- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

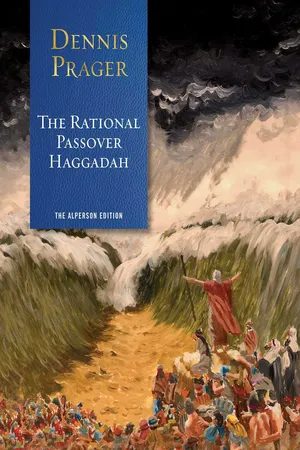

The Rational Passover Haggadah

About this book

Dennis Prager, author of The Rational Bible —which, upon its first publication, was the number one bestselling non-fiction book in America—turns his attention to the Haggadah, the book used for the most widely celebrated Jewish ritual, the Passover Seder. As with Prager's multi-volume commentary on the Torah, the explanations included with this Haggadah are equally valuable for religious and non-religious Jews, as well as for non-Jews. It provides enough thought-provoking ideas and insights to last the reader a lifetime.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Rational Passover Haggadah by Dennis Prager in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Jewish Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Passover Seder and the Haggadah

Given that the Passover Seder is the most widely observed Jewish ritual, most Jews—and an increasingly large number of non-Jews—are familiar with the Hebrew word “seder.” However, few people know what the word means: it is the Hebrew word for “order.” The modern Hebrew word for “OK”—b’seder—literally means “in order.”

The name “order” was given to the Passover ritual meal because it is conducted in a set order. The Seder consists of fifteen steps written down in a book called the Haggadah (Hebrew for the “telling,” because it tells the story of the Exodus from Egypt). Understand these steps and you will understand what the Rabbis wanted to achieve at the Passover Seder. “Rabbis” refers to the ancient rabbis who compiled the Talmud, the holiest Jewish work after the Hebrew Bible. The Talmud, finalized in about the year 500, is the size of a large encyclopedia. It is comprised of dozens of volumes containing philosophy, theology, legends, stories, and, most of all, arguments and discussions about how to carry out Jewish laws. The earliest date for the Haggadah is 170, but the finalized edition dates to approximately 750.

Why does the Haggadah exist? Because the Torah, the first five books of the Bible, commands Jews to tell the story of the Exodus during the holiday of Passover (see Exodus 13:8 and 13:14–15), but it does not specify how to do so. Post-biblical Jewish law did.

Were it not for the Seder and Haggadah, a person would fulfill the Torah commandment in any way he or she chose. Perhaps there would be a holiday meal with family and/or friends at which some people might discuss the Exodus; perhaps a rabbi or a group of Jewish laymen would discuss the Exodus at synagogue; or perhaps one would talk about the Exodus in a phone call with a friend or relative. All of these would theoretically fulfill the Torah law, but none would come close to being a Seder.

In addition, any Jew can fully celebrate the Seder with other Jews anywhere in the world. All Jews recite the same Haggadah and therefore have the same Seder.

Finally, while there is plenty of room for spontaneous discussion—as we will see, it is encouraged—the authors of the Haggadah wanted to ensure that Jews incorporate certain aspects of the Exodus story and the Passover holiday at the Seder.

It has worked well. Though Jews were exiled from their homeland for nearly 1,900 years, they not only retained their national identity—a unique achievement in human history for a dispersed people—they also kept the story of their Exodus from Egypt alive. The Passover Haggadah and the Seder are what made that possible.

For Discussion What Is More Important in Judaism—the Home or the Synagogue?

The central religious institution in Jewish life is not the synagogue. The synagogue, where Jews gather for communal prayer, is certainly important, but the central religious institution in Judaism is the home. The synagogue is essentially a religious adjunct to the home. The home is where the holidays—most important, the weekly Shabbat (Sabbath)—are celebrated. While many synagogues today conduct a Seder, the vast majority of Jews throughout Jewish history have observed the Seder in a home—either their own or that of a relative or friend.

That is why virtually no Jew celebrates the Seder alone. If Jews learn that some Jew has no home to go to for the Seder, it is likely he or she will be invited to someone’s Seder. Within the context of Judaism, a Jew being alone on Seder night is particularly sad. After all, the purpose of the Seder and the Haggadah is to tell a story, and one needs others to whom to tell the story. Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) are the most important Jewish holidays (along with Shabbat)—hence they are referred to as the “High Holy Days”—and most Jews will have at least one High Holiday meal with other Jews. But it is the Seder meal that most Jews feel the greatest need to share with others.

Therefore, Jews should seriously consider inviting one or more individuals other than family and close friends to their Seder. There are undoubtedly Jews in your city who, for whatever reason, do not have family or friends with whom they are celebrating the Seder. No Jew should be alone on this night. At the same time, I also suggest inviting non-Jews to your Seder. For too long, Judaism has been hidden from the world. This has not done the Jews or the world any good.

THE SEDER

The Seder begins with the reading or chanting aloud of its fifteen steps—somewhat like starting a nonfiction book by reading aloud the chapter titles.

The Fifteen Steps of the Seder

1. Kadesh: Kadesh means “sanctify” or “consecrate.” We begin the Seder by reciting a prayer of sanctification over wine.

2. Urchatz: A ritual washing of the hands. This is an act of purification, not a cleaning of the hands. Our hands are expected to already be clean before the ritual washing. The washing is a statement that one is about to engage in a holy act.

3. Karpas: We eat a vegetable such as parsley, celery, or potato (but not a bitter herb). This reminds those at the Seder that Passover falls in the spring, a time of rebirth and renewal.1 Indeed, the Torah describes Passover as chag he-aviv, “the spring festival.”

4. Yachatz: The word means “cut in half.” There are three matzot (pieces of matzah, the unleavened bread of Passover) on the Seder leader’s (and sometimes on other participants’) plate. The leader (and any other participant who wishes) breaks the middle matzah in half. The larger of the two pieces is then set aside to be consumed as the final item eaten at the Seder.

5. Magid: The word means “tell.” It is the same word as the root of the word Haggadah, “the telling”—of the story of the Exodus. This is the longest and most important part of the Seder. Telling the story is the purpose of the Haggadah and, for that matter, of Passover.

Nations that do not tell their story to each succeeding generation will eventually have no succeeding generation to whom to tell their story. More on this in the Magid section.

6. Rachtzah: This is the second washing of the hands (rachtzah is from the same word as urchatz). The first, which had no accompanying blessing, is unique to the Passover Seder. This second washing is accompanied by a blessing—the same blessing recited before all other meals in Judaism.

7. Motzi: The word means “brings forth,” the Hebrew word contained in the traditional blessing recited when eating bread: Baruch ata Adonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, ha-motzi lechem min ha-aretz (Blessed are You, Lord, King of the universe, Who brings forth bread from the earth). The reason the blessing over bread is recited is that matzah is bread, but it is unleavened bread.

8. Matzah: This is the unique blessing for the first eating of matzah on Passover. Eating matzah on Passover is so important that the Torah refers to Passover as Chag HaMatzot, the “Holiday of Matzot.”

9. Maror: The word means “bitter.” This is the bitter herb (raw horseradish is commonly used), eaten to remind us of the bitterness of slavery.

10. Korech: This alludes to a “sandwich” that combines the bitter herb and the sweet haroset (a paste usually comprised of apples, nuts, and cinnamon among other ingredients) between pieces of matzah.

11. Shulchan Orech: The words literally mean “Set Table,” and signify the luxuriant Passover meal.

12. Tzafun: The word means “hidden.” The meal ends with the eating of the hidden matzah which was broken at the beginning of the Seder. This piece of matzah—about which more will be said later—is known as the afikoman, derived from the Greek word for dessert. Subsequent to the afikoman, the Jewish practice is not to eat anything, with the exception of drinking the third and fourth cups of wine (or grape juice, if a substitute for wine is necessary—see pages 10–11 for an explanation of the four cups of wine). Considering how delicious the meal and the desserts were, the afikoman is admittedly a letdown. However, the Rabbis were more interested in meaning than in cuisine.

13. Barech: The word means “bless” and refers to the Birkat HaMazon, the Grace after Meals, a series of prayers thanking God for the food and much else.

14. Hallel: The word means “praise” and is the root of the well-known Hebrew word “Hallelujah.” Some psalms from the Book of Psalms are recited.

15. Nirtzah: The word means “acceptance.” This is the Seder’s completion, when we pray that “just as we were able to carry out the Seder’s order this year, so may we be able to carry it out again.”

For Discussion Why Are Rituals Important, Even Vital?

As noted in the introduction, Jews have celebrated Passover for thousands of years. It is most likely the longest-observed ritual in the world, a testament to the power of ritual to perpetuate gratitude and national identity, both of which rely on memory.

Memory, in turn, relies on ritual. Human beings find perpetuating gratitude very difficult. Unless people make a deliberate effort, the good that another has done for them is usually forgotten quickly. Remembering hurtful things comes far more naturally to people than remembering the good things done to them. That Jews have been grateful to God for the Exodus for over three thousand years is solely due to their observance of Passover, which is all the more remarkable in light of all the terrible suffering Jews have since experienced.

The need for ritual is just as true in secular life. Using America as an example, the holidays with the most observed rituals—Thanksgiving and Christmas—remain widely observed. On the other hand, holidays during which few or no rituals are observed—Presidents’ Day, for example—remain on the calendar, but are observed only as vacation days and are essentially devoid of meaning.

There is also a proof within Jewish life of the need for ritual. The reason Passover is the best-known and most widely celebrated of the three festivals is thanks to its Passover Seder ritual. The next best-known Torah festival (though not nearly as widely celebrated) is Sukkot (tabernacles), also because of its rituals of building a sukkah (booth) for the holiday (see Deuteronomy 16:13–15), gathering with friends and family in the sukkah for meals, and daily blessings over a lulav (palm frond) and etrog (citron), along with myrtle and willow. The least well-known of the three festivals among Jews is Shavuot (Pentecost)—precisely because it is essentially devoid of specific rituals (though many Jews engage in the ritual of studying the Torah much of, or even the entire, night).

A post-Torah holiday, Chanukah, commemorating an event that occurred about 1,100 years after the Exodus, is widely observed precisely because of the ritual of lighting an additional candle each night of the holiday’s eight days. Chanukah would not be nearly as widely observed if not for the holiday’s candle-lighting ritual (and, in the West, because of its proximity to Christmas).

קדש KADESH (The Kiddush)

In keeping with the central theme of the holiday, the Passover Kiddush—the blessing over the wine—speaks of “the feast of Matzot, the season of our freedom… in memory of the Exodus from Egypt.”

The blessing over the wine itself—Blessed are You, Lord our God, Who has created the fruit of the vine—is but one sentence, placed between the two large paragraphs of the Kiddush.

Another one-sentence blessing is appended at the end of the Kiddush: Blessed are You… Who has kept us alive, sustained us, and brought us to this time. This blessing, known as the shehecheyanu, is said on holidays and other happy occasions. It is intended to ensure that people express gratitude for the good things—even minor good things—in their lives. It is, therefore, not only recited at the start of Jewish holidays, but when tasting a fruit for the first time in any given season, when putting on new clothes, or when moving into a new house.

Regarding the joyousness of the holiday, there are actually laws in the Torah that command the Jew “to be happy” on the festivals—specifically Shavuot and Sukkot (Deuteronomy 16:11, 13–16). Interestingly, the Torah does not command happiness on the third of the three festivals, Passover. On Passover, the Torah assumes the believing Jew will be happy, given that the holiday is about escaping slavery. The emotion the Torah and later Judaism seek to evoke on Passover is gratitude (which, as it happens, is the primary creator of happiness). In effect, the gratitude inculcated by Passover makes the happiness of the other two festivals possible.

The Torah’s command that the Jew be happy is what shaped my understanding of happiness—that it is both a choice and a moral obligation. Most people think happiness is a feeling or emotion that one either has or doesn’t have at any given moment. Judaism made me realize that happiness is largely a choice. As the American president Abraham Lincoln, who suffered terrible emotional pain throughout his life, put it, “People are about as happy as they make up their minds to be.”

So even if you are in a bad mood as Passover begins—or, for that matter, at any time in life—you owe it to all those around you to act as happy as you can (or, at the very least, not to inflict your bad mood on them). That is another significant insight Judaism has contributed: feelings should not dictate behavior, and behavior shapes feelings.

Pour the first cup. The matzahs remain covered. The Kiddush (“Sanctification”) over the wine is usually recited by the leader of the Seder. At many Seders, others recite the Kiddush after the leader does. Lift the cup and recite/sing the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- 1. The Passover Seder and the Haggadah

- 2. The Seder

- 3. Kadesh (The Kiddush)

- 4. Urchatz (And Wash)

- 5. Karpas (Greens)

- 6. Yachatz (Break the ‘Afikoman’ in Half)

- 7. Magid (Telling—the Exodus Story)

- 8. Answering the Four Questions: The Narrative of the Haggadah

- 9. God, Not Moses, Is Credited with the Exodus

- 10. Even Scholars and the Most Wise Must Retell the Story of the Exodus on This Night

- 11. The Four Sons

- 12. The Jews Began as Primitive as All Other Peoples

- 13. In Every Generation, Someone Seeks to Annihilate the Jews

- 14. God Alone—No Angel, No Human—Killed the Firstborn

- 15. The Ten Plagues

- 16. Dayenu: The Song of Gratitude

- 17. The Passover Sacrifice, ‘Matzah’, and ‘Maror’

- 18. Hallel (Psalms Part I)

- 19. The Second Cup of Wine

- 20. Rachtzah: Washing

- 21. Motzi Matzah: Taking Out the ‘Matzah’

- 22. ‘Maror’: Bitter Herbs

- 23. Korech: Sandwich

- 24. Shulchan Orech (The Set Table): The Seder Meal

- 25. Tzafun: The Concealed (‘Matzah’)

- 26. Barech (Blessing over the Food): Birkat HaMazon

- 27. The Third Cup of Wine

- 28. Hallel (Psalms Part II)

- 29. Songs of Praise and Thanks

- 30. The Fourth Cup of Wine

- 31. Nirtzah: Acceptance and Conclusion

- 32. The Four Last Songs

- 33. The Principles of the Jewish Faith

- Notes

- Selected Essays from ‘The Rational Bible: Exodus’

- Copyright