eBook - ePub

For a Just and Better World

Engendering Anarchism in the Mexican Borderlands, 1900-1938

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

For a Just and Better World

Engendering Anarchism in the Mexican Borderlands, 1900-1938

About this book

Caritina Piña Montalvo personified the vital role played by Mexican women in the anarcho-syndicalist movement. Sonia Hernández tells the story of how Piña and other Mexicanas in the Gulf of Mexico region fought for labor rights both locally and abroad in service to the anarchist ideal of a worldwide community of workers. An international labor broker, Piña never left her native Tamaulipas. Yet she excelled in connecting groups in the United States and Mexico. Her story explains the conditions that led to anarcho-syndicalism's rise as a tool to achieve labor and gender equity. It also reveals how women's ideas and expressions of feminist beliefs informed their experiences as leaders in and members of the labor movement.

A vivid look at a radical activist and her times, For a Just and Better World illuminates the lives and work of Mexican women battling for labor rights and gender equality in the early twentieth century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

University of Illinois PressYear

2021Print ISBN

9780252086106, 9780252044045eBook ISBN

9780252052989CHAPTER ONE

The Circulation of Radical Ideologies, Early Transnational Collaboration, and Crafting a Women’s Agenda

[To members of] la Casa del Obrero Mundial, … [the Casa is a] mother—simple and loving…. [I]t is time to realize that men are unnecessary, it is time to realize that the opinion of one is not always the opinion of the entire collective.

—Reynalda González Parra, 1915

Hailing from Mexico City and among thousands of migrants moving to the port of Tampico in 1915, Reynalda González Parra was one of the early female contributors to the anarchist press at least five years before Caritina Piña arrived. González Parra took to the pen, as thinkers before her did, expressing her frustration with the status quo through the small but influential anarchist press. The opening up of anarchist collectives and their accompanying newspapers to op-eds on women’s status, poems, and thought pieces by women like González Parra, as well as editorials by male colleagues about the need to embrace women as “compañeras en la lucha,” paved the road for the increased participation and visibility of women such as Caritina Piña in postrevolutionary Mexico. What conditions gradually increased the visibility of women’s issues in the anarchist press during this early period? Why did a segment of the female population become attracted to anarchist principles? And how did they seek to put those ideas to practice, especially concerning a specific women’s rights agenda in the context of labor? The gradual opening of prolabor organizations and collectives such as the Partido Liberal Mexicano and the Casa del Obrero Mundial to include women’s issues in their periodicals and encourage women’s participation in their ranks sparked a more robust presence of women in labor matters. The founding of such organizations, however, did not happen in a vacuum.

Anarchism’s Influence in the Mexican Borderlands

Since its founding in 1823, Tampico emerged as a bustling port in the Gulf of Mexico with socioeconomic and political ties to Bagdad and Matamoros in Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Galveston, New Orleans, Havana, San Juan, and other ports across the Atlantic. Ideas about worker autonomy and livable wages found a welcoming environment in Tampico and its vicinity and circulated widely, transforming the port into one of the leading labor radical sites of the world by the early twentieth century. Tampico became the ideological hub and gateway to the Mexican Northeastern borderlands. It served as the main port for shipping and commerce for inland cities such as Ciudad Victoria, Monterrey, and towns in between, extending north toward the old Villas del Norte, which by 1848 comprised part of the border between the United States and Mexico.

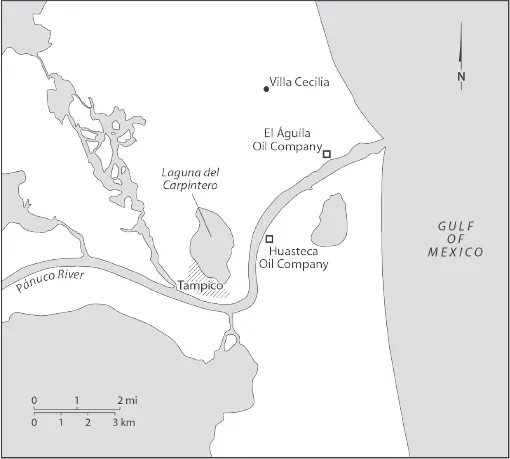

The circulation of such ideas thrived in working-class enclaves including the small town of Villa Cecilia, which served as the home for hundreds, then thousands who descended upon the region. From the southern sector of Tamaulipas and toward its border with Texas, men and women, workers and nonworkers alike, participated in some of the more extreme radical activity of their time, promoting big ideas that had the potential to effect material and political change.1

The roots of anarchist thought date back to at least the French Revolution of the late eighteenth century. These ideas soon reached the Americas.2 The Gulf of Mexico, in particular, shared a long history of transatlantic commerce. Veracruz and Tampico had ties to ports including Barcelona and Liverpool as well as urban centers like Madrid and Paris. Barcelona in particular had a long, rich labor history, and Catalan workers shared manifestos and other writings with their European community, Latin America, and other parts of the world. Barcelona’s emergent working class shared its lived experiences in print editorials and news stories via Tampico and Veracruz. These ideas were diffused in the countryside and further inland, reaching other cities. As various ports and nascent industrial centers witnessed growth, ideas about labor justice and autonomy became increasingly represented in writings by anarchists, further influencing the growing workforce.

Gradually, different strands of anarchist thought emerged. These ranged from the nonviolent anarchism to the branch associated with assassination plots, bombs, and other more destructive forms of expression. During the nineteenth century, anarchism and other radical forms of thought began to make headway in North America. Soon thereafter, it served as the intellectual framework guiding reading clubs, secret societies, and mutual aid groups whose members sought to effect change in their local communities by acting upon such ideology.

Figure 2. Tampico and Villa Cecilia

As the French Intervention came to a close in Mexico in the 1860s, Mexican artisans, workers, and political thinkers forged what would become a more structured labor movement. Labor-focused congresses were organized throughout the country as well as in the capital. Textile, tobacco, and mine workers organized collectives and engaged in some of the earliest strikes in the country. These developments were further strengthened as anarchists fleeing political repression sought refuge in Mexico and shared their own social and political ideas. Greek socialist and anarchist (and, briefly, a Mormon convert) Plotino Rhodakanaty was among the thinkers who migrated to Mexico City. In the capital, Rhodakanaty helped to establish an anarchist organization, La Social, which emphasized “liberty, equality, and fraternity” and sought to create a pan-nationalist movement. He recruited both men and women to the organization. Some Mexican women, including Soledad Sosa, later served as delegates to the first Mexican National Labor Congress as early as 1876.3 The passionate Greek immigrant espoused women’s rights and was among the most progressive of his European anarchist contemporaries regarding women’s issues.4

Other thinkers, such as the Frenchman Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Russian Mikhail Bakunin, helped to spread anarchist thought in its varied forms. By the 1870s Bakunin advocated the abolition of hereditary property, the distribution of land for agricultural communities, and equality for women.5 At the heart of Bakunin’s and other anarchists’ beliefs was the rejection of government and advocacy for collective and individual autonomy. In similar fashion, the ideas of the Italian Giuseppe Fanelli introduced anarcho-syndicalism as a more structured idea that privileged worker unity and autonomy through labor collectives or unions. In Spain, Madrid and Barcelona became hotspots of labor unrest, and Spanish anarchists soon collaborated with Mexican anarchists. Over 300,000 workers sympathetic to anarcho-syndicalism founded the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo in 1910 and joined forces with the Federación Anarquista Ibérica.6 The founding of such collectives was possible given the continuous outpouring of ideas from anarchist and anarchist-sympathetic communities and individuals that shook the status quo.7

Conditions for women workers in Barcelona resembled those in increasingly industrialized and urban centers in Mexico. All-female labor associations emerged in the Spanish port to address growing economic inequalities and provide mutual assistance. These included the Sociedad Progresiva Femenina, the Federación Sindical de Obreras, and the Secció Mútua Feminal del Centre Autonomista de Dependents del Comerçi de la Industria.8 Spanish anarchists, like other European contemporaries, helped to spread the ideas of Barcelona native Francisco Ferrer i Guardia, whose influence profoundly shaped the Mexican labor movement.9

By the turn of the twentieth century, mining centers, smelters, railroad worksites, and other industrial establishments expanded, particularly in the Mexican North, with a corresponding increase in free wage labor that shaped the contours of the Porfirian politico-economic system. While the “existence of wage workers alone did not imply the existence of a proletariat,” the combination of such changes in labor systems with sharp divisions based on wage inequality and—for export-driven sectors like Tampico—the presence of foreigners and attendant industrial workers gave rise to a “collective group identity.”10 This shared experience became further radicalized as workers were exposed to anarchist ideas that had the potential to radically change people’s outlook and effect material change. Such potential to alter the status quo made anarchy an attractive ideology in Mexico, best represented in magonismo by the first years of the century.

As Mexican historiography has shown, much of the discontent in the country grew from years of subjection to a dictatorship that limited people’s political and labor rights. Porfirio Díaz cracked down on early labor organizing, much of it tied to anarchist and other socialist activity. Despite his shutting down presses and imprisoning opposition thinkers and activists, the critique continued underground. Mexicans’ discontent with Díaz received support from labor organizations abroad. For example, Páginas Libres, a Barcelona proworker newspaper, reprinted correspondence from Mexican organizations, and editorials reflected its solidarity with Mexican workers, showcasing their support for a global working class. Páginas Libres’ editorial team took pride in publishing commentaries on the abuses committed by Díaz. As one story put it, “Porfirio Díaz is simply a jackal … a monster, thirsty for blood, always seeking greatness.”11 Newspapers such as Páginas Libres as well as the local anarchist press played a critical role in the early spread of ideas about political and labor rights. They provided an outlet for the ideas of Flores Magón and his supporters, who became known as magonistas. Páginas Libres and Rebelde from Barcelona as well as scores of other proanarchist, proworker periodicals circulated throughout Europe and the Americas. Their news and commentaries were reprinted in the main magonista outlet, Regeneración, as well as Tampico and Villa Cecilia–based newspapers. These periodicals—either full issues or specific news clippings—made their way across the Atlantic, shared among activists and between organizations, carried via ship by workers and others as well as through regular mail.

Villa Cecilia and Tampico: A Home for Anarcho-Syndicalists

Villa Cecilia and Tampico became a hub of anarcho-syndicalist activity by the early twentieth century. Villa Cecilia, about four miles from the port of Tampico, was named for wealthy widow Cecilia Villarreal. After her husband Manuel Casados died, Villarreal donated land for the townsite and soon the small ranchería quickly expanded, reaching villa status. The town maintained close ties to poblados such as Árbol Grande that expanded as oil explorations intensified by the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In 1885, the governor of Tamaulipas, Rómulo Cuellar, authorized California investor Edward Doheny to install a planta perfeccionadora, the first oil processing site in the Mexican republic. Tampico had both a geological and geographic advantage. It was part of the faja de oro, or gold belt, along the Gulf of Mexico with rich oil deposits. The port also offered petroleum corporations a reliable transportation system via its waterways. It was the perfect investment venture. A newsletter for oil investors in the United States described the region's transport advantages: "Tampico is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Terminology

- Abbreviations Used in the Text

- Timeline

- Introduction: Reenvisioning Mexican(a) Labor History across Borders

- 1 The Circulation of Radical Ideologies, Early Transnational Collaboration, and Crafting a Women’s Agenda

- 2 Gendering Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalist Organizations: “Compañeras en la Lucha” and “Women of Ill-Repute”

- 3 Feminismos Transfronterizos in Caritina Piña’s Labor Network

- 4 The Language of Motherhood in Radical Labor Activism

- 5 “Leave the Unions to the Men”: Anarchist Expressions and Engendering Political Repression in the Midst of State-Sanctioned Socialism

- 6 A Last Stand for Anarcho-Feminists in the Post-1920 Period

- 7 Finding Closure: Legacies of Anarcho-Feminism in the Mexican Borderlands

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access For a Just and Better World by Sonia Hernandez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Mexican History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.