- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

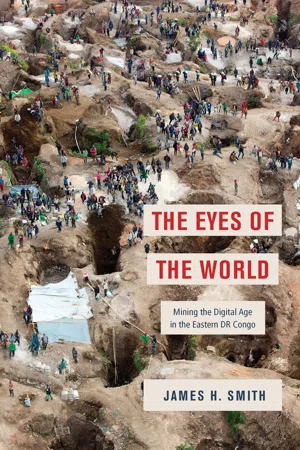

The Eyes of the World focuses on the lives and experiences of Eastern Congolese people involved in extracting and transporting the minerals needed for digital devices.

The digital devices that, many would argue, define this era exist not only because of Silicon Valley innovations but also because of a burgeoning trade in dense, artisanally mined substances like tantalum, tin, and tungsten. In the tentatively postwar Eastern DR Congo, where many lives have been reoriented around artisanal mining, these minerals are socially dense, fueling movement and innovative collaborations that encompass diverse actors, geographies, temporalities, and dimensions. Focusing on the miners and traders of some of these "digital minerals," The Eyes of the World examines how Eastern Congolese understand the work in which they are engaged, the forces pitted against them, and the complicated process through which substances in the earth and forest are converted into commodified resources. Smith shows how violent dispossession has fueled a bottom-up social theory that valorizes movement and collaboration—one that directly confronts both private mining companies and the tracking initiatives implemented by international companies aspiring to ensure that the minerals in digital devices are purified of blood.

The digital devices that, many would argue, define this era exist not only because of Silicon Valley innovations but also because of a burgeoning trade in dense, artisanally mined substances like tantalum, tin, and tungsten. In the tentatively postwar Eastern DR Congo, where many lives have been reoriented around artisanal mining, these minerals are socially dense, fueling movement and innovative collaborations that encompass diverse actors, geographies, temporalities, and dimensions. Focusing on the miners and traders of some of these "digital minerals," The Eyes of the World examines how Eastern Congolese understand the work in which they are engaged, the forces pitted against them, and the complicated process through which substances in the earth and forest are converted into commodified resources. Smith shows how violent dispossession has fueled a bottom-up social theory that valorizes movement and collaboration—one that directly confronts both private mining companies and the tracking initiatives implemented by international companies aspiring to ensure that the minerals in digital devices are purified of blood.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Eyes of the World by James H. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Orientations

Prologue

An Introduction to the Personal, Methodological, and Spatiotemporal Scales of the Project

This prologue is intended to give a broad overview of the project—mainly, the general topic and the changing historical context in which this longitudinal research took place (carried out mostly in three-month periods between 2006 and 2018). It consists of a brief narrative regarding the motivation for the research and how it was conducted, followed by some relevant (no doubt inadequately represented) history that is punctuated by a revealing fieldwork vignette quickly capturing some important themes that framed the research context. A more detailed discussion of the book’s main arguments is found in chapter 1.

The Eyes of the World explores the worlds of artisanal mining in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), examining how decades of violent colonial and postcolonial war and exclusion have, in producing dispossession, also encouraged the emergence of a multidimensional extractive economy oriented around fostering movement and collaboration among very different actors, elements, arrangements, and modes of life. The main focus is on the work, lives, and concepts of miners and traders of what I sometimes refer to as “digital minerals” and what Congolese in the Kivu provinces and Maniema province call the “black minerals” (minéraux noire) and sometimes “coltan” (though coltan is also the Congolese term for a specific ore). The collaborative work of people involved in this trade connects Congo with places like Silicon Valley in ways that are counterintuitive and concealed (there are currently an estimated two million artisanal miners in Congo, and it has been estimated that ten million people depend on artisanal mining, although not all of these are mining the black minerals; see Garrett and Mitchell 2009).

Coltan is the colloquial term for a silicate essential to the capacitors used in all digital devices, including mobile phones (Nest 2011). It contains tantalum and niobium, elements named after mythological Greek Titans who were punished for their defiant hubris against the gods—an ironic naming, given that the technologies these minerals enable have helped give rise to a putatively “posthuman age” in which people strive to take on some of the characteristics of superior beings, including immortality and omniscience (Hayles 1999).1 Their material density enables these elements to hold a high electrical charge, allowing for ever-smaller digital devices (as we will see, most Euro-Americans see smallness as a product of the ingenuity of Silicon Valley engineers, or the sui generis evolution of technology itself, rather than as substances and the work of extracting and moving them). Coltan is similar in appearance to and, in Congo, is often found alongside other “black minerals” that are equally crucial for digital technologies, especially wolframite, the ore from which tungsten is derived, and cassiterite, from which tin is derived. Tungsten is used to make computer screens, and it also enables cell phones to vibrate; tin is used in wiring, among many other processes. Eastern Congolese diggers don’t specialize in these substances but move among them based on a number of different factors, including what seems to be in demand at any given time. International nongovernmental organizations have come to call these minerals the “3Ts” (tantalum, tin, and tungsten); in recent years, they have been the target of a great deal of humanitarian discourse and intervention.

A Brief Biography of This Project

If I were to look deeply into myself, I suppose part of what first intrigued me about the mining of Congolese coltan was my deep, emic familiarity with and dislike of techno-utopianism and technosolutionism. I grew up in the 1980s near a Massachusetts tech corridor, and all of my high school friends—even the poets—eventually became computer programmers or software developers. They did this partly because that’s what people who were deemed to be smart did then and there and because computerization and technology seemed to be where the future lay—it was world transformative, and that was exciting to people, especially young people (and, I suspect, especially males) who felt smart enough to ride this wave into the future. Computers also allowed young men who were not encouraged to practice humanistic arts to be creative; and it was where the money seemed to be. This wouldn’t have been so bad in and of itself, but even then, I found that the embrace of technology as the engine of the future and the solution to all the world’s problems tended to go hand in hand with a derisive or dismissive attitude toward the concepts and ways of life of those who were deemed to be less technologically “developed.” This attitude of dismissiveness usually also extended to everything deemed to be somehow “old.”

Later on, I witnessed a vernacular version of this techno-utopianism emerging in Kenya during the 1990s and early 2000s. It was directed against the old men of Kenyan politics, with their focus on what, for urban elites, were outmoded issues like land, and it envisioned a future that moved beyond what some Kenyans would eventually call “analogue politics” (Poggiali 2016, 2017; Nyabola 2018). Eventually, I moved to Northern California, settling in the interstices between the self-congratulatory techno-hub of the Bay Area and the agri-capitalist Central Valley, and witnessed techno-utopianism and its attendant dismissiveness toward that which lay outside of it on a whole new level, with different inflections. Always there was what anthropologist Johannes Fabian referred to as the “denial of coevalness”—the unwillingness to see that which lay outside of the explicitly “technological” as being as equally contemporary as the technological and as part of the same historical totality that produced the technological in the first place (1986).

When I found out that coltan, an ore found in Congo that seemed to be somehow related to the conflicts there, was essential to all digital devices, it was revelatory for me, as it was for many; I unpack some of the implications of this revelation in chapter 1 and delve into some of the nuances of the war below and in chapter 2. It was also familiar because it spoke to a more global disjunction between the self-presentation of capitalist “progress” and its conditions of possibility. Though it was a radically different context, when I was a youth, anhydrous ammonia sales was our family business (one time, an ammonia tank burst open in my father’s face, suffocating him and leaving him with third-degree internal and external burns that nearly killed him); before my father, it had been bottom-of-the-chain coal extraction and transportation. And one of my siblings started his career in oil extraction at pretty much the lowest level of the process: painting and repairing oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico in his late teens. So, like many, I always knew something about the power of the effectively invisible, sometimes widely unknown, substances that make “modernity” possible and how they could change people’s realities and social situations quickly and dramatically, often with great—even potentially fatal—attendant risk.

I had heard about the devastating Congo wars and the war economy that included Congolese coltan while I was still in grad school. But my first visit to Congo was by myself in 2003, a year after receiving my PhD. I took the one-hour flight from Kenya to Rwanda, followed by a two-hour bus ride to Goma, North Kivu, which at the time was still occupied by a Rwandan-backed militia, the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD); crossing the border meant dealing with soldiers in tents. It was weirdly serendipitous that, en route to the border from Kigali, I happened to be seated next to a Congolese coltan trader (I will call him Michael). Michael became my friend for a while, showing me Goma (which had recently been burned to the ground by the nearby volcano) and Bukavu and introducing me to a lot of people. At that time, the Second Congo War, or Great War, was over in name only (it officially ended while I was in Goma, in July), and it was almost impossible for us to leave the cities of Bukavu and Goma (local transport would not go, and we did not do it). While it was hard for me to learn very much during that month-long visit, I did come to understand that the coltan supply chain was complicated, that it involved a lot of different kinds of actors, and that it would be good to do this work with another anthropologist. I also realized that, in part because of the collapsed infrastructure and the dollarization of the economy, Congo was quite expensive, and I would need a lot more funding to actually carry out research there. (I was happy to learn that I would be able to do the research using my Swahili and that, in the mining areas, Swahili was better than French, of which I had very little.)

Even before that first visit to Congo, I had talked with my friend and colleague Jeff Mantz, who did research on the social life of things, about the prospect of our doing something like what the anthropologist Sidney Mintz (1986) had done for sugar and modernity but with coltan and postmodernity, or the “postmodern” sensibilities that digital technologies helped to produce. (Mintz had brilliantly showcased the interconnectedness of seemingly disconnected parts of the world by following the commodity sugar from the Caribbean to Europe.) After my return, we applied for and received a National Science Foundation (NSF) High-Risk Research grant to conduct preliminary fieldwork on coltan mining in the eastern Congo (the “risk” referred to epistemological rather than bodily risk and was funding to ascertain whether the project was “doable”; see our coauthored piece, Smith and Mantz 2006; also Mintz 1985). In 2006, after spending a summer visiting mines near Goma and Bukavu (the mines near Numbi and Nyabibwe), we decided to divide up research in the following way: I would travel to and work near rural and forest mines, focusing on the extractive work of artisanal miners and low-level traders, while Jeff Mantz would conduct ethnography “higher up” on the supply chain with higher-level négociants (middlepersons) and comptoirs (buying houses) in the cities of Goma and Bukavu. With this division of labor in mind, we applied for another NSF grant, a collaborative one, and set about work. Over time, this developed into two separate research projects.2 Some years later, in 2015, I was awarded another NSF grant to study the impact on artisanal miners of internationally imposed “conflict minerals” regulatory efforts.

Once Jeff Mantz and I had established our division of labor, I set out to do research in Congolese mines and realized that I wasn’t sure exactly where to go or how to do it. I wanted to get a sense of the range of mines that were out there because I was worried about generalizing based on a single place, and my thought was to visit several different locations and then focus in on a few. The only person I had to introduce me to people and places and help me navigate state officials, soldiers, and other situations was Michael, the coltan trader I had met on the bus in 2003. But he was a businessman/trader, and his presence certainly didn’t help persuade people that I was an academic researcher, something people had a hard time with anyway. Moreover, Michael was always trying to redirect me to gold mines because he wanted me to buy gold with him, which at the time was fetching a better price than coltan. So in 2009, at what may have been his suggestion, and certainly with his enthusiastic support, I brought my Kenyan friend, assistant, and colleague Ngeti Mwadime with me to Congo because we were used to working together and I trusted him.3 That worked well enough (we made it to the rainforest mine of Bisie, for one example), and Ngeti was as helpful as he could possibly be, but it became very clear that the main obstacles to doing research in rural Congo were the constant bureaucratic shenanigans from state officials “selling papers,” and Ngeti’s presence didn’t help with that; in fact, because he was also a foreigner, it just compounded the bureaucracy and cost too much money.

In 2011, I was back with Michael again, but by this time he was clearly tired of my not buying gold, and I began to sense that he was trying to set me up to be robbed. (I used to wake up in the morning to see him perched by the side of the bed, staring at me with a pensive look I didn’t like.) On one occasion, we were in a truck together with some former Mai Mai friends (former combatants in an indigenous militia discussed later in this book) of his whom I didn’t know, headed out of Goma, and he asked to be dropped off long before we arrived at our destination, an insecure mining town governed by armed actors. It felt like a setup (all transactions in Congo were in cash, and for a long time, I had no bank account, and even when I had one, there was no way of transferring significant money from one place to another. As a result, I was always carrying large sums of cash, sometimes thousands of dollars, and Michael knew this). But there was another Congolese fellow in the truck with me, who I could tell was just along for the ride. I struck up a conversation with him, and we became fast friends over the course of an hour or so. When the men in the truck were preparing to leave me on my own, I asked him how he’d feel about staying with me for a day or so until I got on my feet. Our suspicions grew when the men in the truck protested, and he insisted on staying (later he confided in me that he stayed because he was concerned for my well-being in this new town). The few days he was to spend with me turned into weeks, then months and years.

The young man in the truck was Raymond Mwafrika (Raymond African, his actual name), and he became my friend and assistant; over the years, we handled many difficult situations, dealt with demanding state figures and “customary authorities,” took cargo planes, and drove many hundreds, even thousands, of miles across Congolese roads in a beater jeep. Much more than an assistant, Raymond was a colleague, because he had a lot of experience with mining, having been involved in local politics in his hometown of Luhwindja, a major artisanal gold-mining town where the Canadian mining company Banro was beginning to extract gold industrially and coming into conflict with the diggers. With a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Bukavu, Raymond also had a good deal of experience working for NGOs and academics. Raymond’s influence, ideas, and interests are strongly reflected in this text. Over time, I helped him grow some more academic connections, and he has assisted other international academics conducting research in Congo.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but through these different moments, I was learning a lot about what I refer to, broadly, as the eastern Congolese practice of “collaborative friendship” that had become so important for people, partly because of the danger and destruction brought about by the war (although this practice was not brought about solely by the war). This practice consisted in forging mutually beneficial friendships with people who were formerly strangers, usually on the fly in moments of crisis, and building enduring networks out of these happenstance alliances. While it seems simple enough, it is a crucial tactic and also a kind of art.

When Raymond and I visited the Institut Supérieur de Développement Rural (ISDR) in Kindu, Maniema, the director introduced us to one of their instructors, Joseph Nyembo, who was also studying the relationship between mining and conflict (he had earned a master’s degree from the University of Brussels and was pursuing his PhD at the University of Kinshasa). Joseph hailed from an old colonial-era company mining town in the rainforest province of Maniema, and his research was there; among other things, he was convinced that foreign researchers had neglected Maniema, the major source of Congolese coltan and other black minerals, because they were focused on the conflict-ridden Kivus on the borders of Rwanda and Burundi. This, he held, had a major influence on how they had thought of minerals and mining as being sources of conflict and destruction rather than peace and what he referred to as “development” (a commonly deployed African term that does not mean the same thing as Western economists imagine it to mean; see Smith 2008). Like Raymond, Joseph had lived through traumatic experiences during the wars, and he wanted to know if socially and ecologically sustainable mining was possible and whether this activity might become a source of postwar peace and prosperity for people in his community. Joseph invited Raymond and me to his hometown and research site, and the three of us spent several months in various mining towns of Maniema province—especially the “company towns” of Punia, Kalima, and Kailo—together over three separate summers (we also visited Namoya and Kasongo). Joseph, Raymond, and I became close friends, and in whatever mining town we visited, our house became a perpetual seminar on artisanal mining and its impact, which drew in all kinds of people from all walks of life—men and women, young and old. However, we were the students, and our guests were the teachers. In the Kivus, Raymond and I spent several months, over multiple visits, in Walikale, North Kivu (a district with many small mines and one world-famous mine, Bisie), and took week-long visits from Goma to Nyabibwe in South Kivu over the years. We also made several visits of about a week at a time to the mining towns of Numbi, Walungu, Shabunda, and Luhwindja, in South Kivu, and Rubaya, in North Kivu, over multiple summers between 2011 and 2018.

In 2013, Raymond, Joseph, and I organized a conference on artisanal mining in Luhwindja, South Kivu, with funding from UC Davis and the NSF (Raymond chaired the conference). In Luhwindja, the Canadian company Banro was in the midst of a conflict with artisanal miners whom they were trying to expunge. Some diggers and representatives of Banro attended the conference, along with Congolese academics and a couple of academics from abroad. We invited researchers working on artisanal mining from the Catholic University of Bukavu, the official University of Bukavu, and NGOs to present papers. This was a high-octane interdisciplinary learning experience for me, as I got to learn a lot about different academic and nonacademic perspectives on mining in the setting of a contentious conflict between industrial and artisanal miners over “development,” the meanings and potencies of earth, and who had rights to the fruits of extraction. Some of the ideas that were generated during this conference also inform this book.

Slowly, as I grew to know more about eastern Congo and all that eastern Congolese had gone through, and as I came to more fully understand the nature and scope of the work that those involved in artisanal mining did and all of the powerful forces that were pitted against them, this project took on a different kind of urgency and weight for me. I came to see those in the trade as engaged in a recuperative project, as grappling—physically and conceptually—with some of the most profound issues and changes of our time and as pioneering new ways of engaging with and thinking through global capitalism while moving across ontological orders or dimensions (something discussed fully in chapter 3).

Probably the most intractable evidence of anthropology’s colonial legacy today is the assumption that anthropologists define their field sites, establishing what they’re going to do and who they’re going to do it with, as if they were completely in control of the social situation they just walked i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- part one: Orientations

- part two: Mining Worlds

- part three: The Eyes of the World on Bisie and the Game of Tags

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index