- 343 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Renaissance and Reformation

About this book

Readable and informative, this major text in Reformation history is a detailed exploration of the many facets of the Reformation, especially its relationship to the Renaissance. Estep pays particular attention to key individuals of the period, including Wycliffe, Huss, Erasmus, Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin. Illustrated with maps and pictures.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter I |  |

A MEDIEVAL MONTAGE

Very few periods in history are clearly fixed and agreed upon. For every position taken by a historian on the basis of the most solid evidence, there are opposing opinions. This is especially true in regard to the Middle Ages. Both nomenclature and dating are matters in dispute. The slice of history often designated “medieval” has been dated from 500 to 1500 and any number of other dates in between. The bracketing dates selected depend more upon the nature of the era in the eyes of the historian than the pegs upon which the historical narrative is hung. The crowning of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day in 800 A.D. marks a fairly definite turning point in the history of European civilization. But when the Middle Ages end and a new period begins is not so readily determined.

The term “Middle Ages,” although not without ambiguity, does have the merit of objectivity. Other terms often applied to the era, such as “the Age of Faith” and “the Dark Ages,” are more descriptive but hardly objective. Perhaps no one term, however appropriate, can provide an adequate umbrella for such a huge block of history—hence the logic of dividing the period into the Low Middle Ages and the High Middle Ages. In this case the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 provides a natural division. It certainly represents the medieval papacy at the apex of its power under the pontificate of Innocent III.

The intent of this chapter is to develop a picture of medieval Europe before the Renaissance had begun to gain enough momentum to make its impact upon the age. It will take a bit of imagination on the part of the reader to project himself or herself back into an age beginning some twelve centuries ago. But there is no possibility of understanding the revolutionary changes brought about by the Renaissance and Reformation movements without the effort.

FEUDAL EUROPE

The Middle Ages have been described as “a thousand years without bath.” While this statement, like most generalizations, is not wholly true, it correctly suggests that Europe, by modern standards, was filthy. This was certainly true of the peasants and of peasant life in general. A walk down a village street was an experience to forget. Every thatch roofed stone house was graced by its manure pile and stack of firewood. The stench was stifling and varied, dependent upon the predominant odor, the season of the year, and the time of day. Cows and goats—even hogs—frequently lived under the same roof with the peasant family. In a region where the winters were harsh and people were often snowbound for weeks on end, such an arrangement was both necessary and convenient, if somewhat unsanitary. And in an era when all of life was marked by pungent odors, what difference did it make?

But it did make a difference. Because of the lack of sanitation and ventilation typical of the hovels in which whole families frequently shared the same bed of straw, epidemics were frequent, and the infant mortality rate was high. Feeding on such conditions, the Black Plague, the scourge of Europe (which apparently originated in central Asia in about 1338), raced across Europe unchecked. It is estimated that thirty to forty percent of the population in the cities died as a result. And the death toll would have been far greater if more of Europe’s populace had lived in towns and cities. As it was, the plague returned with frightening regularity as Europe became increasingly overpopulated toward the end of the era. It is not difficult to understand medieval man’s preoccupation with the brevity of life and the certainty of death considering what he faced: famine, the recurring plague, and incessant warfare.

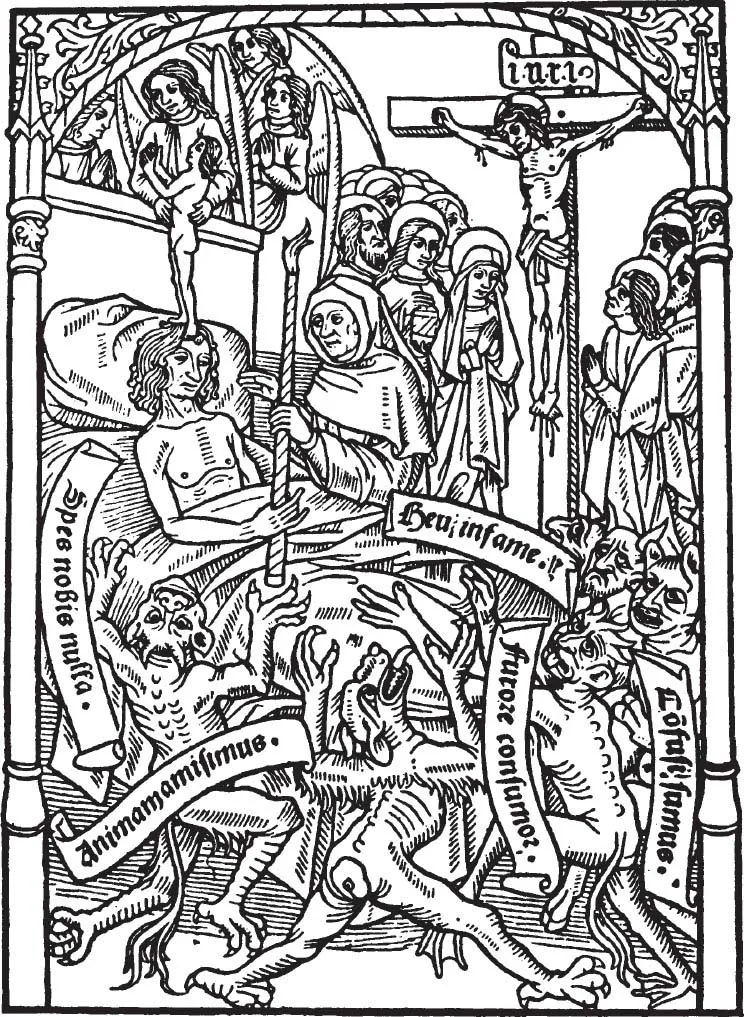

Artists reminded their contemporaries of the inevitable with their gruesomely detailed portrayals of the dance of death and scenes of the last judgment. It is little wonder that peasants lived in a state of perpetual fear and that their only hope lay in the church and its sacraments, of which the priest was the indispensable agent. Their superstitiousness and illiteracy increased both their burden and their dependence upon the church.

Page from The Art of Dying, which illustrates the fears of the medieval man

Medieval Europe was, for the most part, an agrarian society. With Charlemagne’s empire broken and divided up among his quarreling grandsons, feudalism took over to preserve the little law and order that prevailed during most of the Middle Ages. It was a system of government based upon a landed aristocracy. A Carolingian law of 847 made it mandatory for every freeman to place himself under the rule of a lord. Of the estimated sixty million people inhabiting Europe by 1300, more than ninety percent lived outside its towns and cities. The vast majority of these lived in villages on the manorial estates of feudal lords, themselves vassals to higher nobility, who generally oversaw the large land holdings (fiefs) of the church or of kings, princes, and noblemen. While life on the manor did not offer a variety of vocational choices or the freedom to follow other pursuits, it did provide stability for a society that felt the roof caving in and the walls crumbling all around it. Its foundation, while it showed some signs of shifting, remained intact. It was, after all, a sacral society in which the church, by its own admission and that of its popes, was supreme. Surely the church, with the support of the faithful, could fend off the Muslims and Jews and infidels. But the ordinary man would not have much say about just how this was done. He was at the mercy of the lord of the manor.

In a sense the peasants were only pawns in a real-life chess game. They represented the lowest class in medieval society, and they fared no better in the ranking of the church. It has been correctly said that life in the Middle Ages was organized into two hierarchies: that of the church and that of the state. At the top of the state’s hierarchy was the king, followed by lords, vassals, knights, freemen, and serfs. The class of serfs was further subdivided, and at the very bottom of the hierarchy was, occasionally, the class of slaves, a division dictated by heredity. Marriage could, upon occasion, change one’s status, but a career in the church offered the only sure avenue of escape for the low born. In the church—theoretically at least—a peasant’s son could become a pope, or if a converted Jew, a bishop. In practice, however, peasants’ sons more often became the parish priests. They lived in somewhat better housing than other peasants on the manor, but sons of the nobility became the princes (bishops) of the church.

The stratification of medieval society was dramatized both by dress and by architecture. The nobility were distinguished from the commoners by their regal trappings: the ermine cape, the bejeweled medallion, the high leather boots. The lord of a manor lived in a manor house, if not a castle, and kings, lords, and vassals as well as knights occupied well-fortified castles. The two most prominent buildings in a manor village, in fact, were the parish church and the manor castle.

As inadequate as the feudal system was, from almost any standpoint it was better than chaos. Besides, it did make some positive contributions to medieval life. It developed the three-field system, which has been called the most important advance in agriculture that the Middle Ages produced. It also created communities in which cooperation in the equitable distribution of the peasants’ allotted acreage became a matter of communal decision, thus providing the peasants with some degree of economic security. At the very least, feudalism made possible the bare essentials of government without which civilization could hardly have survived.

THE MEDIEVAL CHURCH

To the eyes of the casual observer, the parish church, the monastery basilica, and the bishop’s cathedral were the most prominent features of any medieval skyline. And even if architecture had not conveyed this fact, the constant ringing of the bells from countless church towers surely would have. Every manor had its parish church, and its priest was easily the most important personage in the community. As rapidly as towns and cities began to develop, church steeples and towers rose against the horizon, frequently dwarfing all other buildings in sight. These structures, sometimes splendid, were medieval man’s monument to his faith. For whatever else he may have been, he was basically a religious man, intent on saving his soul. It is difficult to escape the impression that the times were, indeed, an “Age of Faith.”

Monasticism

Symbolic of the devotional life of the medieval church was the monastic movement. Arising in the East, it was soon adapted by the organizing genius of Western Christianity. The Benedictine order, founded by Saint Benedict of Nursia (ca. 530), provided the prevailing rule upon which numerous orders were established. In some respects monasticism may be viewed as an attempt to reform the church, which was rapidly becoming captive to its culture. But by the tenth century it was painfully evident that monasticism itself was decadent and in need of reform. Revival came in the tenth century when a monastery was founded at Cluny based upon a revised form of the Benedictine rule. Before the Cluniac reform had run its course, more than eleven hundred new monasteries had been founded, and the Cluniacs had become the most aggressive and influential order in the medieval church, placing their members among the upper echelons of the hierarchy, including the papacy itself. Success took its toll, however, and still another monastic order was founded, this time at Cîteaux in 1098. This order sought to improve upon the revised rule of the Cluniacs with yet another revision. Bernard of Clairvaux, the caustic critic of Abelard and author of the hymn “Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee,” became the most ardent promoter of the Cistercian movement, organizing sixty-five new houses himself.

However, the monastic ideal found its most famous embodiment in Saint Francis of Assisi (1182-1226). Previous monastic orders had looked inward, concentrating on the cultivation of the devotional life. Saint Francis reversed this emphasis. To some extent his work and the new shape of the mendicant orders had been anticipated in the life and work of Saint Bernard. To the familiar vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience the Franciscans added the vows of preaching and begging. While the older orders remained cloister-bound, the Franciscans were mobile. Saint Francis and his early followers took the vow of poverty seriously. They did not attempt to make a comfortable living; instead they dedicated themselves to the care of the sick and the outcasts of society. The Franciscans also became the first of the mendicant orders to actively engage in mission work. They were given tentative recognition in 1210. They rapidly won other adherents, including women—in fact, a second order was founded as the female counterpart of the original. However, as Pope Innocent had feared, the asceticism of Saint Francis and his most ardent followers was much too severe for most would-be Franciscans. As the order grew more lax, certain Franciscans formed splinter groups in an attempt to keep faith with the ideals of the saint from Assisi. Consequently the Franciscans became so notorious for their schismatic tendencies that they were frequently referred to as the “Franciscan rabble.”

Yet Saint Francis had succeeded in setting a new pattern for medieval monasticism. Following the formation of his order, three other major mendicant orders arose: the Dominicans (1216); the Carmelites (1229), an order formed by crusaders on Mt. Carmel, who claimed Elijah as their founder; and the Augustinians (1256), who took the name of the famous bishop of Hippo for their own. Although they shared a similar vision, the orders became quite different, not only in dress but in character. In time the Franciscans, despite their tendency to quarrel, became the most important missionary order. The Dominicans became renowned for both their scholarship and their nose for heresy. And the Carmelites faded into the background as the Augustinians forged ahead, vying with the Dominicans for the most important chairs of theology in the new universities that were being established in every part of Europe.

In the wave of religious enthusiasm that swept over Europe in the High Middle Ages, laymen formed semimonastic orders that also served the church. Closely associated with the Spiritual Franciscans were the Beguines (women) and the Beghards (men). Although they did not take monastic vows, they followed a simple life-style, combining contemplation with service to the sick and needy. They were suspected of heresy.

Mysticism sparked by the preaching of Gerhard Groote (1340-1384) spawned still another semimonastic lay movement known as the Brethren of the Common Life. The Brethren became famous for the Latin schools that they established in the Netherlands and Germany. Their houses were composed of laymen marked by their sincerity and learning. However, most lay people of medieval Europe were both illiterate and credulous, content to express their religious fervor in other less demanding and more entertaining ways—hence the pilgrimage movement.

The Pilgrimage Movement

In his Canterbury Tales Chaucer gives an incisive glimpse into the pilgrimage movement as it had developed in England by the fourteenth century. Here one learns of the worship of both patron saints and often-fraudulent relics such as the Pardoner’s “Our True Lady’s veil” and his bottle of pig’s bones. After mentioning a few of the Pardoner’s “relics,” Chaucer concludes, “And thus, with flattery and such like japes, / He made the parson and the rest his apes.” As Chaucer portrays so vividly in his character sketches of the twenty-nine pilgrims who happened to meet at Tabard Inn while en route to Canterbury to visit the shrine of the famous English saint, Thomas à Becket of Canterbury, the pilgrimage movement held an attraction for all classes of medieval society. The tales told by Chaucer also give the reader a glimpse into the nature of popular piety. Apparently that which was characteristic of England was also—allowing for some regional variations—characteristic of Europe.

At a comparatively early date, relics of the martyrs were becoming objects of veneration and worship. Such practices received unprecedented support during the Cluniac ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- Prologue

- Chapter I: A Medieval Montage

- Chapter II: The Italian Renaissance

- Chapter III: Renaissance Art and Artists

- Chapter IV: The Northern Renaissance

- Chapter V: Attempts at Reform: Wycliffe and Huss

- Chapter VI: Erasmus and His Disciples

- Chapter VII: Europe on the Threshold

- Chapter VIII: Martin Luther: The Strategy of Confrontation

- Chapter IX: New Wineskins for New Wine

- Chapter X: Zwingli: Humanist Turned Reformer

- Chapter XI: The Parting of the Ways

- Chapter XII: The Anabaptists

- Chapter XIII: Calvin and the City of Refuge

- Chapter XIV: The Reformation Comes to England

- Chapter XV: The Catholic Revival

- Chapter XVI: Conflict and Change

- Epilogue

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Renaissance and Reformation by William R. Estep in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.