![]()

1

LOST CIVILISATIONS

IN 1856, A CONTRACTOR NAMED WILLIAM BRUNTON, working on the Multan to Lahore railway, found the perfect source for track ballast to construct embankments. At the small village of Harappā he discovered thousands of uniformly shaped kiln-fired bricks buried in a series of mounds that locals had been excavating to obtain building material for their houses. The news eventually reached Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893), the founder of the Archaeological Survey of India, who, in 1873, surveyed an extensive series of ruins almost a kilometre long running along the banks of the Ravi River. He assumed they were the remains of a Greek settlement left behind by Alexander the Great’s army in the fourth century BCE. So much of the rubble had been cleared away he decided that there was little worth preserving, leaving the most significant discoveries for future archaeologists.

Among the artefacts Cunningham did collect was a small seal, not much bigger than a postage stamp, made of smooth black soapstone and bearing the image of a bull with six characters above it. Because the bull had no hump and the characters did not resemble the letters of any known Indian language, he believed the seal came from elsewhere. Other seals were gradually uncovered featuring animals such as elephants, oxen and rhinoceroses – and mysterious characters.

Some of the seals made their way to the British Museum, where one, depicting a cow with a unicorn-like horn, features in Neil MacGregor’s 2010 book, A History of the World in 100 Objects. As the museum’s former director notes, the tiny seal would lead to the rewriting of world history and take Indian civilisation thousands of years further back than anyone had previously thought.

Originally thought to be a unicorn, the animal on this seal is now believed to be a bull. The seals of the Harappān civilisation contain the oldest writing in South Asia. It has yet to be deciphered.

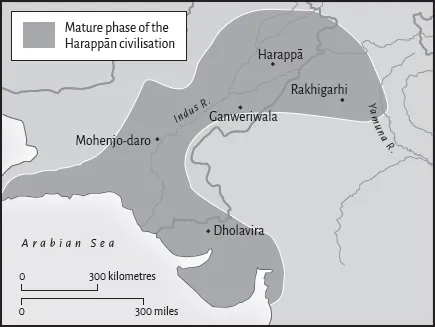

It was Cunningham’s successor, Sir John Marshall (1876–1958), who recognised the significance of the seals. In the 1920s, he ordered further excavations at Harappā and a site that came to be known as Mohenjo-daro, or ‘Mound of the Dead Men’, several hundred kilometres to the south in what was then British India and is now the province of Sindh, in Pakistan. Marshall realised immediately there was a link between the two sites. At both places there were numerous artificial mounds covering the remains of once-flourishing cities. As dozens of similar sites came to light over an area stretching from the Yamuna River in the east to present-day Afghanistan in the west, it became clear that between roughly 3300 BCE and 1300 BCE, it had been home to the world’s largest civilisation (by area).

Until Marshall’s discoveries, there was no material evidence of any Indian civilisation that predated Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE), whose conquering armies reached the shores of the Indus River in 326 BCE. Almost all of the archaeological remains from around this date were Buddhist, with much of the statutory bearing Grecian influences.

Map showing Mature Phase of the Harappān civilisation, also known as the Indus Valley civilisation. The former, named after the first discovered site, is now preferred because the civilisation extended beyond the Indus River.

As Marshall continued his excavations, he was stunned by the uniqueness of the finds. To begin with, those prized bricks turned out to be remarkably uniform across all the excavated sites. The settlements were built on similar grid layouts, with street widths conforming to set ratios depending on their importance. There were imposing communal buildings, what appeared to be public baths and a sophisticated sanitation system – triumphs of town planning, far in advance of anything known in the ancient world and not to be repeated in India until Maharaja Jai Singh I laid out plans for Jaipur in the early eighteenth century. Even the weights and measures used in trade were remarkably uniform.

Toys and figurines made of clay and bronze, jewellery and cooking aids, rudimentary agricultural tools, fragments of painted pottery, whistles made in the form of hollow birds, and even terracotta mousetraps were found at dozens of sites. Then there were those seals – almost 5000 have been discovered so far – some with anthropomorphic figures, others with animals including that mysterious unicorn-like bovine in the British Museum. ‘Not often has it been to archaeologists, as it was given to Schliemann at Tiryns and Mycenae, or to Stein in the deserts of Turkestan, to light upon the remains of a long-forgotten civilization. It looks, however, at this moment, as if we were on the threshold of such a discovery in the plains of the Indus,’ Marshall announced triumphantly in September 1924.

We now know that at its peak in 2500 BCE, around the time the Great Pyramid of Giza was completed and a century or so before Stonehenge rose from the fields of Wiltphire, the Harappān civilisation covered an area of more than a million square kilometres, making it bigger than the civilisations of Egypt and Mesopotamia combined. But unlike our knowledge of its better-known contemporaries, what we know of this momentous civilisation is scanty. No Rosetta Stone has been discovered to crack the code of those ubiquitous markings on the seals.

Over the past century and a half, attempts to identify the characters by linking them to scripts or languages as diverse as Brāhmī (the ancestor to most modern South Asian scripts), Sumerian, Egyptian, Old Slavic and even Easter Island rongorongo have proven futile. Citing the brevity of most inscriptions (fewer than one in a hundred objects with ‘writing’ have more than ten characters), some historians and linguists have speculated that the seals do not contain script at all but are devices that denote ownership – a primitive form of a barcode.

If this was a form of writing, it would make the Harappān civilisation the largest literate society of the ancient world, and arguably its most advanced. It would not be until the reign of Emperor Aśoka in the third century BCE that evidence of writing emerged on the Indian subcontinent. Unless archaeologists stumble upon a buried library or archives, the mystery of the script, if indeed that is what it is, will remain just that.

In their attempt to establish a chronology of the Harappān civilisation, archaeologists have made little headway in determining how the society was governed and functioned. None of the structures appeared to be palaces or places of worship. Fortifications weren’t added until the later phase of the civilisation, and few weapons have been unearthed. The lack of elaborate burial places suggests a degree of social equality found nowhere else in the ancient world. Evidence of a ruling class with kings or queens has yet to established.

Based on the discovery of seals as far afield as Iraq, Oman and Central Asia, it is clear that this was also a significant trading empire. Copper, gold, tin, ivory and possibly cotton were traded with Mesopotamia, while bronze, silver and precious stones such as lapis lazuli were imported. Yet after a century of excavations, considerable uncertainty remains over how this prosperous and sophisticated civilisation was founded and what caused it to vanish.

In the absence of definitive evidence, numerous theories have filled the vacuum. The race to decipher the script has led to forgeries, including the doctoring of an image on a seal to make it look like a horse, an animal of considerable importance in Vedic ritual. Most of these forgeries have been constructed around the need to provide a continuous line to the foundation of the modern Indian state. In recent decades, Hindu nationalist historians have sought to incorporate the Harappān civilisation with the beginnings of Hinduism that they argue dates back to the third or fourth millennium BCE, thereby making it the oldest religion in South Asia.

THE EARLIEST INDIANS

If the archaeological discoveries of the early 1920s were a watershed in pushing back the beginnings of Indian civilisation by thousands of years, the 2010s will be remembered for the astonishing advances in our understanding of the ancestry of the earliest Indians. The ability to analyse the genetic DNA of skeletal remains has enabled scientists to map migration routes into India, identify the first agriculturalists and even date the beginnings of social stratification known as the caste system.

Based on archaeological finds, such as beach middens in Eritrea, we can confidently date the migration of modern humans, or homo sapiens, out of Africa to around 70,000 years ago. Their route took them through the Arabian Peninsula and across modern-day Iraq and Iran, until they reached the Indian subcontinent some 65,000 years ago. There, they encountered groups of what are termed ‘archaic humans’. In the absence of any fossil evidence other than a cranium discovered on the banks of the Narmada River and dated to approximately 250,000 years ago, we do not know who these people were. The discovery of Palaeolithic tools in South India pushes back the timeline for these archaic people to 1.5 million years ago, making them one of the earliest populations outside Africa. As modern humans settled in the more fecund areas of the subcontinent, their population increased rapidly until India became the epicentre of the world’s population during the period from approximately 45,000 to 20,000 years ago.

DNA dating points to a second wave of migrants who made their way eastwards from the southern or central Zagros region in modern-day Iran around 8000 BCE. The precursor to what became the Harappān civilisation can be found in a village so remote and obscure that even people living in the area don’t know of its existence. Mehrgarh is located in the Pakistani province of Baluchistan, a lawless tribal area on the western edge of the Indian subcontinent. Archaeologists digging at the site in the late 1970s found the earliest evidence of agriculture outside the Fertile Crescent. Crops such as barley were cultivated, and animals including cattle, zebu and possibly goats were domesticated. Buildings ranged in size from four-to ten-roomed dwellings, with the larger ones probably used for grain storage. Buried alongside the dead were ornaments made from seashells, lapis lazuli and other semi-precious stones. Archaeologists discovered the world’s first examples of cotton being woven into fabric.

By the time it was abandoned in favour of a larger town nearby sometime between 2600 and 2000 BCE, Mehrgarh had grown to become an important centre for innovation not only in agriculture but also in pottery, stone tools and the use of copper. The agricultural revolution it sparked would become the basis of the Harappān civilisation.

THE WORLD’S FIRST SECULAR STATE?

Historians divide the Harappān civilisation into three phases. The Early Harappān, dating from around 3300 to 2600 BCE, was proto-urban. Pottery was made on wheels, barley and legumes were cultivated, and cattle, sheep, goats, buffalo, deer and pigs were domesticated. The civilisation was extensive – remains from this period have been found as far west as the Indo-Gangetic Plain, and south to the Rann of Kutch, in modern Gujarat state. However, there is much about this phase that is unknown. At sites such as Mohenjo-daro, the ruins extend several metres below the current excavation depth, but with preservation taking precedence over excavation it may take many years before a more definitive picture of this period emerges.

The Mature Harappān phase, dating from 2600 to 1900 BCE, is considered the peak of urbanisation, though villages still outnumbered urban centres. The positioning of citadels, granaries, public and private buildings varied across the settlements, but all, from the biggest to the smallest, had some degree of planning. Irrigation works were sophisticated enough to allow a succession of crops to be grown; ploughs were used to cultivate the fields. Skeletal remains of dogs suggest their domestication. The population estimate for the Mature phase ranges from 400,000 to one million people.

While the absence of any evidence of large royal tombs, palaces or temples, standing armies or slaves, mitigates against the idea of a centralised empire, some form of state structure likely existed. The uniformity in crafts such as pottery and brickmaking down to the village level suggests specialised hereditary group or guilds, and a well-developed system of internal trade. By the Mature phase, the symbols that were found on seals became standardised. Gambling was widespread, as evidenced by dozens of cubical terracotta dice discovered at Mohenjo-daro and other sites. Cotton was cultivated for clothes and possibly traded with West Asia.

Although no structures that can be definitively classified as temples have been discovered, some kind of religious ideology almost certainly existed – the links between what is known of Harappān systems of belief and the development of Hinduism are too numerous to ignore. Images of what could be deities in peepal trees with worshippers kneeling in front of them were common (the tree is considered sacred in both Hinduism and Buddhism). Bathing, an important part of Harappān civilisation, is a centrepiece of Hindu ritual. The existence of what appear to be fire altars, evidence of animal sacrifices and the use of the swastika symbol recall Hindu ceremonies.

The most compelling evidence of a link is a seal depicting a figure seated in a yogic position wearing a horned headdress and surrounded by a tiger, elephant, buffalo and rhinoceros. The figure on the inch-high seal was named Pashupati or ‘Lord of the Beasts’, and was described by Marshall as a ‘proto-Śiva’, or early model of Śiva – a key deity in the Hindu pantheon, considered the god of creation and destruction.

But as the American Indologist Wendy Doniger points out, the Śiva connection is just one of more than a dozen explanations for the figure ‘inspired or constrained by the particular historical circumstances and agenda of the interpreter’. Similarly, small terracotta statuettes of buxom women could be prototypes of Hindu goddesses or mere expressions of admiration for the female form. What we do know is that the migrating tribes from Central Asia drew on existing deities and belief systems. If these alleged deity prototypes were not evidence of a coherent religious system, they open up the tantalising possibility that the Harappān civilisation may have been the world’s first secular state, predating the European Enlightenment by four millennia.

The description of the Lord of the Beasts seal as a proto-Śiva was eagerly embraced by Jawaharlal Nehru and subsequently by Hindu nationalist historians.

What caus...