- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In 1949 construction of the planned town of Nowa Huta began on the outskirts of Krakow, Poland. Its centerpiece, the Lenin Steelworks, promised a secure future for workers and their families. By the 1980s, however, the rise of the Solidarity movement and the ensuing shock therapy program of the early 1990s rapidly transitioned the country from socialism to a market-based economy, and like many industrial cities around the world Nowa Huta fell on hard times.

Kinga Pozniak shows how the remarkable political, economic, and social upheavals since the end of the Second World War have profoundly shaped the historical memory of these events in the minds of the people who lived through them. Through extensive interviews, she finds three distinct, generationally based framings of the past. Those who built the town recall the might of local industry and plentiful jobs. The following generation experienced the uprisings of the 1980s and remembers the repression and dysfunction of the socialist system and their resistance to it. Today's generation has no direct experience with either socialism or Solidarity, yet as residents of Nowa Huta they suffer the stigma of lower-class stereotyping and marginalization from other Poles.

Pozniak examines the factors that lead to the rewriting of history and the formation of memory, and the use of history to sustain current political and economic agendas. She finds that despite attempts to create a single, hegemonic vision of the past and a path for the future, these discourses are always contested—a dynamic that, for the residents of Nowa Huta, allows them to adapt as their personal experience tells them.

Kinga Pozniak shows how the remarkable political, economic, and social upheavals since the end of the Second World War have profoundly shaped the historical memory of these events in the minds of the people who lived through them. Through extensive interviews, she finds three distinct, generationally based framings of the past. Those who built the town recall the might of local industry and plentiful jobs. The following generation experienced the uprisings of the 1980s and remembers the repression and dysfunction of the socialist system and their resistance to it. Today's generation has no direct experience with either socialism or Solidarity, yet as residents of Nowa Huta they suffer the stigma of lower-class stereotyping and marginalization from other Poles.

Pozniak examines the factors that lead to the rewriting of history and the formation of memory, and the use of history to sustain current political and economic agendas. She finds that despite attempts to create a single, hegemonic vision of the past and a path for the future, these discourses are always contested—a dynamic that, for the residents of Nowa Huta, allows them to adapt as their personal experience tells them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nowa Huta by Kinga Pozniak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Eastern European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Memory and Change in Nowa Huta’s Cityscape

The city itself is the collective memory of its people.

—Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City

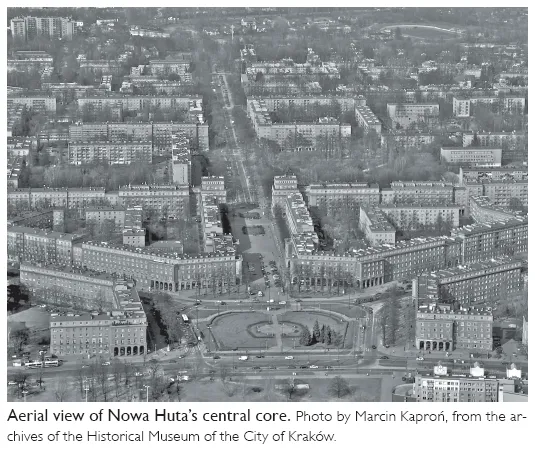

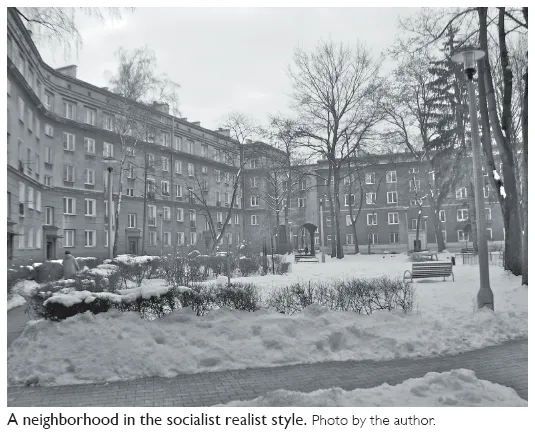

If you and I arrive in Kraków and ask for directions to Nowa Huta, we will be told to take the streetcar to Central Square (Plac Centralny) and get off there. The square is actually more of a transportation circle where five streets converge. If we stand in the very center, in the small green area surrounded by streetcar tracks, we can see many defining features of Nowa Huta that speak to different aspects of the district’s history. The square is surrounded by buildings in the socialist realist style, although the tourist could be forgiven for confusing it with Renaissance style, for the buildings’ defining features are arches and columns. These buildings used to house some of the nicest stores in Nowa Huta, including the popular fashion boutique Moda Polska (literally “Polish Fashion”) and the popular bookstore chain Empik. Neither one is here anymore, and instead the store space is taken up by banks, a cell phone store, a grocery store, a flower shop, another bookstore, a German drug store chain, and a liquor store that is open around the clock. The top floors of the buildings are residential. In front of the storefronts stand a few kiosks selling newspapers and cigarettes, as well as a few pretzel stands, whose wares are hungrily snatched up by passersby rushing to and from work.

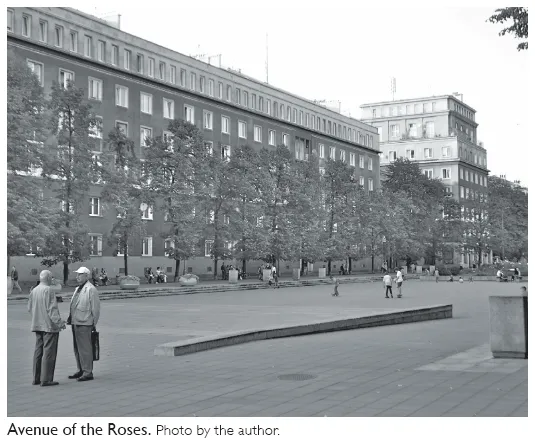

From here, we can travel in several directions. To the north lies a square where a statue of Lenin used to stand. This is where May 1st parades1 would take place under the watchful eye of the leader of the Russian revolution. The square was renovated after Lenin’s eviction from Nowa Huta and is now a favorite location among skateboarders. The sound of their skateboards hitting the concrete echoes throughout the square, much to the chagrin of the residents of surrounding buildings who complain about the noise. The square is lined with benches, which on warmer days are occupied by seniors and parents or grandparents watching over small children who use the square for their first biking or rollerblading lessons. An ice cream stand under one of the archways tempts passersby with what is reportedly the best ice cream in Nowa Huta. The buildings surrounding the square house a milk bar and the town’s legendary restaurant Stylowa, both of which we would have visited if we had gone on the communist tour described in the introduction. There is also a dubious-quality pub, a bakery and pastry shop, yet another flower shop, and a photographer’s studio.

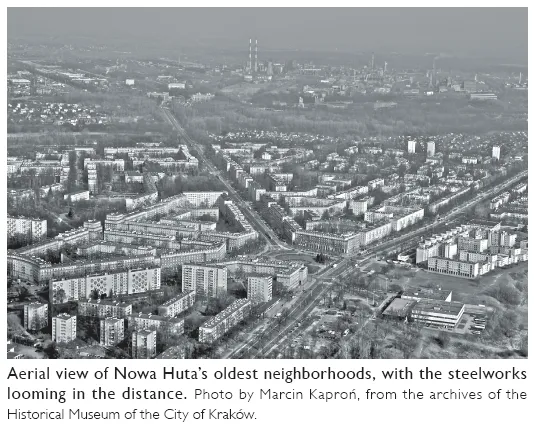

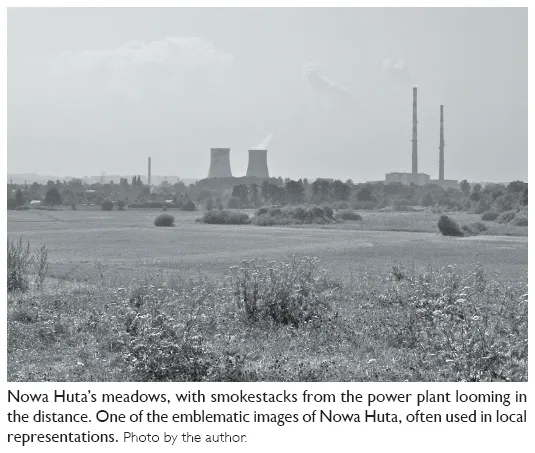

If we return to Central Square and look south, in the exact opposite direction, we will see Nowa Huta’s meadow, stretching out over an area of approximately half a square kilometer. This wetland is home to many bird and flower species and is now a protected area. Locals use the newly built path across the fields for strolling or walking their dogs. On hot summer days one can always spot several sun enthusiasts sprawled out on blankets. Far in the distance, beyond the meadow, we can see two fat smokestacks and two skinny ones—that is the power plant on the border area between Nowa Huta and Kraków, in a neighborhood called Łęg. The juxtaposition of green space with chimney stacks is quite striking and is used in many local representations of Nowa Huta.

If we stand in the middle of Central Square once again and look down the road leading northwest, far in the distance we will see what looks like a castle perched on top of a gentle hill. From here we can just barely see buildings with crenellated roofs, reminiscent of the Doges’ Palace in Venice. That is not a palace, however—it is the administrative center and the entrance to the steelworks. We will go inside the gates in the next chapter. Right now, our focus is on the town itself.

Nowa Huta (literally New Steelworks) is a district of the city of Kraków constituting approximately a third of its surface area and population. At present, its population stands at approximately 220,000 people. Originally built in 1949 as a separate town, in 1951 Nowa Huta became incorporated into the city of Kraków as one of its administrative districts. However, it has always maintained a very distinct identity from the rest of the city.

The history of Nowa Huta can be seen in many ways as the history of postwar Poland “in a nutshell” (Stenning 2008). It was originally built by the postwar socialist government and intended to be the country’s flagship socialist town that would embody the processes of industrialization, urbanization, and the creation of a new working class—the basic tenets of postwar socialist philosophy. Ironically, over time Nowa Huta also became an important site of dissent to the socialist government. After that government’s collapse, Nowa Huta became transformed by the processes of economic restructuring, deindustrialization, and globalization.

This chapter begins with an outline of Nowa Huta’s history from its construction to the present. The events and phenomena described here will be referred to throughout the book, for they recur in people’s stories and in the district’s public representations. I then examine how this history is reflected, negotiated, obliterated, or rewritten in the cityscape as Nowa Huta tries to reinvent its image and economy in the changed political and economic order.

A Model Socialist Town

The history of the town of Nowa Huta begins in the period immediately following World War II, when Poland became governed by a socialist party backed by the Soviet Union. Socialist ideology emphasized industrialization and urbanization as vehicles to growth, modernization, and progress. Consequently, across the Soviet Bloc, new industrial sites and projects were being built along with new towns that were to house their workforce. Almost every Soviet Bloc country had its flagship town that was to embody socialist principles in urban planning, economic development, and social organization (Aman 1992). In Poland, this model socialist town was Nowa Huta.2

The decision to build a new steelworks in Poland was made on May 17, 1947, and was the cornerstone of the socialist government’s economic plan (termed the Six-Year Plan) for the years 1950–56. At the time, Poland’s political and economic policy was heavily influenced by the Soviet Union under Stalin’s reign, and the Six-Year Plan reflected the Soviet Stalinist-era emphasis on the development of heavy industry. Two years later, it was determined that the country’s new flagship industrial project would be built on the outskirts of Kraków. Along with a new steelworks, a new town was to be built to house its workforce, the new socialist working class. Building Nowa Huta was thus “synonymous with building socialism itself” (Lebow 1999, 167).

The construction of the town’s first residential buildings began in 1949, the construction of the steelworks a year later. The labor power was recruited from all over Poland, composed of predominantly young work migrants who sought work in the growing town in the light of the postwar poverty in Poland’s countryside, as well as mandatory youth labor brigades called Service to Poland (Służba Polsce). Service to Poland was a national organization intended to provide youth between sixteen and twenty-one years of age with work-related training, military training, and physical education, and to inculcate in them a socialist political and ideological consciousness (Lebow 2013; Lesiakowski 2008). As the country’s model socialist town, Nowa Huta became the organization’s flagship assignment. As Katherine Lebow writes, building Nowa Huta was depicted as a “pedagogical project—both in the practical sense (as a kind of giant vocational school offering training for all) and also, more abstractly, as a site of personal formation and transformation” (2013, 54). And finally, newcomers to Nowa Huta also included former Home Army (Armia Krajowa, or AK) soldiers who could more easily lose themselves in the hustle and bustle of a new town to avoid persecution;3 a sizeable Roma minority, forcibly settled by the government in urban areas; and a small number of Greek refugees, fleeing civil war at home (Miezian 2004). Although work on the town’s construction was physically demanding and characterized by very high turnover, about one-third of the people who came to Nowa Huta in the late 1940s and 1950s ended up settling there for good (Lebow 2013).

It is well documented that states often govern through the ordering of spaces, as well as people and objects within spaces (see, e.g., Hall 1996; Rabinow 1989; Scott 1998). This tendency is particularly visible in twentieth-century modernist thought, which considered architecture and urban planning to be instruments of social change (Holston 1989). Many of the ideas and principles developed by modernist architects and urban planners were adopted in Soviet Bloc countries, where the physical transformation of space was an important element of the socialist project, aimed at creating a new form of society (Crowley and Reid 2002; Czepczyński 2008; Nawratek 2005). Geographer Mariusz Czepczyński argues that socialist ideology was characterized by a “strong structuralist belief that social and living conditions create the individual, his or her personality and value system” (2008, 67). Socialist leaders believed that “new ways of organizing the home, the workplace or the street would . . . produce new social relations that would, in turn, produce a new consciousness” (Crowley and Reid 2002, 15). The socialist architect and urban planner thus became an “engineer of the human soul” (Czepczyński 2010).

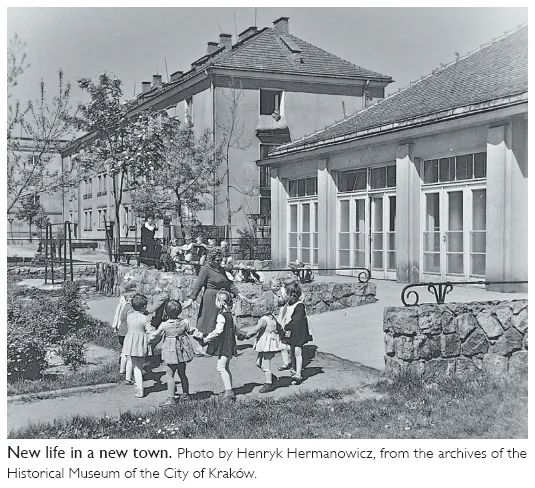

Urbanization was one of the key tenets of the socialist government’s project of building a new society. Consequently, many elements of the urban landscape took on a political significance (Czepczyński 2010, 19). Nowa Huta epitomizes this tendency on the part of the socialist state to try to forge a new political, economic, and social order through the organization of space. The town’s very name (New Steelworks) signifies its role as Poland’s first socialist town, home to the first large steelworks in the country, named after Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin. Many Nowa Huta streets and neighborhoods were also given names that depicted what was intended to be the new reality. For example, two of Nowa Huta’s neighborhoods were called “Steel” and “Youth,” and street names commemorated socialist heroes Lenin and Marx; Polish communist activists such as Julian Leński and Władysław Kniewski; and events such as the October Revolution, the Six-Year Plan, and Polish-Russian friendship. Poems and songs praised the growing town; for example, Polish poet (and later Nobel prize winner) Wisława Szymborska referred to Nowa Huta in one of her poems as the “town of good fortune” (miasto dobrego losu). School textbooks hailed Nowa Huta as a symbol of “fighting for socialism” and “fighting for the 6-year plan” (Samsonowska 2002). Movies, songs, and poems evoked images of happy shirtless bricklayers from the Service to Poland brigade singing at work, new buildings springing up, and smiling children playing in new playgrounds. In all, Nowa Huta was depicted as a town of youth and opportunity, a place where young people from all over the country came to escape the supposed “backwardness” and “misery” of peasant life to work, get an education, start families, and build their lives.

The design of Nowa Huta’s urban plan and architecture was inspired by elements of modernist urban planning, adapted to socialist ideology and to the Polish context in particular. The town’s urban layout was designed by architect Tadeusz Ptaszycki, who combined certain Soviet solutions with modernist and utopian ideas from outside of the Soviet Bloc. For example, the design of Nowa Huta’s urban core, with streets radiating at a forty-five-degree angle from the center, was inspired by the prevailing Soviet trends in urban design at the time. Also modeled on Soviet urban planning were large precincts, closed off from main streets (Aman 1992). On the other hand, a number of Nowa Huta’s design ideas were imported from outside of the Soviet Bloc. One such concept was the neighborhood unit, initially developed in New York City in the early 1900s (Perry 1974). According to this design principle, the town is divided into neighborhoods. Each neighborhood consists of a cluster of buildings, which, taken together, house between four and five thousand people. Each neighborhood contains all the basic infrastructure and services necessary for the everyday functioning of its residents, including a school, a day care, and a grocery store (Miezian 2004; Juchnowicz 2005). To this day, the neighborhood serves as a topographical reference point for Nowa Huta residents. When people are asked where they live, they give the name of their neighborhood instead of a street intersection, and Nowa Huta postal addresses contain no street names, making it initially confusing to navigate for anyone not familiar with the district.

When I asked Nowa Huta residents what they like about their district, many people mentioned the urban design. This is noteworthy, because centrally planned neighborhoods of the socialist era now have a bad reputation in Poland: they are popularly seen as ugly, poorly constructed, and decaying. However, many Nowa Huta residents praise the proximity and availability of all essential infrastructure and services, which they favourably compare with recent trends in real estate development. Mr. Pawłowski,4 a retired steelworker in his eighties, told me: “There are some beautiful new buildings being built around Nowa Huta. But you see how they are squeezed together; developers don’t care if people have any green space at all, or if they won’t have a store close by to get milk. So you see, there is a difference in the way of thinking between the new, good leaders and the old, evil [wredne] ones.” (The words “good” and “evil” were said in an ironic tone.)

In these words, Mr. Pawłowski praised the aesthetics of contemporary real estate but critiqued the way commercial interests trump the public ones. Socialist-era central planning, he suggested, was comprehensive and intended to provide the residents with a good quality of life, whereas contemporary real estate development is piecemeal and driven solely by developers’ quest for profit. His comments were echoed by many Nowa Huta residents. Many seniors positively remarked on the walking-distance accessibility of grocery stores and pharmacies. A few mothers commented that the layout of the neighborhoods, with a courtyard surrounded on all sides by buildings, made it possible for children to play outside by themselves, since they were less likely to run out onto a busy street.

Another principle that underpinned Nowa Huta’s construction was the “Garden City” concept, modeled on the utopian ideas of Ebenezer Howard (1966). Garden Cities were intended to be self-contained communities surrounded by greenbelts and containing proportionate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture. These principles subsequently influenced the construction of many towns in Britain, the United States, Latin America, and elsewhere (Miezian 2004). Nowa Huta’s first architects were also inspired by this concept. They envisioned a spacious city with wide streets and numerous parks and playgrounds, as well as water elements such as fountains and a man-made pond. Notwithstanding the later environmental havoc wreaked on the town by the steel industry, many of these principles in fact survived the socialist period. To this day, Nowa Huta residents favorably compare the amount of green space in their district with the cramped streets of Kraków’s downtown core. The trees that were initially planted in the 1950s by socialist-era “volunteer labor brigades” (czyn społeczny) are now tall and majestic. (In fact, when I tried to take photos of Nowa Huta’s architecture I always found that the trees got in the way!) The district has several community gardens where residents cultivate flowers and sometimes vegetables and fruit trees. Many residents also grow flowers on small garden plots in front of their apartment buildings. The greenbelts between the streets and the apartment buildings are dotted with benches, which from March to November are occupied by seniors enjoying a chat or stopping for a few minutes’ rest on their way home with groceries.

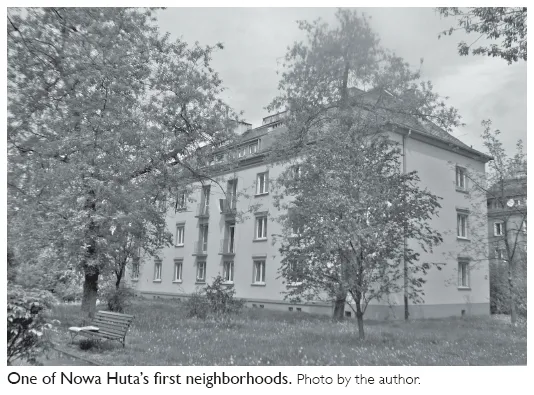

As Nowa Huta grew and expanded over the years, the design of successive neighborhoods reflected the country’s changing political ideologies and economic realities. Nowa Huta’s first neighborhoods, whose construction began even before the town’s urban plan was finalized, are characterized by two-story buildings with peaked roofs. This design is loosely based on nineteenth-century models of small-town planning. Subsequent neighborhoods, erected in the 1950s under the newly developed urban plan, are strongly influenced by socialist realism. Socialist realism was an artistic and architectural style developed in the Soviet Union and prevalent during the Stalinist period. It was marked by a preference for classical elements such as arches, pillars, and elaborate decorative elements, as well as a tendency toward monumentalism (for example, monuments or grandiose structures) (Aman 1992). Socialist realism was to be socialist in content and national in form, meaning that each Soviet Bloc state looked to its own national tradition for design inspiration. In Nowa Huta, socialist realism took on a particular national form through the incorporation of Renaissance and Baroque elements inspired by the architecture of Kraków’s oldest core (for example, arches, pillars, balustrades, window pediments, and portals). This trend can be seen most clearly in the design of Nowa Huta’s Central Square and the administrative center of the steelworks.

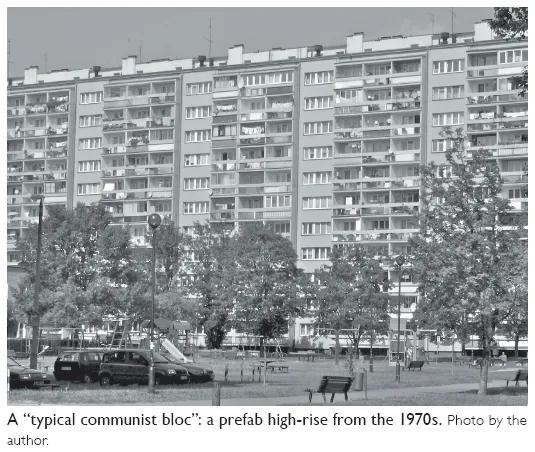

Following the “thaw” of the mid-1950s, socialist realism was abandoned in favor of modernist solutions. The “thaw” (also known as the “little stabilization”) refers to the period following Stalin’s 1953 death. It was characterized by some political reforms, some lessening of censorship, and greater independence from the Soviet Union. From that point on, buildings lost all their ornamentality and were constructed using much cheaper precast concrete. The 1970s were characterized by the construction of the prefabricated high-rises so often associated wit...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Memory and Change in Nowa Huta’s Cityscape

- Chapter 2. From Lenin to Mittal: Work, Memory, and Change in Nowa Huta’s Steelworks

- Chapter 3. Between a Model Socialist Town and a Bastion of Resistance: Representations of the Past in Museums and Commemorations

- Chapter 4. Socialism’s Builders and Destroyers: Memories of Socialism among Nowa Huta Residents

- Chapter 5. My Grandpa Built This Town: Memory and Identity among Nowa Huta’s Younger Generation

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index