eBook - ePub

LOSING IT EB

About this book

'It's the kind of book that makes you wonder, 'why wasn't this written before?' It could change lives' EVENING STANDARD

'Turns everything you've been taught about sex on its head' RUBY RARE

What lies are we told when it comes to sex?

What impossible expectations pollute our health, our happiness and our access to fundamental human rights?

Bringing together deep research with intimate, real stories – from women who pay thousands for hymen reconstruction to men who fear their inexperience defines them – this is a revitalisation of sex education for the twenty-first century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Virginity Myth

‘Every time you have sex,’ I remember her saying, ‘you will lose your special glue. And when you have lost all of your special glue, no husband will love you.’

As part of the PSHE programme at my school, external speakers of varying quality would be invited in to talk to us about sex and drugs. This woman, with an Italian surname and over ten children, was one of them. No matter that there were girls in the year group who were gay, or who had already had sex. No matter that the school spent the rest of the time telling us to study hard so that we could get into top universities and careers. All that ambition and awareness dissolved in front of this woman’s formidable command of the room, because no husband was going to love us if we were special-glueless.

I wish I could tell you that her comments didn’t leave a mark on me. I know that they didn’t affect lots of the girls in the year, who sniggered, laughing her archaism off for what it was. Maybe it was because she was Catholic like me, with Italian family like me, that her words were imprinted firmly on my mind. All I know is that, in among the other sex education I had access to at school – free cinema tickets if we took chlamydia tests, and being given condoms – the Special Glue woman solidified the idea that sexual promiscuity was shameful, that my virginity was one of the most valuable things I possessed, and that my future sexuality was my husband’s, and not mine.

The Special Glue woman is an example of how much female virginity, and its inherent value, is an idea that still pervades our society. You don’t have to look at a not-even-that-religious school’s external speaker list to find this messaging; you can just search Twitter or Facebook posts, read the press or go to the cinema. Those of us who fangirled over Twilight absorbed the messaging that Bella Swan’s virginity is of value to Edward Cullen, who forbids sex until marriage. Virginity loss is transformative, turning her from a virginal, weak human into a sexed, powerful vampire, forever unable to return to her human form. You may have also listened to the song ‘Fifteen’ from Taylor Swift’s second album, in which she sings the lyrics: ‘Abigail gave everything she had / To a boy who changed his mind / And we both cried.’ You may now be observing the fractious midlife of popstar Britney Spears, whose virginity preservation was met with so much media fascination that the Church of England called her a role model. Or maybe you were still at school yourself when the Sun counted down the week leading up to Emma Watson’s and Charlotte Church’s sixteenth birthdays, eager to cash in on readers’ lascivious imaginings of the ‘barely legal’. How many of us can recall older men asking us if we were virgins or not, who wanted to hear us mutter ‘yes’? How many saw our sexual inexperience as relational to their sexual urges, irrespective of our own? This virginity obsession surrounds us, impeding what could be an easy, equitable journey into sexual maturity.

You might have grown up being told virginity was a ‘social construct’, or that it wasn’t a ‘real’ thing. But if you were, you grew up with enormous privilege. Many countries around the world still hold majority populations that condemn premarital sex, and women’s sexual freedom with it. Policing female sexuality and endorsing concepts like virginity usually go hand in hand, and even those of us who no longer have to bear the weight of this sort of performed sexlessness may still experience the vestigial consequences of an era that once punished us too. Modern sex educators now know to use other phrases about first-time sex – sexual debut or initiation – but many don’t understand the reasons why it is important to do so. Needless to say, even those of us who think we speak about first-time sex in an open-minded way are still probably quite close-minded about what the definition of virginity loss actually is, which is something we will unpack in more detail in Chapter 4. In limited curriculums that don’t have the time or funding to explain how power and gender affect our sex lives, there is often little room for addressing the virginity myth head-on – the idea that virginity still attributes value to women. It is a myth that went on to fill my own head with life-altering misinformation around sex, and that will undoubtedly have affected women in your life too. At its most mercenary and extreme, virginity’s value is economic, applied to porn stars, prospective brides, sex workers and trafficking victims. More commonly, it holds a spiritual and cultural value, portraying some women as worthier of a relationship, marriage, employment and even justice in a world that might promise sexual freedom, but still slut-shames.

All these values uphold the myth that our identity or status is transformed by first-time sex, as if we really do climb into that bed one person and out another. Not only is that ridiculous – were you a different person before you ate your first tomato, or wore your first pair of gloves? – but our sex lives shouldn’t define our access to acceptance, autonomy and justice.

You might think that at this point in the twenty-first century, the concept of virginity and its associated values might not really affect young women anymore. I get no pleasure in telling you that it very much does. For the past year I have received countless direct messages and anonymous posts from young women in the UK and abroad who have been led to believe that their first sexual experience could transform the outcome of their lives forever. This chapter, and the following two on the hymen and tightness, paint a portrait of a world in which the mythical status of female virginity continues to negatively affect women, and men, around the world.

*

In the Brazilian healthcare system, the Sistema Único de Saúde, Ana is entitled to three forty-minute psychiatry sessions a month for her bipolar disorder. Those sessions enable her, most of the time, to access some semblance of a normal, happy life. But lately, it’s been getting harder. Brazil has the second-highest death toll worldwide from the coronavirus pandemic, and her family is poor. She needed help to begin with, and now she needs more help. She hasn’t got any money, but she has something else that she thinks might be of value – her virginity.

‘Last night I realised something,’ she writes in an anonymous, now-deleted Reddit post. ‘Man [sic] pay a lot of money for a virgin girl. I have a beautiful body, not Instagram perfect but almost there. I never had sex.’ Reassuringly, she gets decent advice in the comments – namely that such an experience might make her mental health even worse. She replies to them quickly, and in one talks about her anxiety over the fact that ‘part of the virgin fetish involves making the girl bleed, the pain that she will feel. What if the man hurts me on purpose?’

Ana sounds like she’s encountered virginity porn, a niche within mainstream pornography. One of Pornhub’s most prolific channels in this area, the Defloration channel, has videos that rack up to 13 million views in which women are made to spread their legs and close-ups focus on what’s described as their hymens. The sex is then vigorous, forceful and, usually, involves the young woman screaming half with pain, half with pleasure. Go to free-to-view websites who don’t have to satisfy the conditions of credit card companies, and virgin porn fills with bloodlust. On XNXX, a ‘deflowering video’ shows a woman’s buttocks smeared with blood. Slightly further down, a penis is penetrating a woman whose vagina is emitting blood so viscous and red it looks like ketchup. Has Ana, curious about her body and what it means to men, seen these videos and felt their cold terror – long before she’s had a chance to understand what sex is really like, and what it should be?

I message her after I find this post, which at this point is a couple of months later. She tells me that she’s decided not to sell her virginity for three reasons. First, her Catholic faith condemns sex work and extramarital sex. Secondly, she told her mother, who cried and made her promise never to consider doing such a thing. And thirdly, her Reddit post opened up an alternative opportunity – making money through sending nudes. ‘After I posted that, a guy showed up in my inbox offering me money. I doubted but played along anyway to see what would happen. He offered me a lot of money for pictures and said I had to work out a way to receive money from another country. I made it clear that I would only send a photo after receiving the money. Of course, as I expected, it was a lie. After that he disappeared, but I want to find another man, one true to his word, to do the same thing: pics and talking in exchange of money.’

Ana’s story is but one in the virginity economy that continues to exist into the 2020s. Tales about online virginity auctions have featured in the British tabloid media for decades now; even suspect auction sites alleging to sell women’s virginities for millions claim column inches in media outlets such as the Daily Mail, who not only fail to do due diligence on them, but also fetishise the ‘proven’ virginities of such women, who have somehow obtained certificates from medical professionals. The articles, going by their comment sections, enjoy the novelty of clickbait popularity. There is no discussion of how virginity is a social construct, how these doctors are carrying out a human rights abuse, and how well these women are protected. Who cares, when virginity wins so many clicks, boosting the site’s ad revenue?

One woman I speak to, Lilly, sold her virginity online four years ago for €9,000 in Germany – enough for her to pay off her debt, but not remotely near the sums that the websites covered by the media suggest. When the requests started coming through, she had to ignore the vast majority because they didn’t want to wear a condom. In order to appear on the website’s auction platform in the first place, she was required to ‘interview’ with the owners, who got her drunk and forced her into sex games to make sure that she was ‘ready’. Once auctioned off, she had to give the website 15 per cent commission. Both she and the website profited from the economic value that her virginity held – but who really had the power here?

Virginity’s mythical value is one whose benefits are enjoyed by the powerful, not powerless. From certain brothels in Cambodia where virgin sex is considered to have anti-ageing properties, to Peru’s illegal gold mining region where it is believed by some miners that sex with a virgin will help you find gold, it is the sex traffickers who profit monetarily, and the male buyers who profit corporally. Our languages enshrine virginity’s role as a commodity; in English, virginity is lost or taken, for one-time use – a perishable good. There is the odd language that is different; in Swedish, virginity is dropped, as if you might be able to pick it back up again. But everywhere else, it seems forever gone; in Arabic you may not only lose it, you also might kasar it – break it. In Urdu, the verb for to lose that they use is not gomana, like if you lose a pencil; it is kohna, used if you lose something in an abyss or lose direction in life. Even our euphemisms in English for virginity loss – deflowering, popping or busting a cherry – denotes fruit or a flower that is ripe for the taking, and consumed without trace.

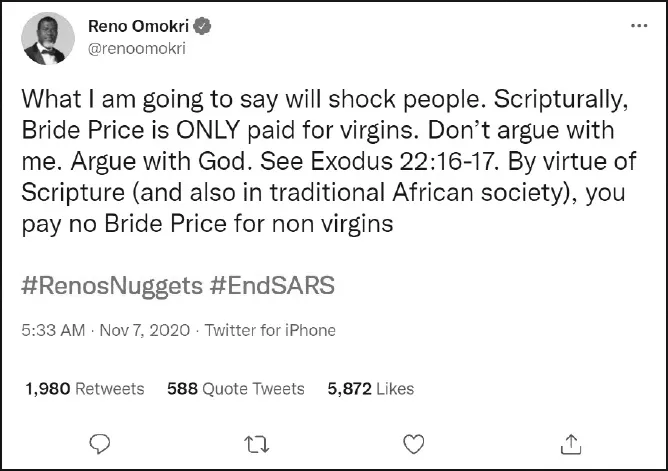

This value impacts women far beyond the world of sex work and trafficking. Bride prices, practised by millions of people, where grooms pay the bride’s family for the honour of marrying her, still alter in value depending on the bride’s virginity status in many countries and diasporas: ‘What I am going to say will shock people,’ tweeted Reno Omokri, a Nigerian former presidential aide, in November 2020. ‘Scripturally, Bride Price is ONLY paid for virgins. Don’t argue with me. Argue with God. See Exodus 22:16-17. By virtue of Scripture (and also in traditional African society), you pay no Bride Price for non-virgins.’

Why might a woman be of less bridely value if she isn’t a virgin? It’s not simply a matter of ‘purity’. A study in Ghana from 2018 might explain it a little; it found that male and female interviewees believed bride price was necessary for achieving desired masculinity and femininity in Ghana. The women saw it as bestowing respect and dignity in marriage, and men saw not paying a bride price as undermining their dominance in marriage. ‘Having a bride-priced wife was seen as a masculine accomplishment,’ writes the author. ‘We also found that paying the bride price meant there was an implicit moral obligation on a woman’s part to respect and obey her husband’s commands and wishes.’ A virginal bride, then, is a status symbol that represents a guarantee that a wife will be submissive.

On Twitter, Reno Omokri’s tweet received both support and criticism. But the majority of those who responded agreed with Omokri. Someone with 30,000 followers tweeted in reply: ‘if my to-be wife no be virgin, I dey reduce the bride price by 50 per cent [sad face emoji]’, to which a man with 16,000 followers responded, ‘I no go pay bro.’

Whether it’s on the internet, in a tabloid article or in gossip from neighbours, we are frequently reminded of how much more positively virginal women may be looked at than non-virginal, not only in conservative communities, but also in more liberal ones. Seven years ago, an eighteen-year-old on The Student Room said that they were thinking of breaking up with their girlfriend because: ‘I think the problem with her not being a virgin is that … I just can’t stop thinking about the fact that someone else has “spoilt” her.’

I, as well as several of my friends, can remember being told by men that they were happy they were our ‘firsts’, as if we had bestowed a great honour or gift on them, which had explicitly led to increased sexual enjoyment. Did they, too, think other women were somehow spoiled? These young men were not sexually illiberal themselves, so why the archaism? And – hauntingly – why were our virginities, either in our own performances of sexual inexperience, or simply their perceptions of it, part of our appeal well into the twenty-first century?

*

There was another, different response to Reno Omokri’s tweet, hidden among its many replies: ‘And what about men … if men have had premarital sex, what makes them worthy of marrying a virgin? … Did God give details about this too?’

It is safe to say that we all come from cultures in which religious ideology has influenced society. In secular countries, this influence does not simply disappear overnight, and for the 84 per cent of today’s global population who continue to follow a religion, influence is not disappearing but very much alive. While the world’s largest religions usually demand chastity for men and women, there is a catch; in lived practice, religious ideology is often responsible for demanding virginity more from women than of men. The double standards can be found in the figures who fill their sacred texts. Take orthodox Christianity, for example, in which sex is only acceptable within marriage and for the purpose of procreation. Both men and women are supposed to adhere to this doctrine; and yet, male virgins don’t seem to be fetishised for their virginal status, or have their sexual history engulf their identity. For female virgins, it happens as early as Genesis, where Rebecca is described to the wife-hunting Isaac as ‘very fair to look upon, a virgin, neither had any man known her’.

In Catholicism, female virginity is prized in the cult of the Virgin Mary, labelled by Simone de Beauvoir ‘the supreme victory of masculinity’ – perfect mother, perfect celestial bride and perfect virgin, all perfectly impossible mutual identities for actual women. The Catholic Church specifically insists in its doctrine that she remained perpetually virginal, long after Christ’s birth, and this subsumes her identity in a way that jars with how celibate men are referenced in Christian teaching. Although Jesus’ chastity is also celebrated, nobody says ‘the Virgin Jesus’. In Talmudic literature, virgins are entitled to increased alimony in the event of a divorce, which is double that of a widow’s; no similar privilege exists for male virgins. In Deuteronomy 22:17, a story is told of a man who wrongfully accuses his wife of having sex before marriage. Her bloodstained wedding-night sheet is shown to the elders of the town to exonerate her. In accordance with Jewish law, the man pays a fine to his wife’s father and is forced to remain married to her for the rest of his life. I’m sure that goes down well with the wrongfully slandered woman at the heart of this.

In Islam, the Hadith describes Muhammad asking a companion why he married a divorcee instead of a virgin with whom ‘he could sport’. The Qur’an also speaks of a paradise where good Muslim men will be able to enjoy maidens who are ‘chaste, restraining their glances, whom no man or jinn before them has touched’ [55:56]. Similar comments are not made about men. Meanwhile in Hinduism lie stories in which the heroines of Sanskrit epics have to walk through fire unscathed to prove their chastity, and legends like that of Draupadi, who walks through fire five times to become a virgin again for each of her five husbands. Across all the faiths, women’s virginity has mattered more than men’s.

As these religions grew and blended with culture and society, stories perpetuating these double standards continued. When Christianity blossomed in Europe, so too did the stories of female saints whose virginity played such a seismic role in their sainthoods that they are literally known as the Virgin Saints, cruelly martyred by pagan Romans who wanted to have sex with them but were rebuffed because they were ‘brides of Christ’. Christian literature documents over fifty of them and they are some of the faith’s most blood-soaked stories. Agatha in Sicily rejects the advances of the proconsul Quintiliano because she has promised her virginity to Christ in heaven. Quintiliano responds by imprisoning her in a brothel, torturing her and chopping off her breasts in fury. Women like Agatha became patron saints whose stories were taught in churches; they were heralded as heroines and used as examples of idealised female identity to young women. If Agatha can keep it in her pants in the face of Roman torture, then you can too.

But where are the male virgin saints? Heroic stories about them are few and far between. One exception is Sir Lancelot’s son, Galahad. In the Arthurian quest for the Holy Grail, the cup that Jesus was said to drink from during the Last Supper, it is only Galahad who can actually claim it because he is a virgin. It is more common for men to be born of virgins than to be remarked on for being virgins themselves; this includes Jesus Christ but also Alexander the Great and the twins Romulus and Remus. Romulus ended up killing his brother and sanctioning the rape of the Sabine women to boost Rome’s population; he didn’t need to be an innocent virgin to be remembered by history. To be a masculine hero, other qualities are demanded of you – often triumph and virility.

One may wish to be wary of accepting virginity’s place in a religious world when it is neither policed nor promoted in a gender-equal way and does more to perpetuate patriarchy than simply enable living out one’s faith. In 2014, Pew Research Centre’s Global Morality survey found that plenty of countries around the world still possess majority populations that disapprove of premarital sex – especially Muslim-majority countries. One of those countries is Indonesia, where 97 per cent of the population disapproves of it, and where the army has just announced that it has bowed to pressure from human rights groups to change its rules so that female soldiers no longer have to take virginity tests to join the army. Male soldiers have never had to take them. Another of these countries, Turkey, was forced to issue a decree in 2002 banning virginity testing after their health minister tried to bring in a rule that midwife and nursing students should be virgins. Again, male nurses were never expected to be subjected to these. But chastity was deemed a quality that would make these women better soldiers, better nurses and better midwives to such a degree that the highest legislators in their respective lands considered them.

So, what is the effect of growing up around the idea that you’re only worth as much as your sexual status, because your religion – the moral code you and your community cling to – told you so? The USA gives us a lot of insight. Blair, who grew up homeschooled in the US, was only able to truly take stock of her upbringing in her twenties when she finally sought the help of a sex educator. She grew up in a Southern Baptist community, where she was taught things like ‘sex before marriage is a sin that grieves the heart of God’ or that it was ‘the sin next to murder’. Blair can remember times when the boys would be told to go outside and play sports and the girls would be kept in and taught about virtue and securing a future husband. ‘We were responsible for keeping ourselves in check and not being too flirtatious or dressing even slightly immodestly because guys are more visual. Guys can’t control their thoughts.’

Blair went to these lessons for the duration of her high school years, and contin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. The Virginity Myth

- 2. The Hymen Myth

- 3. The Tightness Myth

- 4. The Penetration Myth

- 5. The Virility Myth

- 6. The Sexlessness Myth

- 7. The Consent Myth

- 8. The Future Story of Sex

- Conclusion: Nothing to Lose

- Selected Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access LOSING IT EB by Sophia Smith Galer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Human Sexuality in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.