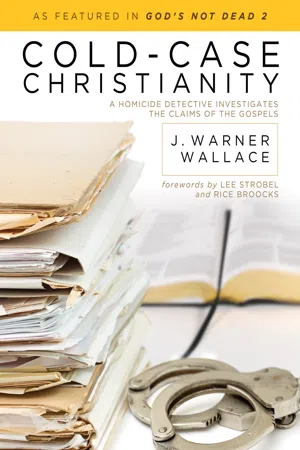

Chapter 1

Principle #1:

DON’T BE A “KNOW-IT-ALL”

“Jeffries and Wallace,” Alan barked impatiently as the young officer scrambled to write our names on the crime-scene entry log. Alan lifted the yellow tape and passed beneath it, crouching painfully from the stress he had to place on his bad knee. “I’m getting too old for this,” he said as he unbuttoned the coat of his suit. “The middle of the night gets later every time they call us out.”

This was my first homicide scene, and I didn’t want to make a fool of myself. I had been working robberies for many years, but I had never been involved in a suspicious death investigation before. I was worried that my movements in the crime scene might contaminate it in some way. I took small, measured steps and followed Detective Alan Jeffries around like a puppy. Alan had been working in this detail for over fifteen years; he was only a few years short of retirement. He was knowledgeable, opinionated, confident, and grumpy. I liked him a lot.

We stood there for a moment and looked at the victim’s body. She was lying partially naked on her bed, strangled. There was no sign of a struggle and no sign of forced entry into her condominium, just a forty-six-year-old woman lying dead in a very unflattering position. My mind was racing as I tried to recall everything I had learned in the two-week homicide school I recently attended. I knew there were important pieces of evidence that needed to be preserved and collected. My mind struggled to assess the quantity of “data” that presented itself at the scene. What was the relationship between the evidence and the killer? Could the scene be reconstructed to reveal his or her identity?

“Hey, wake up!” Alan’s tone shattered my thoughts. “We got a killer to catch here. Go find me her husband; he’s the guy we’re lookin’ for.”

What? Alan already had this figured out? He stood there, looking at me with a sense of impatience and disdain. He pointed to a framed picture toppled over on the nightstand. Our victim was in the loving embrace of a man who appeared to be her age. He then pointed to some men’s clothing hanging in the right side of her closet. Several items appeared to be missing.

“I’ve been doing this for a long time, kid,” Alan said as he opened his notebook. “‘Stranger’ murders are pretty rare. That guy’s probably her husband, and in my experience, spouses kill each other.” Alan systematically pointed to a number of pieces of evidence and interpreted them in light of his proclamation. There was no forced entry; the victim didn’t appear to have put up much of a fight; the picture had been knocked over on the nightstand; men’s clothing appeared to be missing from the closet—Alan saw all of this as confirmation of his theory. “No reason to make it complicated, newbie; most of the time it’s real simple. Find me the husband, and I’ll show you the killer.”

As it turned out, it was a little more difficult than that. We didn’t identify the suspect for another three months, and it turned out to be the victim’s twenty-five-year-old neighbor. He barely knew her but managed to trick the victim into opening her door on the night he raped and killed her. She turned out to be single; the man in the photograph was her brother (he visited occasionally from overseas and kept some of his clothing in her closet). All of Alan’s presuppositions were wrong, and his assumptions colored the way we were seeing the evidence. Alan’s philosophy was hurting his methodology. We weren’t following the evidence to see where it led; we had already decided where the evidence would lead and were simply looking for affirmation. Luckily, the truth prevailed.

All of us hold presuppositions that can impact the way we see the world around us. I’ve learned to do my best to enter every investigation with my eyes and mind open to all the reasonable possibilities. I try not to bite on any particular philosophy or theory until one emerges as the most rational, given the evidence. I’ve learned this the hard way; I’ve made more than my share of mistakes. There’s one thing I know for sure (having worked both fresh and cold homicides): you simply cannot enter into an investigation with a philosophy that dictates the outcome. Objectivity is paramount; this is the first principle of detective work that each of us must learn. It sounds simple, but our presuppositions are sometimes hidden in a way that makes them hard to uncover and recognize.

SPIRITUAL PRESUPPOSITIONS

When I was an atheist, I held many presuppositions that tainted the way I investigated the claims of Christianity. I was raised in the Star Trek generation (the original cast, mind you) by an atheist father who was a cop and detective for nearly thirty years before I got hired as a police officer. I was convinced by the growing secular culture that all of life’s mysteries would eventually be explained by science, and I was committed to the notion that we would ultimately find a natural answer for everything we once thought to be supernatural.

My early years as a homicide detective only amplified these presuppositions. After all, what would my partners think if I examined all the evidence in a difficult case and (after failing to identify a suspect) concluded that a ghost or demon committed the murder? They would surely think I was crazy. All homicide investigators presume that supernatural beings are not reasonable suspects, and many detectives also happen to reject the supernatural altogether. Detectives have to work in the real world, the “natural world” of material cause and effect. We presuppose a particular philosophy as we begin to investigate our cases. This philosophy is called “philosophical naturalism” (or “philosophical materialism”).

Most of us in the Star Trek generation understand this philosophy, even if we can’t articulate it perfectly. Philosophical naturalism rejects the existence of supernatural agents, powers, beings, or realities. It begins with the foundational premise that natural laws and forces alone can account for every phenomenon under examination. If there is an answer to be discovered, philosophical naturalism dictates that we must find it by examining the relationship between material objects and natural forces; that’s it, nothing more. Supernatural forces are excluded by definition. Most scientists begin with this presupposition and fail to consider any answer that is not strictly physical, material, or natural. Even when a particular phenomenon cannot be explained by any natural, material process or set of forces, the vast majority of scientists will refuse to consider a supernatural explanation. Richard Lewontin (an evolutionary biologist and geneticist) once famously wrote a review of a book written by Carl Sagan and admitted that science is skewed to ignore any supernatural explanation, even when the evidence might indicate that natural, material explanations are lacking.

We take the side of science in spite of the patent absurdity of some of its constructs, in spite of its failure to fulfill many of its extravagant promises of health and life, in spite of the tolerance of the scientific community for unsubstantiated just-so stories, because we have a prior commitment, a commitment to materialism. It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, that we are forced by our a priori adherence to material causes to create an apparatus of investigation and a set of concepts that produce material explanations, no matter how counterintuitive, no matter how mystifying to the uninitiated. Moreover, that materialism is an absolute, for we cannot allow a Divine Foot in the door.2

Scientists aren’t alone; many historians are also committed to a naturalistic presupposition. The majority of historical scholars, for example, accept the historicity of the New Testament Gospels, in so far as they describe the life and teaching of Jesus and the condition of the first-century environment in which Jesus lived and ministered. But many of these same historians simultaneously reject the historicity of any of the miracles described in the New Testament, in spite of the fact that these miracles are described alongside the events that scholars accept as historical. Why do they accept some events and reject others? Because they have a presuppositional bias against the supernatural.

Bart Ehrman (the famous agnostic professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) was once in a radio debate with Michael Licona (research professor of New Testament at Southern Evangelical Seminary) on the British radio program Unbelievable?3 While debating the evidence for the resurrection, Ehrman revealed a naturalistic presupposition that is common to many historians. He said, “The bottom line I think is one we haven’t even talked about, which is whether there can be such a thing as historical evidence for a miracle, and, I think, the answer is a clear ‘no,’ and I think virtually all historians agree with me on that.” Ehrman rejects the idea that any historical evidence could demonstrate a miracle because, in his words, “it’s invoking something outside of our natural experience to explain what happened in the past.” It shouldn’t surprise us that Ehrman rejects the resurrection given this presupposition; he arrived at a particular natural conclusion because he would not allow himself any other option, even though the evidence might be better explained by the very thing he rejects.

MENTAL ROADBLOCKS

I began to understand the hazard of philosophical presuppositions while working as a homicide detective. Alan and I stood at that crime scene, doing our best to answer the question “Who murdered this woman?” One of us already had an answer. Spouses or lovers typically commit murders like this; case closed. We simply needed to find this woman’s husband or lover. It was as if we were asking the question “Did her husband kill her?” after first excluding any suspect other than her husband. It’s not surprising that Alan came to his conclusion; he started with it as his premise.

When I was an atheist, I did the very same thing. I stood in front of the evidence for God, interested in answering the question “Does God exist?” But I began the investigation as a naturalist with the presupposition that nothing exists beyond natural laws, forces, and material objects. I was asking the question “Does a supernatural being exist?” after first excluding the possibility of anything supernatural. Lik...