eBook - ePub

Neoliberalism on the Ground

Architecture and Transformation from the 1960s to the Present

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Neoliberalism on the Ground

Architecture and Transformation from the 1960s to the Present

About this book

Architecture and urbanism have contributed to one of the most sweeping transformations of our times. Over the past four decades, neoliberalism has been not only a dominant paradigm in politics but a process of bricks and mortar in everyday life. Rather than to ask what a neoliberal architecture looks like, or how architecture represents neoliberalism, this volume examines the multivalent role of architecture and urbanism in geographically variable yet interconnected processes of neoliberal transformation across scales—from China, Turkey, South Africa, Argentina, Mexico, the United States, Britain, Sweden, and Czechoslovakia. Analyzing how buildings and urban projects in different regions since the 1960s have served in the implementation of concrete policies such as privatization, fiscal reform, deregulation, state restructuring, and the expansion of free trade, contributors reveal neoliberalism as a process marked by historical contingency. Neoliberalism on the Ground fundamentally reframes accepted narratives of both neoliberalism and postmodernism by demonstrating how architecture has articulated changing relationships between state, society, and economy since the 1960s.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Neoliberalism on the Ground by Kenny Cupers, Helena Mattsson, Catharina Gabrielsson, Kenny Cupers,Catharina Gabrielsson,Helena Mattsson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

History of ArchitecturePART 1

SHIFTING OBJECTS AND REPRESENTATIONS

1

PALACE ON MORTGAGE

THE COLLAPSE OF A SOCIAL HOUSING MONUMENT IN FRANCE

SIMILAR TO OTHER INDUSTRIALIZED COUNTRIES in the Global North benefiting from Keynesian welfare state policies, France underwent a radical change from centralized interventionism (dirigisme) to neoliberal market adjustments over the course of the 1970s.1 This change affected housing policies and production alike, and it reinforced existing fracture lines of social, ethnic, and urban segregation. In this chapter I look into the way housing and architecture as concrete material and symbolic practices participated in this change, and, within this investigation, I frame architecture as a process that unfolds within temporary urban constellations and political-economic shifts.

The case study of my investigation is the colossally inflated project Les Espaces d’Abraxas, in the Parisian new town of Marne-la-Vallée, planned and realized by the Catalan architecture firm Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura between 1978 and 1983 (plate 1). The three-part complex consists of some six hundred apartments, and its eighteen-story silhouette, with its eclectic pillared façade of precast concrete panels, towers like a symbolic city gate above its suburban surroundings. Because of its expressive formal language, Abraxas is considered a canonical example of postmodern architecture, which many philosophers, geographers, and cultural practitioners at the time declared to be a paradigm of reactionary social change.2 Since Abraxas is also an exemplary case of the consequences of the debt crisis that ensued after the neoliberal reforms of 1977, it can indeed serve as a paradigm of post-Fordist conditions of production, particularly regarding the disjunction between its aesthetics, its material production, and financing.3 On the other hand, both the materialization and the media representation of Abraxas include intentions and procedures that emerge from a logic of Fordist production, centralized interventionism, and a welfare state policy of social redistribution—intellectual, political, and economic. The sociopolitical background to the spectacular downfall of this project unveils the complex imbrication of neoliberal restructuring processes and the demise of the welfare state. In what follows, I frame this history—as the first main aspect of this chapter—through the lens of personal narratives, based on interviews with Abraxas residents conducted during my six-month stay in the building in 2012. In a first step, I investigate the constellation of Abraxas in the early 1980s; in a second step, I reconstruct the political and conceptual background of France’s neoliberal housing reforms of 1977 through a close reading of the eighth lecture of Foucault’s Birth of Biopolitics. Finally, I show the consequences and effects of these reforms on the French urban landscape in general and on Abraxas in particular. Here, I develop the second main aspect of this chapter, which consists in conceptualizing “architecture” as a constellation of disparate instances and which I illustrate by referencing the speed of the downfall of this housing monument and the radical disjunctions of its representations.

The Golden Age

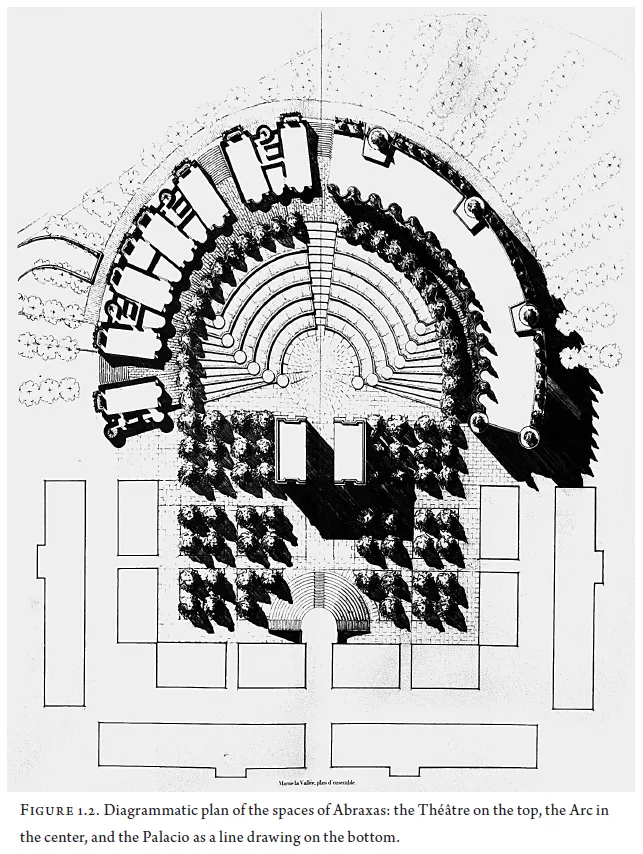

Due to its spectacular, stage-like setting, with labyrinthine access balconies and colossal canyons, Abraxas appears to be an exception both to large-scale modernist housing of the postwar boom years and to its postmodernist revisions. Morphologically, the axisymmetric complex consists of three building parts. The spatial distribution of the eighteen-story high-rise Palacio d’Abraxas is structured by a complex set of stairs and access balconies, with four elevator shafts contained in gigantic concrete columns featuring classical flutings on the exterior façades. The other two building parts are somewhat less extravagant by themselves but form a uniquely sculpted urban space. The nine-story Arc, in the center of the complex, resembles an inhabited triumphal arc whereas the semicircular Théâtre, toward the western part of the ensemble, overlooks a set of circular terraces like an amphitheater. These exceptional housing typologies can be related to the two main archetypes of modern surveillance architecture, namely the piranesian prison and the Panopticon. It is not an arbitrary coincidence that Abraxas served as the filming location for two globally distributed science-fiction movies that depict the terror of an authoritarian surveillance state: Brazil (directed by Terry Gilliam, 1985) and, thirty years later, the fourth film of the Hunger Games series (2015). During the last two decades, for Abraxas visitors whose mind-set is likely to be influenced by the narratives of the dangerous neighborhoods of the French banlieue, the leaps in scale and the mannerist monumentality of the building evoke almost reflexive associations with the uncanny, state authority, and surveillance.4

At the time of the project’s completion, however, the residents certainly did not perceive the unique scenery of the complex as a demonstration of state authority; they saw it as alluding to the appropriation of symbolic power by average citizens—the intention was “to exalt the life of its inhabitants,” as Ricardo Bofill put it.5 Abraxas was to be not just a building but an urban performance of a unique experience. The electroacoustic sound and light installation planned by the artist Pierre Mariétan, aiming at a complete staging of Abraxas—a project that was set aside due to lack of financing—is more than a footnote in its history.6 Regarding the architectural concepts embraced in Ricardo Bofill’s Taller de Arquitectura office, the approach to housing in terms of urban experience dates back to the mid-1960s, informed by the massive tourist urbanization of the Spanish coasts and developed in line with Bofill’s interest in film directing.7 At the end of the 1970s, film production design and ephemeral architectures were also an essential reference point for the Strada Novissima of the first Venice Architecture Biennale, where Abraxas was selected as one of the twenty exhibition façades. Back then, the curator of the biennale, as well as all members of its advisory board—Paolo Portoghesi, Christian Norberg-Schulz, Charles Jencks, and Vincent Scully—were enthusiastic advocates of Bofill. Charles Jencks even elevated the Catalan architect to the status of the “Bobby Fisher of architecture, the Muhammad Ali of architecture” and declared Abraxas to be a forceful alternative to modernist housing.8 According to Jencks, it was the only convincing representative of French classicism—and “why not, in the Age of Mitterrand (as luck would have it) give the people what every other class has sometimes obtained?”9 In the early 1980s, the French media experienced a similar enthusiasm. Headlines during that decade included “The Bofill Revolution,” “Bofill Superstar,” “Like the Romans . . . ,” “In the theater . . . every day, with Bofill.”10

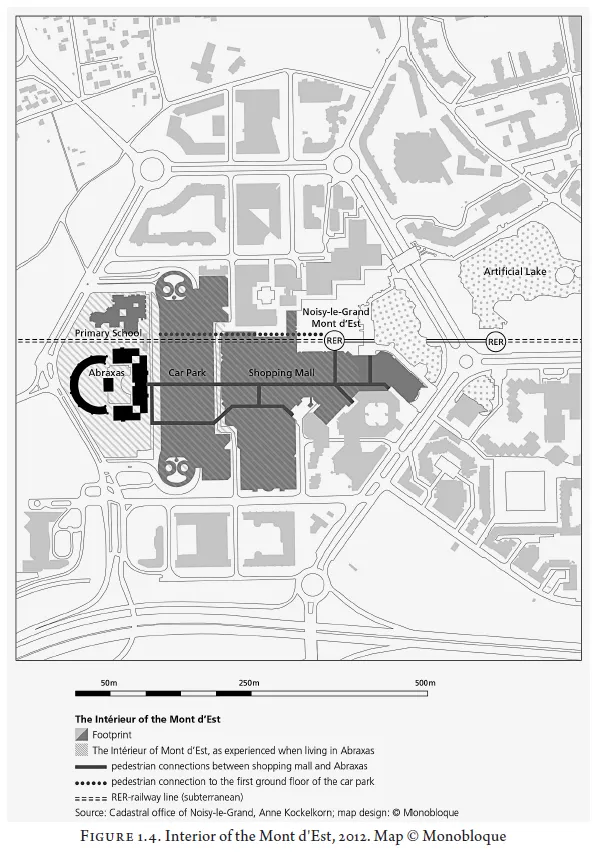

If the housing monument as a media spectacle seems to be a perfect fit for architectural narratives of postmodernism, the geographic location of Abraxas between the parking area of a regional mall and a highway feeder road tells a somewhat different story. The designation of the hillside plot of Abraxas and its plans for high-rise living can be traced back to the paradigms of the Parisian new towns of the mid-1960s and early 1970s, in which the urban model of dense, multistory housing in immediate proximity to public facilities and shopping was intended to provide for a high-quality living environment.11 This is still tangible in the everyday life of the complex. In the immediate neighborhood of Abraxas (the Mont d’Est), the monofunctional residential tower block gives residents a home in the midst of a regional center, with a shopping center and cinema as well as access to highways and the RER public transit system. The monumentality of Abraxas, its height, and its symmetry actually originate from the design brief of the new town planners, who intended to mark the centrality of the Parisian new town of Marne-la-Vallée with a high-rise building.12 Regarding housing tenure, Abraxas was originally a notable example of social and cultural diversity, from home owners who were senior executives to tenants who worked as domestic help, from families who had lived in the Paris region over several generations to those who had arrived as refugees from the former colonies of Indochina. That diversity also corresponded to the housing policies of the mid-1970s and an official narrative that aimed to promote the housing market by underscoring flexibility and choice. On the one hand, the aim of diversity supported the need to place low-income groups in French social housing estates to which they previously had not had access. “High cost” and “segregation” were seen on the other hand as a problem of the public financing of social housing and the public procurement of particular housing types.13 If a third of the units of Abraxas were marketed as private property and the remainder rented as social housing, this mix is not only in line with public policies but also a normal occurrence among the “experimental realizations” of French housing production of the late 1970s.14 At the same time, the social fracture lines in Abraxas did not occur between owners and renters but rather according to the various administrative procedures and lending instruments used to place residents in the building.15

Socially disadvantaged owners and tenants represented the minority of residents. For them, moving into Abraxas was often perceived as a remarkable social advancement. In familiarizing themselves with the building and its neighborhood they were curious and happy to discover celebrities, artists, actors, or doctors as their neighbors, as people who could be met in the elevator. In the imaginary of some residents, such persons included even the architect himself—and indeed, in April 1982, Ricardo Bofill briefly considered buying a triplex apartment in the Palacio.16

The interweaving of aesthetics and the political economy marks the conception of Abraxas, which was developed at a time when political support for individual home ownership reached a peak in the housing history of France. “Do you sell the Palaciò like a work of art?” the French architectural magazine Techniques et Architecture asked the director of the housing company CNH 2000 in 1982. “Absolutely! Like a truly singular artwork,” he replied.17 Abraxas was to serve both as a work of art in architectural discussions and as a commodity on the French housing market; Ricardo Bofill, the town planners of Marne-la-Vallée, and the housing developer CNH 2000 all shared a consensus on bringing postmodern strategies of representation in line with welfare state policies undergoing a process of neoliberal restructuring.

But the high hopes implicit in bestowing social housing with a new and spectacular shape, one that catered to the lifestyles of the middle and upper classes, were not fulfilled. In less than fifteen years, Abraxas changed from a proud showcase project of the Parisian new towns to a site of social and urban problems. At the time of my two stays in the building complex, in 2011 and 2012, it was considered a problem area in the municipality of Noisy-le-Grand, and an unauthorized request for partial demolition submitted to the Agence Nationale de Rénovation Urbaine (ANRU) lay in the files of the municipal administration. At this moment, the idea of Abraxas as an attractive living environment for a well-off, up-and-coming middle class was unthinkable.

Introduced by the urban anthropologist Alessia de Biase, the notion of a golden age of modernist housing estates captures the amazement and satisfaction of residents experiencing the comfort of modernization for the first time: running water, central heating, modern appliances, and, not least, space and light.18 What they didn’t encounter, however, was the experience of the city; and, after factory closings in the 1970s, the golden age of many modernist housing estates didn’t last longer than a couple of years. Emerging from the context of French new town planning, which was intended to counter all the deficiencies of postwar modernization—especially monotony and territorial isolation—Abraxas was realized after the economic crisis of the 1970s had already gained a foothold. If the aim of the building...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Undead Neoliberalisms

- Part 1. Shifting Objects and Representations

- Part 2. Policies and Spatial Production

- Part 3. Professional Practices in Transformation

- Part 4. Subjectivities in Formation

- Epilogue: Neoliberalism and Architecture, Backward

- Contributors

- Illustration Credits

- Index