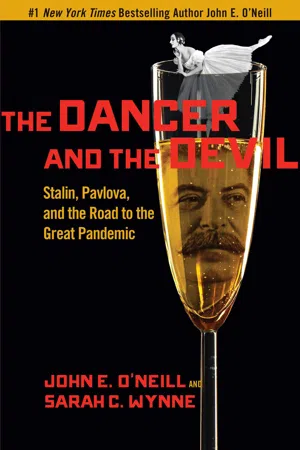

CHAPTER ONE Pavlova’s Candle in the Wind

The Dying Swan

The Dying Swan is a four-minute solo dance which was choreographed by the great Russian dancer Mikhail Fokine with one ballerina in mind. That dancer was Anna Pavlova, still widely regarded as the greatest of all ballerinas, who performed The Dying Swan over four thousand times, from Paris to New York, from Mexico to Australia.

Grainy film from the silent era gives us a glimpse of Anna Pavlova on stage. As the swan, Pavlova raises her tremulous arms and gazes upward, as if begging the heavens for her life. Her arms wave and flutter, only for her to be pulled, time and again, to the ground by her failing body. A contemporary French critic wrote, “faltering with irregular steps toward the edge of the stage—leg bones quiver like the strings of a harp—by one swift forward-gliding motion of the right foot to earth, she sinks on the left knee—the aerial creature struggling against earthly bonds; and there, transfixed by pain, she dies.”1

The Dying Swan touches the thin line between life and death, between the spiritual and the physical. It is to some a tragic funeral dance of death, to others a dance at the gate to resurrection. For Anna Pavlova, Fokine, and other Russian exiles, it became a way to memorialize the life they had known in their Russia, before the Bolshevik Revolution. By 1930, the performance had also become for these expatriates a way of grieving for a homeland in which so many friends, so many artists, and so many faceless millions were being shot or starved to death by the regime of Joseph Stalin.

It was also an act of resistance, both to commemorate those dead and to carry on the culture of the old Russia that Stalin labored to destroy at home and abroad. Anna and her coterie of Russian exiles knew that Stalin’s wrath did not end at the border. Around Europe, Russian artists, performers, and impresarios who had defied the regime by refusing summons to return to the Soviet Union were dying from mysterious causes. Healthy people, in the prime of their lives, were suddenly taking ill and dying within hours.

This book is more than a history of these exiled Russian artists and their persecution by Stalin. It is the examination of historical and current mysteries with the tools of the detective and an attorney’s eye for evidence that seals guilt. More than once, Anna Pavlova told her friends that a “sword of Damocles” hung over her head. Just before Christmas, 1930, an audience packed into the Golders Green Hippodrome in London to watch Pavlova perform The Dying Swan. Pavlova likely also danced her own great ballet composition Autumn Leaves set to the music of Chopin, describing a beautiful flower killed by the evil North Wind.

It was to be the last public dance by history’s greatest ballerina.2

The Mysterious Death of Anna Pavlova

Pavlova died in the early morning hours of January 23, 1931, at age forty-nine. Hers was the first of many deaths of great diva celebrities in the twentieth century—Jean Harlow, Marilyn Monroe, Lady Diana—spectacles that left the public both enchanted and grieving. Though largely forgotten in popular memory today, the death of Anna Pavlova shocked the world.

Her death, as Churchill’s description of Russia itself, was a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. Pavlova had been in Paris for several days rehearsing for her 1931 tour of European countries and the United States.3 After taking lunch in her hotel room, Pavlova boarded a train for the Netherlands, where she was scheduled to appear at The Hague. She became ill soon after departure. She struggled to breathe, and her lungs began to fill with fluid.4 Once in her room at the Hotel Des Indes in The Hague, Pavlova sent for her personal physician from Paris, who joined the Dutch physicians who hovered over her.5 Although she told the doctors and her husband, Victor D’André, that she had been “poisoned” by the food in Paris, no one took her words seriously.6 Instead, her doctors treated her for pneumonia. When that failed, they treated her for bacterial blood poisoning.7 As the doctors failed to find a cause, they were reduced to treating symptoms. Despite their efforts, injecting her with serum and draining fluid from her lungs, nothing they did helped.8 With death closing in, Anna Pavlova made her company swear to go forward with the scheduled opening performance of her tour on the following night. Around midnight, she called for the costume that she had worn so many times as the dying swan.9 Too weak to speak further, she raised her hand as if making the sign of the cross, and died.

On the following night, true to her company’s promise and her command, the show went on before a weeping audience. Anna’s part was played by no one; a spotlight followed her marks on the stage. And when Anna’s signature Dying Swan was played with the spotlight shining where she should have stood, the audience, led by the king and queen of Belgium, was moved to tears. Royals and commoners stood as one, openly crying.

The death of Anna Pavlova was front-page news all over the world—except in the Soviet Union, which earnestly ignored the fact that the most famous daughter of Russia had just died. Her sudden death was mysterious enough to provoke a Dutch police investigation, which yielded nothing except the clearing of her husband who had been in London when she first became ill.10 The fact that such an alibi was required for Victor D’André demonstrates that the Dutch detectives believed there was reason to suspect Pavlova’s death was a homicide. Various unlikely causes for her death were proposed. She had stood briefly in the rain a few days before her death. Perhaps that had caused an unknown respiratory ailment? Her death was ultimately ascribed to pleurisy. That she suffered from inflammation of the lungs was certain. But these were fatal symptoms without a certain cause. As recently as 1996, the Dutch surrealist artist and writer Jean Thomassen dealt with Pavlova’s mysterious death, concluding it could not have been pneumonia and instead ascribing the death to contaminated surgical instruments which caused blood poisoning.11

Pavlova’s London mansion, Ivy House, and her costumes were auctioned off to the highest bidder. Famous for populating her estate’s lake with swans, Anna had a favorite: her devoted swan Jack who loved Anna, fiercely guarded her, and was often photographed with her at Ivy House. He disappeared after Anna’s death. Anna passed into legend, the subject of a biography by the great ballerina Margot Fonteyn and an inspiration to a legion of little girls, including Audrey Hepburn.12 Homages to Anna Pavlova are many, such as “Fred’s Steps,” a ballet sequence created by Sir Frederick Ashton, head of the Royal Ballet, commemorating his inspiration in 1917 at age thirteen in Lima, where he saw Pavlova perform.13 From time to time, dancers and admirers of many nations find their way to Ivy House. They leave flowers and notes. Even now, nearly ninety years after her exit, the great, now legendary, Pavlova is invariably included in lists of history’s greatest dancers—usually at the top.

Ashes and Porcelain

The Golders Green Hippodrome, once advertised by a marquee gaudy with electric bulbs, is now a Protestant megachurch. Anna Pavlova is interred a five-minute walk away at the Golders Green Garden and Crematorium in the north of London. The twelve-acre Garden of Rest, which surrounds the crematorium, is among the most beautiful cemeteries in London, planted nearly one hundred years ago by the garden designer William Robinson. Designed primarily in a wild English cottage garden style, but with a Japanese garden pond and impressive monuments, it includes almost five hundred British dead from the First World War.

The ashes of many of England’s most famous entertainers also rest there, including writer H. G. Wells, actors Peter Sellers and Sir Cedric Hardwicke, and musician and drummer Keith Moon of The Who. Except for the rather dreary Communist Corner (reserved for leaders of Britain’s Communist Party), Golders Green is a lighter and happier place for internment than under a stepping stone in the dark shadows of Westminster Abbey.

On a shelf in a niche sits a marble urn containing the ashes of Anna Pavlova. It is marked only with her name in Russian and English and an inscription of the date of her death. In contrast to many pretentious statues like that of a dour Sigmund Freud, Pavlova’s urn is joined only by a beautiful porcelain swan protectively guarding her ashes and a porcelain ballerina representing a dancer at final rest. These simple objects were once accompanied by the ballet slippers in which she danced around the world, but these and much else were stolen long ago.

A visitor cannot help but feel a sadness tinged with rage over Pavlova’s ashes, the feeling of a great dance performance prematurely interrupted. Walk to Ivy House, where Pavlova established her ballet school and appeared in pictures worldwide with her pugnacious but protective swan Jack, and one will find a bronze statue depicting Pavlova as a ballerina en pointe, arms outstretched and looking up as if about to fly to a far different place than Golders Green.14

For decades, the Russian government sought the return of Pavlova’s ashes, as it had once pursued Pavlova herself in life and later, her estate.15 Recently a publication of the Russian government picturing Pavlova’s ashes described her as first among the most famous and greatest of Russians whose remains are still located outside of Russia.16 In 2000, Russian officials, joined by Dutch Pavlova fans, were within a few days of transporting her ashes to Moscow when Pavlova’s friends and relatives succeeded in blocking the transfer. Moscow was a city with little connection to Pavlova, who had danced with the long-gone Imperial Ballet in the once great Mariinsky Theater in Saint Petersburg, then the center of the ballet world.17

Pavlova’s friends and admirers in Hollywood, where she had visited and briefly starred in a silent film, mourned her mysterious death the following year on film. The Grand Hotel (1932) is centered around the story of a doomed Russian ballerina, clearly patterned after and inspired by Pavlova. Only the great Greta Garbo could play the ballerina, whose lover in the movie was Anna’s close personal friend John Barrymore. At the film’s end, the ballerina goes to the Vienna train to meet Barrymore, who, unbeknownst to her, has been murdered. She is clearly doomed as well, but her precise end in the movie is left a mystery, as in life. The Grand Hotel won the 1932 Academy Award for Best Picture, but no other awards—the only film ever to do so. Perhaps this recognition was the Academy’s way of underscoring unanswered questions. Like The Grand Hotel’s mystery, Pavlova’s friends and admirers insisted that her death was as much a mystery as a misfortune.

Destruction of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour

As Anna Pavlova was dying, Stalin was planning the destruction of the most renowned church in the Christian Orthodox world, Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Next to Pavlova, it was the clearest symbol to the world of Old Russia, and thus a threat to Stalin’s campaign to erase Russia’s historic culture and replace it with Soviet agitprop.18 Situated near the Kremlin with a vast golden dome visible throughout the city, the church was built to commemorate the salvation of Russia from Napoleon. It was designed in the style of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, the center of the Christian Orthodox world for a thousand years until its conquest by the Turks in 1453. The 1812 Overture by Tchaikovsky was first written and performed for the church’s completion. Through the hunger and grief of World War I and the trauma of the Bolshevik revolution, the great golden dome of the church on Moscow’s skyline reminded all of both another time and the promise of future redemption. A month after Anna died in The Hague in January 1931, the Soviet security organ, OPGG, planned for workers in Moscow to quickly remove the golden dome before demolishing the church.19 With this demolition, Stalin believed that even the memory of Old Russia and the hope for a future reversion to religion would disappear. Stalin was, of course, disastrously wrong. The church was rebuilt, almost identically, by the Russian Orthodox Church between 1995 and 2000.

There is no evidence that anyone outside Russia at the time connected the two events—the mysterious death of the world’s greatest ballerina in The Hague and the ensuing destruction of Russia’s greatest church in Moscow—even though they involved the loss of two of the most important symbols of historic Russia. To understand the how and why of Pavlova’s mysterious death, it is necessary to understand the connection between these events and what Pavlova’s life represented to Russia and the world. To solve the mystery of her premature death, it is necessary to understand the dark motives of the dictator Stalin.

The Great Cathedral was an obvious, even necessary, target for Stalin and his regime. It was visible from many windows in the Kremlin, that rambling, ancient collection of palaces and buildings built by the Romanov dynasty. In an office there in the ironically named “Palace of Amusement” sat the man who ordered the destruction of the Great Cathedral. Stalin also ordered destruction of Russia’s most famous historic structure, the so-called Gate of Resurrection topped by the Iberian Chapel, where Russians entering today’s Red Square had prayed for four hundred years. He had no need of a Gate of Resurrection since Stalin had decreed that he would kill God so completely that even the word “God” would be forgotten in Russia by 1937.20 In a century of carnage, Stalin would exceed Hitler and rival Mao as the century’s most successful killer, ordering the murder of tens of millions of human beings.

Stalin, wrecker of cathedrals, was perhaps the only person in the world who would have smiled at the death of the beloved ballerina. One of communism’s most prominent critics, George Orwell, would later capture the mentality of Stalin and his obsession with what could have been dismissed as mere “cultural” milestones and personalities: “Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.”

What sledgehammers and explosives did to a church that represented the past, poison did to Russian expatriates who had become inconvenient r...