- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

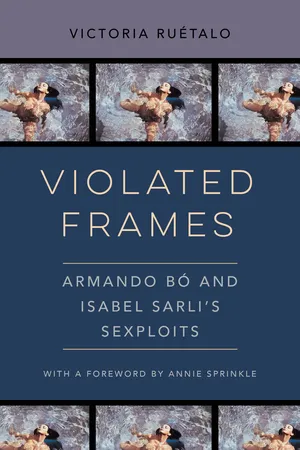

When Armando Bó and Isabel Sarli began making sexploitation films together in 1956, they provoked audiences by featuring explicit nudity that would increasingly become more audacious, constantly challenging contemporary norms. Their Argentine films developed a large and international fan base. Analyzing the couple's films and their subsequent censorship, Violated Frames develops a new, roughly constructed, and "bad" archive of relocated materials to debate questions of performance, authorship, stardom, sexuality, and circulation. Victoria Ruétalo situates Bó and Sarli’s films amidst the popular culture and sexual norms in post-1955 Argentina, and explores these films through the lens of bodies engaged in labor and leisure in a context of growing censorship. Under Perón, manual labor produced an affect that fixed a specific type of body to the populist movement of Peronism: a type of body that was young, lower-classed, and highly gendered. The excesses of leisure in exhibition, enjoyment, and ecstasy in Bó and Sarli's films interrupted the already fragmented film narratives of the day and created alternative sexual possibilities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Violated Frames by Victoria Ruétalo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Bodies and Archives

CHAPTER 1

Bodies through Time . . . Time through Bodies

I consider myself a fighter, a woman of the people.

—Isabel Sarli, 19991

On 12 October 2012, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner proclaimed Isabel Sarli an ambassador of Argentine popular culture. The decree declares:

Ms. Isabel Sarli is considered a true representative of national culture, as much due to her talents as film actress as for being deemed a popular icon of her time and an emblematic celebrity of Argentine cinema.2

It authenticates a new perspective on the sensual star as one who “links the ethic and cultural values, in representing the synthesis of the image that the Argentine Republic wishes to project to the world.”3 Sadly, the words of validation arrived fifty-four years after the release of Sarli-Bó’s debut film, a shocking launch that founded a body of work that was never officially sanctioned by the many governments in power during the development of their careers. They experienced censorship from their first public experiment.

This more recent gesture to recognize the star, under one of the latest iterations of General Juan Domingo Perón’s original party, recalls a similar directive bestowed upon the naïve young woman who had won the title of Miss Argentina in 1955. Before heading to California for the Miss Universe pageant, Sarli met then President Perón, who distinguished her value by her beauty.4 He said the following words to her:

You are worth more than 20 Ambassador Paz [the Argentine ambassador to the United States] because you represent the beauty of the Argentine woman, and you bring with you a message of good will to the people of the universe.5

The connection founded early on between the up-and-coming starlet and Peronism was only reaffirmed more recently in Sarli’s old age, after the once scandalous films had become nostalgic relics of a distant era. Time left a mark on her onscreen body, but her latest recrowning as national ambassador formally acknowledges the central role the duo had on popular culture and sexual norms, and the enduring affect they still hold for Argentine audiences. Their role explains the ever-changing nature of narrations and mythology based on taste, stories that have a way of soothing past wounds. The official celebration that came years later did not remove the scars left on the sexual body but only helped to highlight the ironies found in Sarli’s aging figure and promote the watered-down body of films widely available today on YouTube. This chapter returns to the historical context of 1960s’ and 1970s’ Argentina to gather the many differing and at times contradictory scenarios that surround the work and moment of the Bó-Sarli brand, in order to understand the traumatic wounds of history left on the body of the star and the oeuvre Sarli-Bó produced.

Diana Taylor explains that both narratives and scenarios help understand and better analyze histories. By using the term scenario to approach social structures and behaviors, Taylor draws from both the repertoire and the archive.6 Simply put, the archive holds the enduring materials that are passed on from generation to generation, and the repertoire enacts embodied practice, memory, and knowledge.7 For Taylor, scenarios carry localized meaning that pass as universally valid. As in Michel de Certeau’s sense, they are practiced places, actions, and performances embodied by social actors. They are Pierre Bourdieu’s habitus: structures that allow for reversal, parody, and change but remain generally fixed, imploring us to situate ourselves in relation to the scenario. And it is through scenarios that the archive and repertoire work together to constitute and transmit social knowledge.8 The repertoire of the body operates in conjunction with the archive of history to create references that are by no means complete, a context that is always in the process of becoming because it is beyond total capture. As snippets in time that help fill in the picture of the past, scenarios also remind us that the portrait is permanently unfinished. They are mediated like the repertoire and the archive, a product of relationships, exchanges, and fluctuations rather than stability. By interweaving both narratives from the Bó-Sarli films as archives and histories from distinct and handpicked but interrelated events surrounding the merging of an assemblage of histories and contexts, I articulate how the Bó-Sarli films relate, react, and absorb such forces. The historical events and topics include Eva Perón’s body, the founding supporters of Peronism, classed taste, the emergence of the category of youth, and the context of onscreen sexuality—all of which effected the changing dynamics of Argentina from 1955 to 1983. I also highlight the conflating scenes that gave meaning and produced affect to eventually allow the belonging of the duo’s work in Argentine society, one that has more recently come with official acknowledgement in the law.

While Armando Bó was not a Peronist (he instead was affiliated with the Radical Party) there were elements in his work that could certainly align with the Justicialista movement, another name given to General Perón’s party. Isabel Sarli, on the other hand, was an ardent Peronist at the time, a commitment sealed with her meeting the general as the representative for Argentina in the Miss Universe pageant. In this chapter I will begin with the premise that to explore the Sarli-Bó films one must understand the specific political and social scenarios from which their work draws inspiration, a time that coincides with the exile and return of Perón and the 1976 dictatorship that followed.

The period between 1955 and 1973 was an important and volatile time in the history of Argentina. It is also a period in which twenty-three of the twenty-seven Sarli-Bó films were produced. In the span of eighteen years there were nine different governments, only three of which were elected democratically (Arturo Frondizi, Arturo Umberto Ilia, and Héctor Campora). The rest gained power through military coups and in some cases from internal coups within the military, like those orchestrated by Roberto M. Levingston (in June 1970) and Alejandro Agustín Lanusse (in March 1971). Remarkably, until the Campora government in 1973, the constant absence from the political scene was Juan Perón and the Justicialista party, which was proscribed from its ouster until 11 March 1973, when Lanusse announced presidential elections and allowed a candidate to run for the first time since the leader’s exile. For another three years the instability continued under a Peronist government, until the 1976 coup that brought in the most brutal dictatorship in Argentina’s recent history.

Evident during the unstable stretch is the constant disavowal of Peronism and its meaning from public spaces. The movement and its leader were repeatedly erased from the public sphere in a way that ironically created an aura surrounding Perón’s role in the nation’s past. By discussing Peronismo and how its aura evolved, beginning with the body of Perón’s second wife, I contextualize the work of Sarli-Bó. As Peronismo was the absent present during the era in question, I argue that the pair borrowed from the movement’s tradition and melodrama, and appealed to its base (so-called cabecitas negras and working-class men), becoming most popular in marginalized areas around Buenos Aires and the rest of the country, much like the political faction itself.9 Furthermore, their films (excessively affective melodramas with themes of social justice showing the plight of the marginalized), which featured a public anti-intellectual stance, were very much in line with its populist politics. Could the difficulty Bó-Sarli had with the censors be in part due to this seeming alignment?

To grasp the social, economic, and political factors surrounding the films, I delve into the support base of Peronism as it evolved from its foundation in different forces—working-class men, women, and youth—developments determining their spectators. The arguments that follow go beyond looking at the concrete base of their audience; I can only speculate retrospectively on this question by inductively coming to such a conclusion.10 Instead, I connect Peronism’s affective mode, which I argue can be found within Eva’s body, to questions of taste linked to the group, trying to develop the historical base for the chapters that follow. As the lowly body of Peronism threatened to return, so did the possibility of sex that was imminent both in society and onscreen, a menace found in the material female body. In part, the complicated story for both the movement and the filmmaking practice relates to belonging and excess. Analogously, Peronism and the Sarli-Bó films provided a place for excessive bodies to belong in the nation and on the movie screen, despite the many risks that impended and endangered their existence, showing a fissure in that very system. I begin by explaining what I mean when I refer to Peronism’s affective mode, which surfaces with Eva’s body and consummates in the appearance and complete uncovering of Isabel’s cuerpo.

SCENARIO 1: EVA PERÓN AND THE POLITICS OF AFFECT

In La pasión y la excepción, Argentine cultural critic Beatriz Sarlo brings together three narratives—the disappearance of Eva Perón’s corpse after it was embalmed, the assassination of Pedro Eugenio Aramburu, president from 1955 to 1958 and leader of the conservative “liberating revolution,” and two fictional short stories by Argentina’s most prominent author Jorge Luis Borges—to discuss the role of affect in Argentina in the early 1970s and create one scenario. Playing off of Copi’s interpretation of Eva in the theatrical piece Eva Perón, which debuted in Paris in 1970, Sarlo turns to her exceptionality as the founding element of the book that binds all three references. Because the ultimate and defining incident for her study is the disappearance of Eva’s deceased body, Sarlo focuses on the construction of her figure while she was alive to show the journey it takes to become “sublime” after her death, a quality that refers to the work of Emmanuel Kant in describing unquantifiable greatness.11

Sarlo argues that Eva was exceptional among her peers and that her body personified a melodrama and camp aura during her lifetime. When compared to other colonel or political wives, Eva was not representative of the normative; conversely, she was thin, young, and blonde, more akin to a model than the mother or typical housewife body of other spouses.12 Eva had a past: as a rising radio and film star, her overall image was defined by the extravagant fashion she flaunted. In one of her roles in La cabalgata del circo (Circus Cavalcade, Mario Soffici, 1944), she acted alongside Bó. Early on in her career, Paco Jamandreu designed her wardrobe and helped to conceptualize Eva’s aura, an ultramodern look that could be described as fitting somewhere between Greta Garbo and Audrey Hepburn.13 Her business suits hid the fact that she had no curves. The androgynous guise, at a time when women’s fashions were homogenous, contributed to Eva’s extraordinariness. Androgyny exceeded her style and seeped into her gestures, mannerisms, and actions.14 For instance, Eva was comfortable with men. She addressed the opposite sex informally, a behavior that pushed the limits for women in the 1940s. Later Eva wore the most fashionable designer brands from Paris, an excess of elaborate dresses and jewelry helping to reaffirm her rags-to-riches story.

“Performatic” moments helped to define Eva’s body, moving from melodramatic and camp to the religious realm in the end.15 When she became sick, her celebrity deviated toward the tragic and “sublime,” a quality reached through her passionate excess of hyperbolic cliché and redundancy. Her sublimity created a type of “auratic” in the Benjaminian sense, a presence that lives beyond the material now. As Taylor asserts, Eva’s body ensures her reality and thus provides the authenticating materiality that sustains the performance of resuscitation.16 After her death in 1952, her beauty and wealth were preserved as if at their peak by the latest embalming techniques. An expensive proposition to produce the most elaborate corpse at US $200,000, but Eva’s body became the trace that threatened to reappear.17 Ironically, the body gives authenticity to both ideological sides, the pro- and anti-Perón movements, as it takes on the authority of the regime and both sides work hard to capture and fix it: “to make and unmake” her myth, to borrow a 1987 phrase from Elaine Scarry. Eva Perón’s body lies in the realm of the symbolic, as Sarlo states, but Sarlo’s analysis of the archive (body as archive) alone only goes thus far, for she remains at the level of representation. Sarlo acknowledges that Eva’s body produces a type of affect that justifies love/admiration on the one hand and hate/disgust on the other but does not emphasize enough its lingering power into the present. Sarlo’s study is a first attempt to analyze how Peronism’s affect through its excess created a sense of (not) belonging, a strategy that impacted the post-Peronist moment that followed, thereby leaving a trace or a wound that was never really reconciled and always threatens to return.

The affect found in the living and dead body of Eva can help reflect on the power of the movement’s attraction. Affect, more than emotions, describes the body’s capacity to move and be moved physically. From a Spinozian perspective, the body’s perpetual becoming never reaches a final state but is in constant transformation.18 Affect itself describes excess that cannot be fully represented, articulated, or defined. A surplus gap between what is meaningful and knowable and what is livable can never be erased, is beyond representation, and thus instead stands in for the remainder of the representable. The shift from thinking about bodies as material entities with defining qualities to one of belonging or not reflects the shift from identity politics to a politics of belonging not based on the concept of essence. While Sarlo’s example of Perón isolates her, it also muffles the history and becomings of bodies that surrounded her and mutes those stories by emphasizing only the exceptionality of Eva, the commodity or star. What about the faceless bodies of the masses that surrounded her? How did their bodies belong to the project that became known as Peronism? Or how did bodies reject her aura through the anti-Peronist movement? How does the body of the exceptional relinquish political, economic, and symbolic capital to the have-nots? What emotional ties are provoked by such invocations of the past? If Eva’s body was an archive of memory, then how is her body threatening to return? And what traces in popular...

Table of contents

- Subvention

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Note on Translation

- Foreword by Annie Sprinkle

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Signature of a “Bad Cinema”

- Part I: Bodies and Archives

- Part II: Censoring Bodies in Labor and Leisure

- Conclusion: “You won with the censors. . . . They couldn’t stop you!”

- Notes

- Selected Filmography

- Index