eBook - ePub

Resisting Brown

Race, Literacy, and Citizenship in the Heart of Virginia

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Many localities in America resisted integration in the aftermath of the Brown v. Board of Education rulings (1954, 1955). Virginia's Prince Edward County stands as perhaps the most extreme. Rather than fund integrated schools, the county's board of supervisors closed public schools from 1959 until 1964. The only formal education available for those locked out of school came in 1963 when the combined efforts of Prince Edward's African American community and aides from President John F. Kennedy's administration established the Prince Edward County Free School Association (Free School). This temporary school system would serve just over 1,500 students, both black and white, aged 6 through 23.

Drawing upon extensive archival research, Resisting Brown presents the Free School as a site in which important rhetorical work took place. Candace Epps-Robertson analyzes public discourse that supported the school closures as an effort and manifestation of citizenship and demonstrates how the establishment of the Free School can be seen as a rhetorical response to white supremacist ideologies. The school's mission statements, philosophies, and commitment to literacy served as arguments against racialized constructions of citizenship. Prince Edward County stands as a microcosm of America's struggle with race, literacy, and citizenship.

Drawing upon extensive archival research, Resisting Brown presents the Free School as a site in which important rhetorical work took place. Candace Epps-Robertson analyzes public discourse that supported the school closures as an effort and manifestation of citizenship and demonstrates how the establishment of the Free School can be seen as a rhetorical response to white supremacist ideologies. The school's mission statements, philosophies, and commitment to literacy served as arguments against racialized constructions of citizenship. Prince Edward County stands as a microcosm of America's struggle with race, literacy, and citizenship.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Resisting Brown by Candace Epps-Robertson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Rhetoric, Race, and Citizenship in the Heart of Virginia

Can the study of composition (literacy) serve the creation of a just commonwealth? If it can, how can it? What might emancipatory composition, a composition meant to set free the captives and give sight to the blind, be?

BRADFORD STULL, AMID THE FALL, DREAMING OF EDEN

[I]f we are to understand the nature of citizenship since 1957, and its requirements, we need to analyze the moment of desegregation, when the polity was coming unstitched and rewoven.

DANIELLE S. ALLEN, TALKING TO STRANGERS

On the evening of Sunday, September 15, 1963, many Black parents in Prince Edward County were preparing to send their children to school for the first time in four years. That same day, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, killed four young girls and injured many more. The news of the deaths from the fifteen sticks of dynamite Ku Klux Klan members had set in a place of worship shook the nation. Like the summer that preceded this horrific event, it marked a turning point in the civil rights movement. White supremacist violence at this level had not reached Prince Edward County and never did, but parents whose children would attend the opening day of the Free School on September 16 had no way of knowing that it would not. After four years with no public education, no one knew what to expect.

The September 16, 1963, issue of the Richmond Afro-American covered the story of the school’s opening alongside a column on the bombing. The civil rights movement often generated emotional highs and lows in short periods of time. This juxtaposition is highlighted by the newspaper’s stories on the devastation and deaths in Birmingham, with one article calling that city a “hell hole” and, beside it, another describing the “happiness and excitement” of the Black community for the Free School’s opening day (“Opening Day Ceremonies”). This first day of school was possible because of a culmination of struggle, persuasion, and steadfast belief that it was possible to restore educational opportunities to Prince Edward’s Black citizens.

Few court cases involving public education have garnered the attention and recognition of the Brown v. Board of Education rulings (1954, 1955). Brown ended separate but equal schooling on paper, ruling it unconstitutional. The doctrine of separate but equal had permitted state-sponsored segregation in public schools since the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, but the act of separation based on color was well established by both law and custom. Segregation had been the order of the day since slavery was instituted, as a means to uphold and protect the interests of plantation owners, and this lawful separation continued through numerous laws enacted after emancipation. Plessy v. Ferguson bolstered Jim Crow and Black codes by upholding state-sanctioned segregation based on race.

Prior to Brown, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) used the separate but equal doctrine to realize a number of legal victories that resulted in equal resource allocation to segregated schools in particular localities, but town-by-town legal battles quickly drained resources. Further, segregated schools had never been equal. NAACP executive secretary Lester Banks announced the need to press for integration as the only way for the Black community to “achieve their full dignity as citizens,” and as early as 1935 NAACP lawyers were building a legal strategy to support this effort (Kluger 477).1 As the United States sought to cultivate a reputation for supporting democracy around the world through its involvement in World Wars I and II, deeming this impression a critical weapon in the Cold War, the Black community demanded an end to the second-class status the separate but equal doctrine forced upon them.

The Supreme Court acknowledged through the Brown decision that segregation caused Black children to be deprived: “Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. . . . A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn” (Brown v. Board I 494). The ruling recognized the connection between public schooling and citizenship preparation: “Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. . . . It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship” (493). Citizenship, in this instance, was described as a role that could be attained through skill sets that could be offered in public schooling. While citizenship has myriad definitions, for the purposes of this book I am interested in the skills or traits that schools have historically offered students in a quest to groom young people for democratic life. Wan writes that “educative spaces have always been positioned as crucial elements of citizenship production,” but these spaces do not always thoroughly define what is meant by citizenship and how literacy helps one to achieve this status (17). Calling out the “ambient nature of the term ‘citizenship,’“ Wan builds on Graff’s work as she reminds us that without careful examination of what kind of citizenship is being sought after, or achieved, or what kind of literacy skills are believed to get one to that role, we fall short of unpacking “the implicit understanding that equality and social mobility are synonymous with and can be achieved through citizenship” (18). Part of understanding the ways in which literacy has been yoked to preparation necessary for citizenship comes from examining moments when education has been believed to be a way to “alleviate anxieties” during economic, social, or national moments of anxiety (Wan 16). As Brown sought to address the issue of segregation and inequality, it also expressed a reminder that public education was necessary for citizenship.

Prince Edward County’s board of supervisors responded to Brown through what they believed to be an expression of citizenship. Their statement, published in the county’s newspaper, expressed a desire to meet the needs of all the county’s citizens: “It is with the most profound regret that we have been compelled to take this action. . . . [I]t is the fervent hope of this board that . . . we may in due time be able to resume the operation of public schools in this county upon a basis acceptable to all the people of the county” (qtd. in Smith 151). This response reveals their fear of the impact Brown could have on those invested in maintaining control over the Black community.

Brown, at its core, was about securing through integration the same educational resources and opportunities for Black students that whites already enjoyed; however, the ruling did not supply a framework for the unraveling of segregation. Thurgood Marshall, head NAACP lawyer for the Brown case, told news outlets that he was “cautiously optimistic” about the ruling; he said that if white people tried to defy the high court “in the morning, we’ll have them in court the next morning—or possibly that same afternoon” (qtd. in Pratt 3). The second Brown ruling, delivered in May 1955, attempted to provide guidance for implementation, calling for an end to segregation with “all deliberate speed” (Brown v. Board II 301), but this proclamation was vague with regard to procedure and process, and white resistance became palpable both in the streets and in the state legislatures. As I recount here, in Prince Edward County the resistance had been brewing for quite some time.

Danielle Allen contends that Brown triggered “anxieties of citizenship,” and in the years following the Brown ruling US society had to consider what citizenship meant when one group was no longer systematically and legally excluded from participating with the majority (4). As the epigraph to this chapter suggests, Brown redefined both public education and citizenship. The Brown ruling, its precipitating events, and responses to it reveal the full spectrum of discourse on constructions of American citizenship.

Catherine Prendergast argues that the post-Brown era did not live up to its expectations, and she asserts that the high court’s decision reflects thinking “on a grand scale that the rationale in Brown for ending legalized segregation rested on defining public education as the precursor to good citizenship” (17). She acknowledges the connection the ruling made between citizenship and education; however, Prendergast challenges the ways in which Brown reified literacy as a “white property,” thus continuing to damage the prospect of racial justice and social reform. Her argument holds that an understanding of literacy as a set of transferable skills, which can be granted to or shared with marginalized communities by those in power, does little to advance social justice. Prendergast demonstrates that “throughout American history, literacy has been managed and controlled in a variety of ways to rationalize and ensure white domination” (2). Whether this happened through laws forbidding slaves to learn to read and write or through the unequal allocation of funding for segregated schools, literacy has been a means by which whites can exert control over Black communities. Post-Brown Prince Edward County exemplified this stance, as white community leaders continued to take it upon themselves to control access to education and to prescribe what citizenship could and could not look like for Black people. The Free School’s restoration of free public education to the community was another endeavor to challenge these ideologies.2

A History of Prince Edward County’s Battle for Equal Education

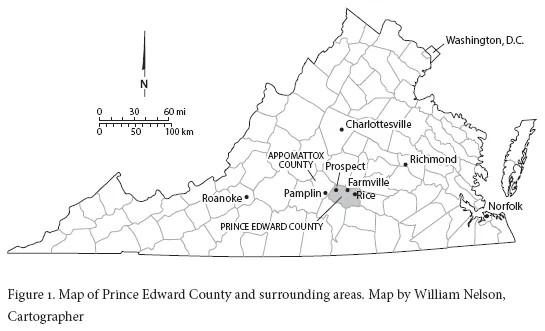

Prince Edward County sits sixty miles southwest of Richmond, the capital of Virginia, in the center of the state. This rural, central Virginia county was formed in 1754. Much of the county’s prosperity in its first century came from the rich cash crop of tobacco, but plantations also produced wheat, corn, dairy products, and livestock (Adams and Rainey 47). Early relationships between Blacks and whites as slaves and masters varied across the region. While slavery was assuredly the norm of the day, historians have discovered that there were some anomalies. The owner of Bizarre plantation near Farmville, Richard Randolph released the slaves he had been given by his father. Randolph’s will declared the evils of slavery, “expressing . . . abhorrence of the theory, as well as [the] infamous practice, of usurping the rights of our fellow creatures, equally entitled with ourselves to the enjoyment of liberty and happiness” (qtd. in Adams and Rainey 49). Randolph’s slaves, freed in 1796, would settle on a parcel of land at Bizarre known as Israel Hill, making “the Farmville community unique among antebellum southern towns” because of its large number of free Blacks before emancipation (Adams and Rainey 50).3 Before the Civil War the 1860 census reported that 44 percent of the population was made up of whites, 16 percent free Blacks, and slaves made up the remaining 40 percent (Adams and Rainey 51). The population demographics would remain relatively consistent throughout the middle of the twentieth century, with whites finding themselves in the minority. According to data collected by the US Census Bureau in 1950, the population of Prince Edward County was 15,398, with 55 percent (8,538) listed as white and 45 percent (6,860) as nonwhite. In 1960, the Census Bureau indicated that population of Prince Edward had decreased to 14,121. However, the percentage of the population listed as white increased to 60 percent (8,488), and the nonwhite population decreased to 40 percent (5,633). Of the nonwhite population, all but two individuals were listed as Black (US Census 1950 46–86; US Census 1960 48–65).

While freedom on paper would come for the Black community with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction eras found many free Blacks facing the challenge of navigating their newfound freedom in the face of continued social stratification across the South, and Prince Edward was no different. In part, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, respectively, were rendered useless with Plessy v. Ferguson’s affirmation of Jim Crow laws that maintained white control through segregation.

A visit to Farmville by W. E. B. Du Bois in July 1897 led to a report titled “The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia: A Social Study.” Du Bois detailed the community’s attempts to be self-sustaining and independent in the face of segregation. He reported that there were no Black schools in Farmville. Instead, there was a district school operating in the county. The school, with one male principal and four assistants, was considered unsuccessful because of its lack of resources and teachers. There were few work opportunities in Farmville, with many in the county working the land to feed their families. In spite of these conditions, Du Bois noted, there was an “adjusted interdependence” between Blacks and whites (23). In part, this adjusted interdependence represented the types of relationships between Blacks and whites in many rural localities where agricultural work often required joint effort, no matter the color of one’s skin. Prince Edward was no different, with farming neighbors often helping one another at harvest time, no matter their skin color (Berryman).

Nonetheless, Jim Crow kept public spaces separated. As in most communities, while separate schools in Prince Edward meant inferior conditions for Black students, that did not always mean teachers who were not dedicated and motivated enough to have their pupils learn or parents who did not rally to support the education of their children. Vanessa Siddle Walker’s careful analysis of segregated Black schools has demonstrated that “history most often focuses on the inferior education that African American children received” (1). Rather, “historical recollections that recall descriptions of differences in facilities and resources of white and Black schools without also providing descriptions of the Black schools’ and communities dogged determination to educate African American children have failed to tell the complete story of segregated schools and the parental and community support African American children did have” (4–5). Kara Miles Turner’s work does just that for Prince Edward. In “‘Getting It Straight’: Southern Black School Patrons and the Struggle for Equal Education in the Pre-and Post-Civil Rights Eras,” she details the numerous instances in which Black parents in Prince Edward sought improvements in their children’s schools, including repairing buildings, longer school terms, and transportation. Early county records, predating Du Bois’s visit, show that Blacks steadily petitioned the school board for better teachers and resources for their schools. In 1882, a county school board report described six Black citizens of the county who had petitioned the school board in Farmville for colored teachers who were as competent as those in the white schools. The school board denied this request. Prior to the late 1930s, the county required Black parents to subsidize teachers’ salaries to keep their schools open as many days as white schools stayed open with full state funding (Turner, “‘Getting’“ 221). Parents contributed out of pocket the funds for books and building maintenance while also footing the bill for white students through their county taxes. These inequalities continued well into the middle of the twentieth century before the Black community reached its tipping point.

On April 23, 1951, students at Robert Russa Moton High School, the county’s only Black high school, planned and executed a walkout under the leadership of sixteen-year-old Barbara Rose Johns.4 Protesting the poor conditions of the schools, the students would meet with the superintendent and county school board to voice their frustrations. Oliver Hill and Spottswood Robinson, lawyers from Richmond’s NAACP, came to Farmville to investigate, and the NAACP filed suit. In the filing for Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County the plaintiffs demanded school desegregation, calling “separate but equal” a sham. The NAACP combined the case with four others: Briggs v. Elliott (South Carolina), Gebhart v. Belton (Delaware), Bolling v. Sharpe (Washington, DC), and Brown v. Board of Education (Kansas); combined, they would come to be known as Brown. The Prince Edward Black community’s involvement in the quest for equitable education was present from the beginning of the civil rights era, as was resistance from the white community.

The county’s journey toward negating the Brown ruling began in April 1955. Members of the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties, a group formed to protect segregation, visited the Prince Edward County Board of Supervisors to voice their opposition to integrated schools. The Defenders were spread across Virginia but had an especially large membership in Prince Edward because the group’s president, Robert Crawford, was a local business owner. Defenders also sat on the county’s board of supervisors. In Brown’s Battleground: Students, Segregationists, and the Struggle for Justice in Prince Edward County, Virginia, the historian Jill Ogline Titus describes as “pillars of the community” these men who told the board that they would not support taxes that contributed to integrated schools. They were able to sway the board to postpone a decision on the budget. The following month, on May 31, 1955, when Brown II was released and “all deliberate speed” became the threat to segregation, concerned white citizens once more approached the board to ask them to halt any appropriation of funding for schools. Board members acquiesced and passed only a small operating budget—enough to cover building upkeep but not enough to operate a school system (Titus 27).

Meanwhile, in June 1955 the Prince Edward Educational Corporation was established. This corporation’s goal was to ensure private, segregated education for white children in the event of forced integration and school closures. Within the summer the corporation raised $180,000 in pledges, surpassing the monthly budget being allotted for the entire Prince Edward County public school system. Public schools would reopen for the 1955–56 school year, but the corporation kept its pledges, just in case alternative schooling was necessary (Titus 30).

At the close of the 1956 school year, white residents would once more voice their support for limiting the budget of the public school system as a precautionary measure against the threat of integration. The May 3, 1956, public hearing on the county’s budget for the 1956–57 school year was met with support when board members voted to continue passing a heretofore policy, which meant that it passed a budget for only thirty days at a time (Titus 30). That same evening, the county’s board of supervisors received a “Declaration of Convictions” signed by more than four thousand white citizens of Prince Edward. The manifesto acknowledged their support for the abandonment of public schools should integration become mandatory, citing their preference to “abandon public schools and educate our children in some other way if that is necessary to preserve segregation of the races in the schools of the county” (qtd. in Titus 31). Segregated schools would continue to operate for the 1956–57 and 1957–58 school years.

Prince Edward’s proponents for segregation felt some level of reprieve when a district court judge, Sterling Hutcheson, ruled that Prince Edward would have until September 1965 to comply with the desegregation order. Judge Hutcheson, from the Fourth District Court, referenced his knowledge of the area and culture, rather than legal precedent, in what was clearly a departure from Brown II. When the state’s Court of Appeals reversed his opinion in 1958, Hutcheson ruled that Prince Edward could have until 1965 to integrate. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the ruling once more i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface. A Genealogy through Stories

- Introduction. The Power, Possibility, and Peril in Histories of Literacy

- Chapter 1. Rhetoric, Race, and Citizenship in the Heart of Virginia

- Chapter 2. Manufacturing and Responding to White Supremacist Ideology in the “Virginia Way”

- Chapter 3. “Teaching Must Be Our Way of Demonstrating!”: Institutional Design against White Supremacy

- Chapter 4. Free School Students Speak

- Chapter 5. Pomp and Circumstance: The Legacy of the Prince Edward County Free School Association for Contemporary Literacy Theory and Pedagogy

- Appendix. Timeline of Key Local, Regional, and National Events Related to Civil Rights

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index