The Semantics of Word Division in Northwest Semitic Writing Systems

Ugaritic, Phoenician, Hebrew, Moabite and Greek

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Semantics of Word Division in Northwest Semitic Writing Systems

Ugaritic, Phoenician, Hebrew, Moabite and Greek

About this book

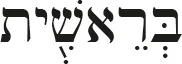

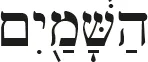

Much focus in research on alphabetic writing systems has been on correspondences between graphemes and phonemes. The present study sets out to complement these by examining the linguistic denotation of markers of word division in several ancient Northwest Semitic (NWS) writing systems, namely, Ugaritic, Phoenician, Moabite, and Hebrew, as well as alphabetic Greek. While in Modern European languages words on the page are separated on the basis of morphosyntax, I argue that in most NWS writing systems words are divided on the basis of prosody: 'words' are units which must be pronounced together with a single primary accent or stress, or as a single phrase. After an introduction providing the necessary theoretical groundwork, Part I considers word division in Phoenician inscriptions. I show that word division at the levels of both the prosodic word and of the prosodic phrase may be found in Phoenician, and that the distributions match those of prosodic words and prosodic phrases in Tiberian Hebrew. The latter is a source where, unlike the rest of the material considered, the prosody is well represented. In Part II, word division in Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform is analyzed. Here two-word division strategies are identified, corresponding broadly to two genres of text: viz, literary, and administrative documents. Word division in the orthography of literary and of some other texts separates prosodic words. By contrast, in many administrative (and some other) documents, words are separated on the basis of morphosyntax, anticipating later word division strategies in Europe by several centuries. Part III considers word division in the consonantal text of the Masoretic tradition of Biblical Hebrew. Here word division is found to mark out 'minimal prosodic words'. I show that this word division orthography is also found in early Moabite and Hebrew inscriptions. Word division in alphabetic Greek inscriptions is the topic of Part IV. Whilst it is agreed that word division marks out prosodic words, the precise relationship of these units to the pitch accent and the rhythm of the language is not so clear, and consequently this issue is addressed in detail. Finally, the Epilogue considers the societal context of word division in each of the writing systems examined, to attempt to discern the rationales for the prosodic word division strategies adopted. Contexts of and Relations between Early Writing Systems (CREWS) is a project funded by the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 677758), and based in the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- 1. Introduction

- Part I Phoenician

- Part II Ugaritic alphabetic cuneiform

- Part III Hebrew and Moabite

- Part IV Epigraphic Greek

- Bibliography