eBook - ePub

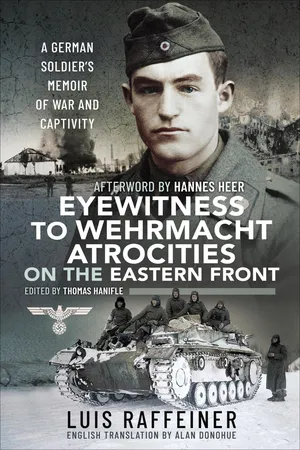

Eyewitness to Wehrmacht Atrocities on the Eastern Front

A German Soldier's Memoir of War and Captivity

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Eyewitness to Wehrmacht Atrocities on the Eastern Front

A German Soldier's Memoir of War and Captivity

About this book

A German soldier deployed to Russia recounts his harrowing experience as both victim and perpetrator of Nazi atrocities in this WWII memoir.

Serving his country on the Eastern Front, Luis Raffeiner witnessed devastating acts committed by the German army that couldn't be reconciled with the heroic propaganda back home. Caught up in the turmoil of the vast conflict, he struggled to make sense of the ruthlessness he witnessed—and the part he himself played in it. In this bracingly candid memoir, Raffeiner offers a detailed firsthand account of the Nazi war of annihilation in the Soviet Union.

Raffeiner chronicles his family life in a remote village in the Tyrol in the 1930s, his military service in Italy, his transfer to the Wehrmacht and his training as a mechanic on assault guns. He then proceeds to his march into the Soviet Union in 1941. There he experienced, as he says, 'war in its brutal and cruel reality'.

Captured by the Red Army, Raffeiner barely survived as a prisoner of war. His dramatic and honest recollections shatter the myth of the clean conduct of the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front. He testifies to vicious actions, including some in which he himself was involved. His memoir is not a heroic tale – it shows how a man from an ordinary background can come to participate in the horrors of war.

Serving his country on the Eastern Front, Luis Raffeiner witnessed devastating acts committed by the German army that couldn't be reconciled with the heroic propaganda back home. Caught up in the turmoil of the vast conflict, he struggled to make sense of the ruthlessness he witnessed—and the part he himself played in it. In this bracingly candid memoir, Raffeiner offers a detailed firsthand account of the Nazi war of annihilation in the Soviet Union.

Raffeiner chronicles his family life in a remote village in the Tyrol in the 1930s, his military service in Italy, his transfer to the Wehrmacht and his training as a mechanic on assault guns. He then proceeds to his march into the Soviet Union in 1941. There he experienced, as he says, 'war in its brutal and cruel reality'.

Captured by the Red Army, Raffeiner barely survived as a prisoner of war. His dramatic and honest recollections shatter the myth of the clean conduct of the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front. He testifies to vicious actions, including some in which he himself was involved. His memoir is not a heroic tale – it shows how a man from an ordinary background can come to participate in the horrors of war.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Eyewitness to Wehrmacht Atrocities on the Eastern Front by Luis Raffeiner, Thomas Hanifle, Alan Donohue in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Monastery cell number 10

I was born in monastery cell number 10 in Karthaus/Certosa in the Schnalstal/Val Senales, a side valley of the Vinschgau/Val Venosta. It was in a monastery cell because the village had been built within the walls of the Carthusian monastery Allerengelberg. For four centuries, until the end of the eighteenth century, the devout Carthusian monks had lived here in twelve cell houses. That is why Karthaus is still commonly referred to today as ‘Kloster’ (monastery). My father’s name was Josef Raffeiner and he was a son of the Oberleithof from Vernagt/Vernago near Unser Frau/Madonna di Senales in the far end of the Schnalstal. From a cousin he inherited the aforementioned ‘friar’s cell’ in Karthaus and the small monastery mill by the stream below the village. Thus, he became the new ‘monastery miller’ and could count himself lucky, because whoever did not own anything had no choice but to become a day labourer. In addition, the Church would not allow somebody to marry if they could not support a family. So father took over the little house and mill and asked Aloisia Kofler from the Mühlhof in Katharinaberg/Monte Santa Caterina if she would be his wife. The wedding took place in Karthaus on 1 April 1912.

As a result, my mother brought a total of six children into the world: Josef in 1913, Anton the following year, and Maria in 1915. It was on 23 July 1917 when I first saw the light of day. In the summer of 1919, the year South Tyrol was officially annexed to Italy, our mother finally had the twins Luise and Peter. But none of our lights shone particularly brightly. I do not mean the fact that there was no electricity, only kerosene lamps, in our case the particularly economical ‘Salzburg’ lamps. ‘Minimalism’ reigned in every respect: with regard to food, clothing and especially money. It also did not help that my father did not have to go to fight in the First World War – he was the only miller in the village and therefore indispensable – as our little mill did not bring in much anyway. There was barely enough to live on for the family of eight. People had their grain milled, and often the work was only rewarded with a ‘thank you’ as they had little themselves.

Karthaus in the Schnalstal. Before the fire, the Raffeiner family lived in the house that was monastery cell number 10 (to the right of the church, the first house of the group of three in the picture).

In Karthaus there was only one big farmer, called Sennhofer, who grew grain himself. His farm stands majestically above the village with a view far into the valley. People used to bypass his grain field with their cows, who would use the edge of the field to turn. This strip of land, the so-called ‘Onawond’, was leased to my father for mowing. In return, he had to mill Sennhofer’s grain. People lived more or less through such barter. Because my parents did not even have enough land to support feeding a cow, they had to carry some of the hay home in racks on their backs. They even fetched the feed from the Vorderkaser, a farm in the neighbouring Pfossental valley. The entire effort to look after a few domestic animals was enormous.

My parents owned a cow, two goats, a few chickens, a pig and, in addition to the garden behind the house that had already served the monks, a very small uneven piece of land on the edge of the forest above the Sennhof. Our two goats grazed up there on the steep terrain. Our cows, on the other hand, were housed in a stable on the village square. The associated dung heap was certainly no ornament for the village square and probably bothered one or two people, but it was not the only one.

We used the manure as fertilizer for the meadow and garden: my mother mainly planted broad beans, cabbages and potatoes there. Since Karthaus lies above 1,300 metres, not much grew there. And vegetables like tomatoes were not even known yet back then. My mother got the cabbages from Platthüttl, a farm that lies between Karthaus and Neuratheis. At that time these vegetables grew much taller than they do today and only had a very small head. Each family had a barrel in which cabbage and beets were stored as sauerkraut for the winter. To the poor inventory of every household also belonged a Stinkölbundel, a kind of container which could be filled in the only shop in the village with kerosene for the lamp.

The village square in Karthaus. The Raffeiner family also had their stables and dung heaps there.

The bread was bought at the bakery, as only the farmers had their own oven. My mother used the grain – barley, oats and rye – to make soups and also ‘mash’, a nutritious porridge made from milk and flour. For the morning and evening meals there was either mash or a very thin Brennsuppe (flour soup): because it was so thin, we called it Wosserschnoll (water lumps). For lunch there was either potatoes, polenta, dumplings or barley soup. People usually ate from a pan that was placed in the middle of the table and from which everyone spooned out their food following a prayer.

The pig was slaughtered just before Christmas. The main part of it was smoked, and thus preserved in this way. Throughout the winter there was mostly cabbage and some meat, and only at Christmas even doughnuts filled with chestnuts and baked in pork fat. Unfortunately the portions were always too sparse for the whole family. By July or August the last bit of bacon was gone and we had to console ourselves with the thought of next Christmas.

My mother, like all other women at the time, did not have it easy: raising six children, tending to the garden, looking after the animals, and washing dirty clothes by hand. The few items of clothing that people owned at the time had to be constantly mended so that the younger siblings could reuse them. Only on Sundays was mending clothes not allowed. There was a saying for women and girls: ‘Sunday stitches burn you!’ By this was meant hell-fire. Sunday was very important, sacred, and the Church generally had a great influence on people’s lives. After each birth my mother had to go to church for a blessing because women were considered impure following a birth. Even at the church door the priest began the elaborate ritual that helped the woman to regain her status of purity.

On Sundays the men met in the tavern after mass. There were two in the village: the Rosenwirt and the Kreuzwirt. My father was not much of an inn-goer and did not care much about politics either, which people liked to bluster about there. He often held back with his opinions, even when Italian fascism, with all its consequences, gradually established itself in the valley and in Karthaus too. He carried out the prescribed Sunday duties and on weekdays he worked in the mill. When a small power station was built next to our mill in 1923 to supply the village with electricity, my father took over care of it. He was happy about the additional income, even if it was only small. His parenting technique was simple and efficient, like my mother’s: ‘If you don’t obey, you don’t get anything to eat!’ That usually helped.

Luis Raffeiner with his childhood friend Bernhard Grüner (left). Grüner later became a staunch Nazi and functionary with the VKS, the Völkischer Kampfring Südtirols (a Nazi organization in South Tyrol).

Back of a photo. The friendship broke down during Raffeiner’s leave from the front in July 1942, when Raffeiner expressed his opinion about the imminent defeat of Germany and thus aroused Grüner’s hatred.

We children, of course, also had our duties. In addition to feeding the chickens we were responsible for the kindling. It was arduous work: we had to go up into the forest again and again, and the path was long and steep. The small amount of wood that we brought home was quickly used up again. From time to time we also took Haislstreib with us. These needles that had fallen from the forest trees were needed as litter for the outhouse.

We children mainly met on the village square to play. Tag and hide-and-seek, teasing, but then also scuffles were the order of the day. I preferred to hang around with Bernhard Grüner, and sometimes his sister Marianne also played with us. As a child I could not have known that this friendship with Bernhard would end tragically.

Chapter Two

A fire and its consequences

On 21 November 1924 a devastating catastrophe occurred in Karthaus. It was around 10.30pm and I was already in a deep slumber on my straw mattress when I was torn from my dreams with the words ‘Up, up, it’s on fire!’ I did not understand at all what was going on. I stumbled out of bed, half asleep. My sister Maria helped me into my clothes. Hectic instructions were shouted back and forth, the most essential things were hastily gathered together upstairs and downstairs. I stood there being pushed aside because I was in the way. Suddenly Maria pressed something under my arm too, and I was chased out of the door with my other siblings. Outside I heard excited voices, the roaring of animals, steps on the stones of the monastery corridor, and dogs barking. Lantern lights flitted about, there was mass confusion. There was no time to look. By now I had understood what was going on. I was taken outside the monastery wall along with the other children. Father had assigned us a place below the village where the wall was highest. After he had retrieved the cow from the stable he hurried back to rescue the pig. When he got to the stable the roof beams had already caught fire, as he later told us. An Italian tax official tried to stop him from getting the pig, but my father pushed the man roughly aside and rescued our pig from the burning pen.

Meanwhile, I waited with my mother and siblings below the village. The high wall that protected us also blocked our view of what was happening. All you could see was the glow of the fire, which illuminated the night. The wind carried wisps of voices, crackling, and cracking down to us, sparks floated into the valley, and the smell of burning impregnated the air. Suddenly it shot into my head and would not give me any peace: I absolutely had to know if our house was also on fire. While Mother was busy with the younger siblings, I hurried along below the wall until I came to the place where there was a gap in the wall. From here I could see the flames that blazed from the houses. And yes, our house was on fire. I breathed a sigh of relief. ‘Thank God, it was burning!’ There was one thing that had been weighing on my young mind for a long time. For father owned a silver pocket watch, a beautiful heirloom, that he only wore on very special occasions. It must have been very valuable to him because he had forbidden us under the strictest threat of punishment to touch this watch. But I was an inquisitive rascal, and my curiosity was simply stronger than my reason. One fine day I gave the watch a thorough inspection with my pocketknife. With the tip of the small blade I unscrewed the tiny little screws. The cogwheels were so thin and delicate – I was fascinated by this technical marvel. So I disassembled the whole watch with the intention of putting it back together properly. Unfortunately my honest endeavours were not crowned with success. My ears burned when, after trying in vain, I put the dismantled corpus delicti back in my father’s box. Since then I had been tormented by my conscience and even more so by the fear of punishment. So I was very relieved when I saw the flames because they obliterated the traces of my deed. That was my personal, childish perspective of this dramatic event. I was not aware of the actual implications of the flames. Not yet.

On 21 November 1924 the entire village burned down and the Raffeiner family lost everything.

Back with my family, we spent the night there and then outdoors. It was the last hours of our being together. The fire had caused a devastating catastrophe that night: the whole village burned down except for a few houses, and the church also fell victim to the flames. Many animals could not be saved and perished wretchedly in the fiery hell. Two elderly people were killed in the fire, another died a few days later as a result of the fire. The cause of the fire has not been fully clarified to this day. Homeless and deprived of their few belongings, many families were close to despair. Many had relatives who offered shelter for the time being, but afterwards most families were torn apart.

In our case, the two youngest siblings, Luise and Peter, found pitiful shelter with our parents in the small mill below the village. In the mill there was only a small, secluded room, the Mühlstübele (little mill room). My mother slept with the twins in this neatly...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword: Talking about the war, by Thomas Hanifle

- 1. Monastery cell number 10

- 2. A fire and its consequences

- 3. Fascist harassment

- 4. Youthful exuberance

- 5. Germany sounded more promising

- 6. Warm greetings from Gauleiter Hofer

- 7. Training as a tank mechanic

- 8. Crimes against humanity

- 9. In the Jewish ghetto

- 10. War knows no mercy

- 11. End of a friendship

- 12. Attack on Stalingrad

- 13. Calm before the storm

- 14. ‘Run, Raffeiner, the war is over’

- 15. ‘The dead can’t harm us’

- 16. Journey into captivity

- 17. The struggle for survival

- 18. A research hospital?

- 19. Free at last

- 20. My new life

- Afterword: ‘Show your wound’, by Hannes Heer

- Notes