eBook - ePub

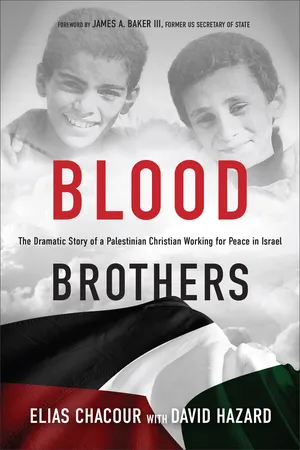

Blood Brothers

The Dramatic Story of a Palestinian Christian Working for Peace in Israel

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Blood Brothers

The Dramatic Story of a Palestinian Christian Working for Peace in Israel

About this book

As a child, Elias Chacour lived in a small Palestinian village in Galilee. When tens of thousands of Palestinians were killed and nearly one million forced into refugee camps in 1948, Elias began a long struggle with how to respond. In Blood Brothers, he blends his riveting life story with historical research to reveal a little-known side of the Arab-Israeli conflict, exploring whether bitter enemies can ever be reconciled. This book offers hope and insight to help each of us learn to live at peace in a world of tension and terror.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Blood Brothers by Elias Chacour,David Hazard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

News in the Wind

Surely my older brother was confused. I could hardly believe what he was telling me. I leaned dangerously far out on a branch, my bare feet braced against the tree trunk, and accidentally knocked a scattering of figs down onto the head of poor Atallah who had just delivered the curious news.

“A celebration?” I shouted from my tilting perch. “Why are we having a celebration? Who told you?”

“I heard Mother say,” he called back, dodging the falling figs, “that something very big is happening in the village. And”—he paused, his voice sinking to a conspiratorial hush—“Father is going to buy a lamb.”

A lamb! Then it must be a special occasion. But why? It was still a few weeks until the Easter season, I puzzled, sitting upright on the branch. At Easter-time our family celebrated with a rare treat of roasted lamb—and for that matter it was one of the few times during the year that we ate meat at all. We knew—because Father always reminded us—that the lamb represented Jesus, the Lamb of God. And, of course, I realized that Father was not going to buy a lamb. We rarely bought anything. We bartered for items that we could not grow in the earth or make or raise ourselves, the same as everyone else in our village of Biram.

I’m sure Atallah knew that if he waited around, he was risking another barrage of figs and questions. He was already trotting away toward the garden plot beyond our small stone house where I should have been helping Mother and the rest to clear away rocks. It was an endless job even then, in 1947, since no one in our village of Biram owned farm machinery to make work easier. When school had ended an hour before, I had hidden up in this fig tree—my tree, as I called it—to escape the labor. Now, watching Atallah disappear, I wondered what exciting event was rippling the too-regular course of our lives.

I must find Father and ask him myself, I decided.

Instead of dropping down into the deep orchard grass to trail after Atallah, I shinnied higher up the fig tree—up to the very top, where the branches bent at dangerous angles under my weight. This was my special place. Besides being a good lookout post, it bore not one, but six different kinds of figs. My father, who was something of a wizard with fruit-bearing trees, had performed a natural magic called grafting and combined the boughs of five other fig trees onto the trunk of a sixth. A thick, curling vine trellised up the trunk and spread through the branches, too, draping the tree with clusters of mouth-puckering grapes. Many afternoons, I monkeyed my way up onto a high branch, sampling the juicy fruit until my stomach cramped. Then I would ease down into Mother’s cradling arms and she would comfort me, her littlest boy—her dark-haired, spoiled one.

“Elias,” she would coo over me, shaking her head. “You’ll never learn, will you?” And I would bury my face in her thick hair, groaning as my four older brothers and my sister rolled their eyes in disgust.

Now, with one arm crooked around the topmost branch, I pushed aside the curled leaves, thrusting my head out into the spring sun, which was slanting toward late afternoon. Perhaps Father was in his orchard. Row after row of fig trees spread for several acres, stretching down the hill away from our house, covering the slope with rustling greenery. The broadening leaves concealed a freshwater spring and a dark, mossy grotto where our goats and cattle sheltered themselves in summer. Beyond our orchards rose the lush majestic highlands of the upper Galilee. They looked purple in the distance—“the most beautiful land in all of Palestine,” Father said so often. A dreamy look would mist into his pale blue eyes then, as it did whenever he spoke about his beloved land.

Search as I might, I could not find Father ambling among those trees just now. Most days he worked there with my brothers, teaching them the secrets of husbandry. At seven years old, I was considered too young—and too impish—to learn about the fig trees. With or without me, my father and brothers had busheled up three tons of golden-brown figs in the last harvest.

With a recklessness that would have paled my mother, I swung down from the treetop and flung myself to the ground. Then I was off, running toward the center of the village. Surely someone had seen Father.

I darted through the narrow streets—hardly streets at all, but foot-worn, dirt corridors that threaded the homes of the village together beneath the shade of cedar and silver-green olive trees—dodging a goat and some chickens in my path. Biram seemed like one huge house to me. Our family, the Chacours, had led their flocks to these, the highest hills of Galilee, many hundreds of years ago. My grandparents had always lived here, nearly next door to us. And there were so many aunts, uncles, cousins and distant relatives clustered here, it was as if each stone dwelling was merely another room where another bit of my family lived. All the homes fit snugly together right up to our own, the last house at the far edge of the village. Biram had grown here, quietly rearing its children, reaping its harvests, dozing beneath the Mediterranean stars for so many generations that all households were as one family.

And today this whole family seemed to be keeping a secret from me. I ran from house to house where small knots of kerchiefed women in long, dark skirts were talking with hushed excitement. Eagerly, I burst in on a group of older women, some of my many “grandmothers.” They stopped clucking at each other only long enough to shush me and shoo me out the door again.

My feelings bruised, I trotted toward our church, which was the living heart of Biram. Here the entire village crowded in on Sundays, shoulder to shoulder beneath its embracing stone arches. The parish house, a small stone building huddled next to the church, doubled as a schoolhouse during the week, its ancient foundations quaking from our noisy activities. This year was my first in school, and I loved it. Now, in the church’s moss-carpeted courtyard, a group of men were talking loudly. Father was not among them, so I bounded off toward the open square just beyond.

Normally I hesitated before entering the square. This was the realm of men—especially the village elders—and it held a certain awe for me. Children were tolerated here only because we were plentiful as raindrops and just as unstoppable. However, we knew enough to keep a respectful margin between our foolish games and the clusters of men who came in the evening to hear news that the traveling merchants carried in from far-off villages along with their shiny pots, metal knives, shoes and what-not. Tottering at the edge of the square were the stony, skeletal remains of an ancient synagogue. On this spot, Father had told us, the Roman Legions had built a pagan temple many centuries ago. The Jews later destroyed the temple and raised on its foundations a place of worship for the one, true God. Now the synagogue stood ruined and ghost-like, too. It was forbidden to play among the fallen pillars, and any child brazen enough to do so suffered swift and severe punishment, for it was considered consecrated ground.

That day I shot out into the sun-bright square—and nearly toppled to a halt. The square, it startled me to see, was not abandoned to the clots of older men who usually nodded there in the afternoon warmth. Men young and old were huddled everywhere, talking about . . . what? Surely everyone had heard the news but me!

Impatiently, my dark eyes scanned the groups of men for Father’s slender form. It was no use. Nearly all the men wore kafiyehs, the white, sheet-like headcoverings that shaded their heads from the Galilean sun and braced them from the wind. At a glance, almost any of them might be Father!

On tiptoe I carefully laced my way between these huddles, peering around elbows in search of that one lean, gentle face. The faces I saw looked pinched and serious. Whatever they were discussing was most urgent. Otherwise they would not be gathered here on a spring afternoon when fields wanted plowing and trees awaited the clean slice of the pruning hook.

Not that I was eavesdropping, of course, but amid the murmur of discussion I picked up the fact that Biram was expecting a special visit. But who was coming? Visits by the bishop were quite an event, but regular enough that they did not cause this kind of stir.

My sneaking was not altogether unnoticed, however. Poking my face into one circle of men, I stared up into a pair of black, deep-set eyes belonging to one of the two mukhtars of Biram—a chief elder in the village. I tried to duck, but—“What do you want here, Elias?” The mukhtar’s voice was gravelly with an edge of sternness.

My face reddened. Would I ever learn not to barge into things?

“I . . . uh . . . have you seen my father? I have to find him—it’s important.” I hoped that I sounded convincing, and it was true enough since I was about to die with curiosity.

The sternness of his look eased a bit. “No, Elias, I haven’t seen him. He’s probably—”

“I spoke with him earlier,” another man interrupted. “He went trading today—I don’t know where. Maybe over in the Jewish village.” Then he stepped in front of me, closing the circle again. Thankfully, I was forgotten.

The Jewish village? Perhaps. As I fled from the square, I remembered that Father often went there to barter. Many of these Jewish neighbors came to Biram to trade as well. When they stopped by our house for figs, Father welcomed them with the customary hospitality and a cup of tar-like, bittersweet coffee—the cup of friendship. One man was a perfect marvel to me, roaring into our yard almost weekly in a sleek, black automobile—the first one I had ever seen.

At the far edge of town, I stopped, craning my neck to look far down the road. It was empty. If Father was on his way to the Jewish village, he was long gone.

My eagerness fizzled. And still I could not take my eyes off the road, hoping for some glimpse of him. Beyond the next hill, the road wound southward to Gish, our nearest neighboring village. And further down the valley, not many kilometers, the Mount of Beatitudes rose up from the Sea of Galilee’s northern shore. I could not see the Mount from where I stood and had never seen it for that matter, for even a few kilometers seemed a long journey from our mountain fastness.

Past the Sea of Galilee I knew almost nothing. I could not imagine the unreal world beyond—a world that Father said had just warred against itself. I could not fathom such a thing. Mine was a peaceful world of fig and olive groves, countless cousins, aunts and uncles. Time passed almost seamlessly from one harvest to another, marked only by births, deaths and holidays. I felt safe and sheltered here, as if the very arms of God embraced our hills like the strong, overarching stones of our church.

Certainly, this was a childlike vision. Only vaguely was I aware of distant disturbances.

There had been trouble in the mid-1930s, before my birth. Father told us there had been opposition to the British who had driven out the Turks and now protected us under a temporary mandate. Strikes and riots had shaken Jerusalem, Haifa and all of Palestine, but these were quickly quelled. It was just one more incident in the long history of armies that traversed or occupied our land. Then things had settled, so it appeared, into a lull. Soon, it was hoped, the British would establish a free Palestinian government, as they had promised. Without a single radio or newspaper in all Biram—even then, in the late 1940s—we had no inkling that a master plan was already afoot, or that powerful forces in Jerusalem, in continental Europe, in Britain and America were sealing the fate of our small village and all Palestinian people.

As I stood dejectedly on the road from Biram, with the sun settling low and red on the hills, my only thoughts were of Father. And Mother . . . oh no! I had forgotten about Mother! Surely she would be home from the fields, upset to find that I’d wandered off again. My feet were flying before I’d finished the thought.

At the edge of our orchard, the sweet scent of woodsmoke from Mother’s outdoor fire met me, and the steamy sweetness of baking bread. Mother was stooping over her metal oven, which stood on a low grate next to the house. My sister, Wardi, fed sticks to the licking flames, and on the grate, a pot of tangy stuffed grape leaves boiled. My brothers were hauling wood and water. If only I could slip in quietly among them, Mother might not realize I’d been away . . . But Atallah spotted me first. Nearest to me in age, he was my best ally—and sometimes my dearest opponent.

A tell-all sort of smirk lit his face, and he announced in a clarion voice, “Mother, here’s Elias now.”

Mother looked up at me, the firelight playing about her pleasant, full face. A brightly colored kerchief drew her hair up in a bun. I cringed, expecting a sound scolding. At that moment, however, she seemed unusually distracted, her gentle eyes clouded in thought. “Go and help Musah carry the water,” she murmured, waving me away.

Musah, who was the next oldest after Atallah, was beside me in an instant. He thrust an empty bucket at me. “Get busy,” he ordered with a triumphant grin.

I had to know before I exploded. “Mother, what’s happening in Biram? Is Father buying a lamb? Is it a celebration?”

“Take the bucket,” Musah demanded, his grin fading.

“Mother, tell me. Everyone knows but me and—”

“A celebration? Well, yes. Perhaps. Father wants to tell you himself. I said go help your brother.”

“Take the bucket,” said Musah, thumping me with it.

“Mother,” I stomped impatiently. At that moment, a familiar voice called to me through the trees.

“Hello, Elias. I’m glad to see such a happy helper.” From the shadowy green darkness beneath the fig boughs, a lean figure stepped out into the circle of firelight. Behind him, led by a short cord of rope, was a yearling lamb.

Father was home!

When Father returned home at the end of each day, he brought with him a certain, almost mystical calm. His eyes lit up in the flicker of firelight, and a placid smile always turned up the corners of his thick mustache. At his appearance, disputes between children ceased instantly. For one thing, Father was stern with his discipline. Play was one matter, but rude behavior did not befit the children of Michael Chacour. More than that, I believe we all felt the calm that seemed to lift Father above the squabbles of home or village. Above all, Father was a man of peace.

I raced to catch his hand, absolutely dying to ask a million questions. The weary slump of his shoulders made me think better of it. Father was no longer a young man; in fact, he was almost fifty. His light brown hair and mustache were tinged with silver-gray. For once I held my tongue, and instead, quietly stroked the lamb’s dusty-white face.

Turning to Mother, he smiled. “Katoub, has the Lord sent us anything to feed these hungry children?”

Mother knew, without Father’s gentle hints, that he, too, was hungry and footsore. “Come, children—quickly,” she said, sparking into action. She waved Musah off to the stable on the far side of the house to pen the lamb. Then she mustered the rest of us into a circle around the fire. It was our daily drill: children were organized and quieted, for evenings belonged to Father.

If some important news was in the wind, Father did not seem ruffled by it in the least. No matter that I was about to split in half with curiosity! He accepted a steaming plate of food from Mother, settling with a regal quietness beside the sputtering fire.

Just when I was certain I would explode, Father set aside his plate. “Come here, children. I have something special to tell you,” he said, motioning for us to sit by him. It had grown fully dark and chilly, and I pressed in close at his side.

“In Europe,” he began, and I noticed a sadness in his eyes, “there was a man called Hitler. A Satan. For a long time he was killing Jewish people. Men and women, grandparents—even boys and girls like you. He killed them just because they were Jews. For no other reason.”

I was not prepared for such horrifying words. Someone killing Jews? The thought chilled me, made my stomach uneasy.

“Now this Hitler is dead,” Father continued. “But our Jewish brothers have been badly hurt and frightened. They can’t go back to their homes in Europe, and they have not been welcomed by the rest of the world. So they are coming here to look for a home.

“In a few days, children,” he said, watching our faces, “Jewish soldiers will be traveling through Biram. They are called Zionists. A few will stay in each home, and some will stay right here with us for a few days—maybe a week. Then they will move on. They have machine guns, but they don’t kill. You have no r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Epigraph

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- An Urgent Word Before

- 1. News in the Wind

- 2. Treasures of the Heart

- 3. Swept Away

- 4. Singled Out

- 5. The Bread of Orphans

- 6. The Narrowing Way

- 7. The Outcasts

- 8. Seeds of Hope

- 9. Grafted In

- 10. Tough Miracles

- 11. Bridges or Walls?

- 12. “Work, for the Night Is Coming”

- 13. One Link

- Epilogue

- Afterword

- Abuna Elias Chacour’s Ministry Today

- Notes

- Back Cover