![]()

1

Spotlighting the Bible’s Blind(ing)spots

Jione Havea and Monica Jyotsna Melanchthon

In the media age, steered by the transmutations of artificial intelligence, “coding” identifies products and genes as well as traces the locations and movements of genetic strands, of tagged bodies (surveillance), and of operations. While tracking is helpful (but not necessarily ethical) in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic—at the genetics level, to track the mutation of the SARS-Cov-2 coronavirus and at the social level, to identify contacts and reduce the chance for spreading infection—surveillance disturbs a lot of people. Tracking devises might be ethical when used with people on parole, but not for “free” persons whether infected or not.

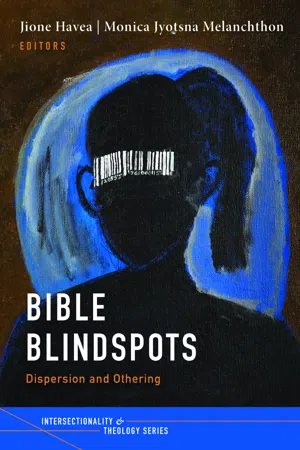

In the media age, in the whitewash of poverty and the rapture of human trafficking, some women and children have become products to be sold and bought, used and discarded like damaged and expired goods. Such situations are exposed and challenged in the “untitled” painting by Maria Fe (Peachy) Labayo on the cover of this book (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Maria Fe (Peachy) Labayo, “Untitled” (2016, detail). Used with the permission of the artist

The human body is blackened, with no facial features; it is a female body, because of the hair, and she could be a young person. She wears glasses, as if to invite viewers to see her as well as to be seen by her, and her glasses also look like handles on a trophy—she represents the trafficked bodies that have become the prize for the highest bidder. This painting also functions as a mirror, for viewers to see how, when they buy a barcoded product, they might be contributing to human trafficking and to the defacing of those who are trafficked. Human trafficking is not a phenomenon; human trafficking is a reality, and the blue background behind the blackened head asserts that this is a global reality. Some people are just barcodes, and the barcode on this subject is a blindfold.

The 2015 movie Spotlight directed by Tom McCarthy is about another kind of blindfold: the cover-up of the sexual abuse of young people and children by priests and church leaders. Spotlight focuses on cases in the USA, but these horrendous behaviors—the abuse and the cover-up—are global realities. Adults too are sexually abused in church premises, under the shadows of the cross and the eyes of the bible, and some of those are also covered-up (or blindfolded), but Spotlight’s focus is on the more vulnerable parishioners who are pushed into the blind spots of church leaders and church records.

This collection of essays discusses some of the cases of abuse and violence at the blind spots of the bible, and it works against the use of the bible to cover-up abuse and violence in society (in other words, the use of the bible to blind devotees and critics). There are four assumptions that, in different combinations and grades, the contributors to this collection share: first, the bible has blind spots; second, the bible is blinding; third, the bible is used to blind victims and critics; fourth, the bible can (be used to) expose blind spots and heal blindness. These assumptions play out in the following essays, divided into three overlapping sections—one focusing on dispersion, one dealing with othering practices, and one imaging a space where the dispersed and othered might re-gather and celebrate.

Flows of the Book

The intersections (or, inter- and ex-changes) of dispersion with othering—dispersed subjects are othered, and othered subjects are dispersed (at least emotionally dispersed if not physically dispersed as well)—make the division of the essays into three sections fraud. That said, we also add that the experience of dispersion and othering proves that division in itself is fraud. Dispersion and othering violate divisions and limits. Mindful of this conundrum, this collection comes upon the assumption that divisions and limits are fluid, and the voices that come through each essay seek to gather, to congregate, with the help of and in the eyes of readers who are not blind(ed) but who have both commitments and attitudes. Put directly, this work is for the eyes of readers who are also (interested in becoming) activists for and advocates of the dispersed and the othered in the bible and in society.

The division between the three sections is fluid, but there are themes and drives that flow and connect the voices in the essays. The essays in the first section—Trials of dispersion—flow from the dispersion of the builders of the Tower of Babel and the struggles of the indigenous people in Australia (Laura Griffin) to the ground level of Latin American Liberation Theology from where comes a call for solidarity with the dispersed people of Palestine (Darío Barolín), to the call for affirming slaves as siblings (Chrisida Nithyakalyani Anandan), to the call for reconsidering of antagonism toward Egypt and most things Egyptian (Jione Havea), to the call for reconsidering the rejection of Samaritans that biblical and modern empires manufacture (Néstor Míguez), to the call for affirming the fluidity of sacred margins in Hebrews (Mothy Varky), and to the call for embracing the dispersed in Mark and in the Asian diaspora (Jin Young Choi). There are, of course, more to each of these essays, but this reductionist introduction is for the purpose of explaining the fluid limits between the essays and for easing the fraudness of the divide between the three sections.

In the second section—Politics of Othering—the flow is from the othering of foreigners and females (Monica Jyotsna Melanchthon) to the othering of Zuleika in the shadows of Joseph in Gen 39 (Sweety Helen Chukka), to the othering of Gomer in Hosea 2 and battered women in modern settings (Bethany Broadstock), to the othering of a woman in birth pangs in Rev 12 (Vaitusi Nofoaiga), to the othering of women who are not or cannot be mothers in 1 Tim 8 (Johnathan Jodamus), to the othered voice in Ps 4 as a threshold for gay communities (Brent Pelton).

The final section imagines Ruth as a “ceremony site” for dispersed and othered subjects to re-gather and celebrate (Ellie Elia and Jione Havea). This twisting introduction is for the purpose of explaining one of the ways in which the essays flow into each other (more detailed introduction to each essay follows).

Trials of Dispersion

Laura Griffin (chapter 2) sets the tone for this first section with a reading of the dispersion of humanity in Gen 11:1–9. This narrative tells of a united humanity—speaking a common language—attempting to construct a city with a tower to reach to the heavens, a building project that troubled Yhwh. Yhwh responds by confusing the language of the people and scattering them to distant lands, and the remaining half-built city/tower is named Babel.

This narrative is one of the iconic narratives in the Hebrew Bible. It has long captured the attention and imagination of artists, storytellers and communities. Griffin’s essay offers an exegetical analysis of this pericope, building upon a brief outline of historical and literary frames for understanding the text. Griffin then propagates views that run counter to dominant theological commentaries, and invites rereading this narrative in “stolen lands,” such as the one that has come to be called Australia. The critical drive of this essay is for readers who live on stolen lands (and who doesn’t?) to reconsider their readings of the bible’s blinding spots.

Darío Barolín (chapter 3) wrestles with the words of Atahualpa Yupanqui (1908–1992), an indigenous poet and musician from Argentina who wrote a song titled Little questions about God. The song ends with these lines:

Barolín’s response to the song is in three questions: Is God [still] at the boss’s table? What or who put God at the boss’s table? How might we move God from the boss’s table? Barolín reflects on these questions from his Latin American context, in solidarity with the struggles of the dispersed people of modern Palestine, around the topics of oppression, liberation, exodus, the chosen ones, the native people of the land, the failures of liberation criticism, and the ongoing tasks for biblical interpreters.

Chrisida Nithyakalyani Anandan (chapter 4) analyzes the manumission of the slaves in Deut 15:12–18, drawing upon social identity theory, to determine whether group dynamics and group identity formation played a role in segregating masters from slaves. In the case of debt slavery, people who could not pay their debt become laborers to their neighbors (who are from the same group); this raises critical questions: Should their identity change when their circumstances change? Are they neighbors, laborers or slaves? Do they become neighbors again after they repay their debts? How did these differing identities influence or affect these pe...