Learning Social Skills Virtually

Using Applied Improvisation to Enhance Teamwork, Creativity and Storytelling

- 104 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Learning Social Skills Virtually

Using Applied Improvisation to Enhance Teamwork, Creativity and Storytelling

About this book

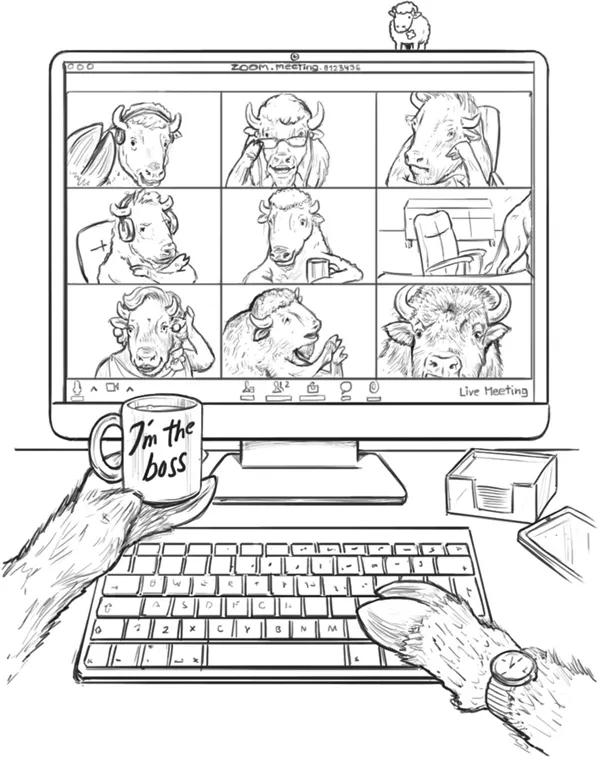

Digital workshops and meetings have established a firm foothold in our everyday lives and will continue to be part of the new professional normal, whether we like it or not. This book demonstrates how workshops and meetings held online can be made just as interactive, varied and enjoyable as face-to-face events.

The methods from improvisational theatre are surprisingly well suited for online use and bring the liveliness, playful levity and co-creativity that are often lacking in digital lessons and meetings. Applied improvisation is an experience-oriented method that is suitable for developing all soft skills – online and offline. Alongside brief introductions to the most relevant themes, the book contains numerous practical exercises in the areas of teamwork, co-creativity, storytelling, status and appearance, with examples of how to implement them online.

This book, written in the climate of the COVID-19 pandemic, is important reading for everyone – coaches, professionals and executives – looking for new impulses for their digital workshops and meetings, and who would like to expand the variety of their online methods. It offers new perspectives on many soft skills topics and supports interactive, engaging, lively and profitable online learning.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Applied improvisation

1.1 Origin of improvisational theatre

1.2 Introduction to applied improvisation

- attention and contact

- non-verbal communication

- co-creation

- spontaneity and intuition

- a culture of trust that allows for mistakes

- performance competence and presentation techniques

- communication

- creativity and innovation

- status and leadership skills

- storytelling

- team building

1.3 Basics of improvisation

Attention in the here and now

“Yes, and …” – accepting offers

Making your partner look good (“let your partner shine”)

1.4 Workshops with applied improvisation online

Technology

Interaction – camera and microphone on

- questions

- addressing participants directly

- exercises and role-playing games

- breakout sessions

Chat

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents Page

- Profiles Page

- Preface Page

- What you will find in this book Page

- 1 Applied improvisation

- 2 Creativity

- 3 Teamwork

- 4 Storytelling

- 5 Status and image

- 6 Practical examples

- Your takeaways from this book

- Literature

- Index