers, it was usually as infrastructure, rather than in terms of the need to construct a self-sustaining economy. Indeed, there was resistance to economic development among the administrators especially if this meant fostering aggressive, indigenous entrepreneurs. The Australian Department of External Territories, which administered Papua New Guinea from Canberra after World War II until Independence in 1975 was not run like the British Colonial Office. It did not develop a core of Oxbridge-trained administrators who were hostile to capitalism. Rather, the colonisers' resistance to capitalism, expressed in the policy of gradual development - - which proposed that all indigenous people should develop at the same pace - - was a pragmatic response to the circumstances. It made a 'virtue' out of a necessity, because a financially strapped Administration, in a colony of virtually no interest to most people in Australia, with Paul Hasluck, a Minister of undoubted ability but who was relatively lightweight in the Menzies cabinets, had little choice. Hasluck was reduced to begging each year for increases in the territories' meagre budget.

Such entrepreneurial drive as was allowed to exist was provided by a small number of white settlers. They were to be backed by infrastructural provision from the Department. At least, this is the relationship the Department of External Territories would have liked to have had. The parameters of this relationship were, however, contested. Colonial politics revolved around the pull of resources from a penny-pinching Administration and the push of the whiles to have it go beyond the provision of minimal infrastructure. The outcome, in the economic history of Papua New Guinea, was a colonial experience that caused even greater regional fragmentation and diversity than already existed geographically and culturally. Benign neglect occurred in regions not attractive to white settlers. Stunted development occurred in those regions where white settlers could 'make a quid'.

The Administration, adopting the economic way of thinking of the period, usually favoured development in Papua New Guinea which was complementary to Australia's stage of industrial development. This meant that Papua New Guinea's exports should match Australia's exports. Invariably, this dogma placed the colony in the role of supplier of raw material for Australian transformation and consumption. This economic way of thinking was influential in Britain in the period after the war and found a receptive audience in the Menzies government. It was, of course, a misguided approach. It represented less a fear of colonial competition and rather more a conceptual belief in linear development - - that countries pass through stages of growth - and a commitment to the crudest analysis of comparative advantage. It was racist but benign when applied to economies. However, when applied to people it was racist and malevolent, especially when, as so often happened, it turned into its opposite and became a policy for suppression of development and discouragement of individual improvement.

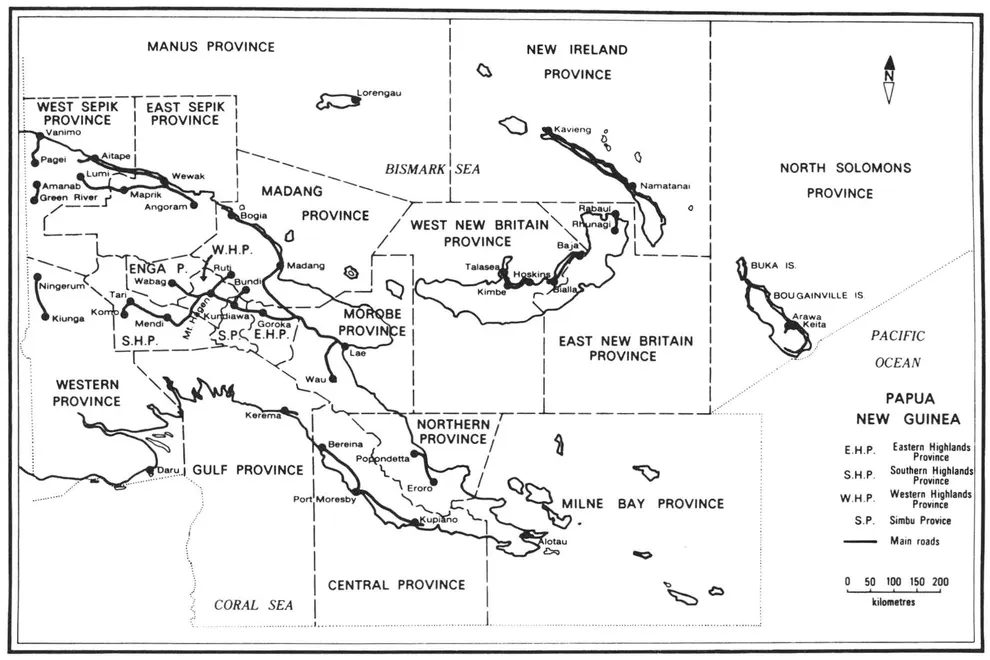

Arabica coffee is an industry in which white settlers found they could both 'make a quid' and get Australian assistance to develop a raw material required by Australian industry and coffee drinkers. Arabica coffee is grown in the Papua New Guinea Highlands (see map). The term 'Highlands' refers to the complex of mountain ranges, intermediate valleys and plateaus of the central

cordillera, among which are the Hindenburg, Kubor, Schrader, Bismarck and Kratke ranges of mountains, the Wahgi, Chimbu, Goroka and Bululo valleys and the Kainantu plateau. The physical characteristics of the Highlands region make it highly suitable for coffee production. As described by Howlett, "the terrain is characterised by steep, often sheer slopes, sharp ridges, the scenes of innumerable landslides and swift rivers in the steep narrow valleys". (Howlett 1967:33-34) The high altitudes and the accompanying temperature and rainfall patterns make the Highlands climate "on the whole regarded as favourable for coffee production". (Barrie 1956:4)

The Goroka valley and the Kainantu plateau, which together make up the Eastern Highlands Province, contain the optimal physical and climatic conditions for growing coffee. The Goroka valley is really a series of valleys which occur between mountain ranges, such as Mount Otto and the Asaro ranges. It is drained by two rivers, the Asaro and the Bena Bena. The Goroka valley is known for its mild temperatures - - much lower than those on coastal lowlands - - relatively low humidity and cool nights. Goroka town was the first Highlands town to be established (1939) and it became an important transport and market centre both because of its strategic location at the heart of the highlands and because of its attraction for white settlers. Goroka also became and remains the centre of the Highlands coffee industry. The Coffee Industry Board (previously the Coffee Marketing Board) is located in Goroka as is the country's largest coffee exporter, ANGCO. Goroka was the area in which pioneers of the coffee industry, Jim Leahy and Ian Downs, settled and established the first coffee plantations. For these reasons, the empirical work for this study is based on the Goroka valley.1

The development of the commercial coffee industry in Papua New Guinea Highlands was from the beginning marked by the same distinctive historical circumstances as foreign penetration of the Highlands itself. In particular, the key role played by white individuals and the administrative state, the backwardness of existing social relations and the lateness of penetration were characteristic of both penetration and the development of the coffee industry.

The 'gold that grows on trees': white planter success in the early days of the coffee industry

Small areas of Arabica coffee were first planted in the Highlands at Kainantu and Korn farm (Mount Hagen) as early as 1935. Little more was planted before 1939 except at Wau. Many of these early plantings were by missions, hence in very small quantities. During World War II, it appears that the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit (ANGAU) may also have experimented with small areas of coffee production. In addition, robusta coffee has been grown in coastal areas of Papua New Guinea since the turn of the century. Coffee exports from New Guinea in the years preceding the war were slowly increasing but still totalled only 74 tons in 1940-41.

The first person to grow coffee commercially in the Highlands was Jim Leahy. He and his brothers, Mick and Dan, were the first white men to explore the Eastern Highlands, in 1933. Jim later took up residence at Goroka where a village west of the township offered him 150 acres, and the Administration, although it had misgivings about encouraging white settlement in the Highlands, granted him residency and finally an agricultural lease. This was in 1947, the year he planted his first six acres of coffee. Dan and Jim Leahy were not rich men. Dan recalls that the money he spent on the failed Kuta coffee plantation - - £40,000 to £50,000 - - almost broke him. Jim stated that the main reason he went in for coffee and not tea was because it could be grown economically in practically any amount and because coffee processing machinery was relatively simple and inexpensive. (Finney 1973:44)

The period 1948-51 was the trial period for white settlement in the Highlands as far as the Administration was concerned. It was not then encouraging alienation of land from indigenous ownership and only about half a dozen plantations were established in this period. But in 1952, the Administration abruptly changed its tune and in May of that year it publicly opened the Highlands to applications for land alienations. (Finney 1973:44-45) In the following July, Jim Leahy harvested coffee from his original six acres. It was "a year of world shortage, and the price he was paid, seven and ninepence a pound, has never been equalled in Papua New Guinea since. Then everyone started to plant it." (Ashton 1978:191) The land rush was on. Ian Downs, then Acting Director of the Department of District Services and Native Affairs, was sent to Goroka to investigate. This land rush, with which Downs was later to become personally involved, resulted in the alienation of dozens of agricultural properties in Goroka, totalling 3,550 acres between 1952 and 1954, a tenfold increase over the acreage alienated during the previous three years.

The amount of land leased to Europeans in the years 1952-54 was also high. "Prior to 1952, 4,833 acres was leased to Europeans in the central highlands but with the lifting of the last restrictions on settlement in 1952 in the next two years nearly three times this amount, 13,109 acres, was leased" (Donaldson and Good n.d.:146), although this was still a small area compared with the total area of the Goroka valley. (Finney 1973:45) It was, however, enough to ensure that by 1955 the plantation section of the industry was basically established in the form in which it exists today and that plantations would dominate the coffee industry in the early years of colonialism.

In 1955 there were 55 European holdings in the Eastern Highlands, out of 76 in the Highlands as a whole. Today there are 44 large plantations in the Eastern Highlands and 88 in the Highlands overall. In 1955, plantation holdings in the Eastern Highlands covered 14,642 acres of land although only 2,026 acres were under cash crop cultivation. Today 12,800 hectares of land are covered by large plantations, of which some 10,800 hectares are under cash crop cultivation (mainly coffee). In 1955, 45 non-indigenous and more than 2,000 indigenous workers were employed on these plantations. By 1954, although the plantations had only been established in the previous four years, the Highlands had established itself as the second largest coffee-bearing area in New Guinea.

Today Highlands coffee totally dominates the coffee industry and the plantation sector remains proportionally an efficient and important part of that industry. While the bulk of coffee is produced by smallholders, and they own by far the bulk of coffee trees, the high productivity of plantations makes their contribution to production an important one.

The settlers lost little time expanding their influence beyond production into both marketing and the political sphere. Jim Leahy bought out a number of other plantations in partnership with his Collins and Leahy nephews. In 1960 he led a syndicate of three in buying Asaro plantation from Jim Taylor, a move west which culminated in Collins-Leahy setting up and managing the first coffee processing factory in Chimbu at Kundiawa. In the east, Collins-Leahy spread as far as the purchase of Mick Leahy's Markham Valley property, and established trade stores and marketing channels in Kainantu. (Ashton 1978:192) Jim Leahy was primarily interested in the commercial and agricultural development of the coffee industry, though he was responsible with Jim Taylor and George Greathead in founding in 1953 the first political association in the industry, the Highlands Farmers and Settlers Association (HFSA). In 1956, Ian Downs resigned as District Commissioner and

with a feeling of relief ... I entered the private sector as a beginner to join in the expansion of the coffee industry and face the marketing problems that would have to be overcome before coffee could make so much more possible for the Highland people. (Downs 1978:246-247)

Downs became the key political figure in the development of the coffee industry in the 1960s, as founding Chairman of the Coffee Marketing Board to February 1965 and then as President of the HFSA from 1956 to 1968.

Much of the work of Downs and the HFSA was intensely political. The need for political action and organisation began virtually with the first substantial quantity of coffee production in Papua New Guinea. The problem was that of finding a market for a crop that had increased from 87 tons in 1953-54 to over 2,000 tons in 1960. When a panic about markets began in 1959-60 the estimated 1961 crop was 3,000 tons, with a carry-over from 1960 of nearly 300 tons. (Cartledge 1978:54) The HFSA began a campaign in January 1959 to ensure that the coffee industry in Papua New Guinea would not be inhibited due to its inability to find a marketing outlet for the crop. Related to this campaign was the Administration's change of policy to discontinue active promotion of coffee planting by smallholders, though assistance was still given freely when sought and plantings continued at a high rate.

The main activity of the Administration and the HFSA in this period was to establish a most-favoured nation agreement with Australia for Papua New Guinea coffee. The 1959-60 season was the first year that many trees would come into bearing and it was also the first that a lot of coffee from Papua New Guinea had to be marketed(Cartledge 1978:52) The HFSA argued for a 1 shilling per pound duty on coffee coming into Australia from places other than Papua New Guinea. This would, according to the HFSA, allow Papua New Guinea to take its rightful place in the Australian market. The Australian Treasury and Department of Trade were against any attempts to apply new duties, and argued that any such measure was contrary to the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) and also to GATT. (Cartledge 1978:67) However, they did offer Papua New Guinea a remission of the existing duty of threepence per pound for new coffee. The offer was made at a somewhat acrimonious meeting in March 1961 and was grudgingly accepted by Papua New Guinea in August 1961 as a temporary measure pending Tariff Board enquiry. The Papua New Guinea growers were of the opinion that the threepence remission did not provide sufficient incentive to clear the market and in any case did not offer an incentive for Australian manufacturers to take increasing amounts of Papua New Guinea coffee as production continued to expand. The HFSA began an intensive lobbying campaign during the period between August 1961 and the Tariff Board enquiry of April 1962, and achieved great success. Not only did the HFSA manage to have existing duty on coffee raised, but Papua New Guinea coffee was given very high levels of remission on other coffee if large quantities of Papua New Guinea coffee were taken. (Cartledge 1978:64-65)

Coffee production in Papua New Guinea was also given special treatment when Australia entered the 1962 and 1968 ICAs on behalf of its colony. The 1962 and 1968 ICAs in coffee made specific allowance for the colonial relationship. Article 67 of the 1962 ICA stated that: "Any government may, at the time of signature or deposit of an instrument of acceptance, ratification or accession, or at any time thereafter, by notification of the Secretary-General of the United Nations, declare that the agreement shall extend to any of the territories for whose international relations it is responsible, and the Agreement shall extend to the territories named therein from the date of such notification."

The wording of Article 67 does not make clear in what manner the dependent territory's exports are tied to the metropolitan country's imports. Is it the case, for example, that the dependent territory's de facto export quota under the agreement is the amount of coffee it can sell to its metropolitan power (i.e. the contracting party to the agreement)? Is the dependent territory forbidden under Article 67 to export to other countries? Or, conversely, is it the case that a dependent territory's export quota is the same amount of coffee as the import quota of the contracting party to the agreement? In other words, can Papua New Guinea under Article 67 export 156,000 bags, regardless of what portion goes to Australia? Finally, what happens under the agreement when the exports of the dependent territories begin to exceed the imports of the contracting party to the agreement? Is this extra coffee non-market coffee? Is it time for the colony to be given its own export quota, or can the contracting party to the agreement with its dependent territory become, in effect, an exporting group and be given a joint export quota? If so, does the importing country receive votes in the International Coffee Organisation (ICO), according to its importing status or its exporting status by virtue of its tied relationship with an exporting dependent territory? These problems became central to the 1966-67 crisis in Papua New Guinea - - when its production increased beyond the limit allowed to be exported to Australia - - for they gave rise to the phenomenon of netting, the belief on the part of planters that Papua New Guinea could export to member markets an amount equivalent to the import quota given to Australia. We will see in Chapter 5 how the politics of the 1966-67 crisis drew the planters in Papua New Guinea into conflict with the metropolis and the Administration over the extent to which the former as guardian of the international agreement should interpret it in. a way that put a squeeze on plantation capital in Papua New Guinea.

The HFSA supported a policy, embodied both in the International Coffee Agreement and in the most-favoured nation remissions of duty, which would link territory production with Australian imports. The HFSA argued that such a linkage was necessary because the coffee industry in Papua New Guinea was in the early stages of development and because marketing conditions were difficult in the early 1960s. The HFSA argued strongly "that in theory and practice New Guinea may never produce sufficient coffee to meet the total Australian requirements". (Cartledge 1978:29) However, the establishment and reinforcement of a linkage between Territory coffee production and Australian importers - - both through the ICA and through the remission of import duty in Australia - - created a much more complicated political situation in the industry. This was 1960, a time when most of the rest of the world was being decolonised and newly independent nations were eager to see the process of decolonisation completed throughout the world. The process of structuring Papua New Guinea's economy to be complementary to Australia's, firmly accepted by all political actors in Papua New Guinea, was regarded with suspicion in other places. Thus, the linkage between Territory production and Australian imports had to be made on the basi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents Page

- List of Illustrations Page

- Preface Page

- Acknowledgments Page

- Introduction

- 1 The Origin of the Coffee Industry in Colonial Papua New Guinea

- 2 Producing Coffee

- 3 Exchanging Coffee

- 4 Administering the Coffee Industry in Colonial Papua New Guinea

- 5 Crises in the Colonial Coffee Industry

- 6 Transition to Post-Colonial Politics in Papua New Guinea

- 7 Who Owns the Coffee Industry in Independent Papua New Guinea?

- 8 Dividing up the Coffee Industry Among Black Élites

- 9 The Role of Technocrats in the Post-Colonial Coffee Industry

- 10 Case Studies of Elite Exploitation of Smallholders

- 11 The International Coffee Agreement

- 12 The Politics of International Coffee Regulation

- 13 The Use of Liberal, Negotiated, Institutionalised Global Commodity Agreements to Cause the Underdevelopment of Papua New Guinea's Coffee Industry

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index