- 239 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A look at what Native American life was like in the Bay Area before the arrival of Europeans.

Two hundred years ago, herds of elk and antelope dotted the hills of the San Francisco–Monterey Bay area. Grizzly bears lumbered down to the creeks to fish for silver salmon and steelhead trout. From vast marshlands geese, ducks, and other birds rose in thick clouds "with a sound like that of a hurricane." This land of "inexpressible fertility," as one early explorer described it, supported one of the densest Indian populations in all of North America.

One of the most ground-breaking and highly-acclaimed titles that Heyday has published, The Ohlone Way describes the culture of the Indian people who inhabited Bay Area prior to the arrival of Europeans. Recently included in the San Francisco Chronicle's Top 100 Western Non-Fiction list, The Ohlone Way has been described by critic Pat Holt as a "mini-classic."

Praise for The Ohlone Way

"[Margolin] has written thoroughly and sensitively of the Pre-Mission Indians in a North American land of plenty. Excellent, well-written." — American Anthropologist

"One of three books that brought me the most joy over the past year." — Alice Walker

"Margolin conveys the texture of daily life, birth, marriage, death, war, the arts, and rituals, and he also discusses the brief history of the Ohlones under the Spanish, Mexican, and American regimes . . . Margolin does not give way to romanticism or political harangues, and the illustrations have a gritty quality that is preferable to the dreamy, pretty pictures that too often accompany texts like this." — Choice

"Remarkable insight in to the lives of the Ohlone Indians." — San Francisco Chronicle

"A beautiful book, written and illustrated with a genuine sympathy . . . A serious and compelling re-creation." — The Pacific Sun

Two hundred years ago, herds of elk and antelope dotted the hills of the San Francisco–Monterey Bay area. Grizzly bears lumbered down to the creeks to fish for silver salmon and steelhead trout. From vast marshlands geese, ducks, and other birds rose in thick clouds "with a sound like that of a hurricane." This land of "inexpressible fertility," as one early explorer described it, supported one of the densest Indian populations in all of North America.

One of the most ground-breaking and highly-acclaimed titles that Heyday has published, The Ohlone Way describes the culture of the Indian people who inhabited Bay Area prior to the arrival of Europeans. Recently included in the San Francisco Chronicle's Top 100 Western Non-Fiction list, The Ohlone Way has been described by critic Pat Holt as a "mini-classic."

Praise for The Ohlone Way

"[Margolin] has written thoroughly and sensitively of the Pre-Mission Indians in a North American land of plenty. Excellent, well-written." — American Anthropologist

"One of three books that brought me the most joy over the past year." — Alice Walker

"Margolin conveys the texture of daily life, birth, marriage, death, war, the arts, and rituals, and he also discusses the brief history of the Ohlones under the Spanish, Mexican, and American regimes . . . Margolin does not give way to romanticism or political harangues, and the illustrations have a gritty quality that is preferable to the dreamy, pretty pictures that too often accompany texts like this." — Choice

"Remarkable insight in to the lives of the Ohlone Indians." — San Francisco Chronicle

"A beautiful book, written and illustrated with a genuine sympathy . . . A serious and compelling re-creation." — The Pacific Sun

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ohlone Way by Malcolm Margolin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

THE OHLONES AND THEIR LAND

LAND AND ANIMALS

Modern residents would hardly recognize the Bay Area as it was in the days of the Ohlones. Tall, sometimes shoulder-high stands of native bunchgrasses (now almost entirely replaced by the shorter European annuals) covered the vast meadowlands and the tree-dotted savannahs. Marshes that spread out for thousands of acres fringed the shores of the Bay. Thick oak-bay forests and redwood forests covered much of the hills.

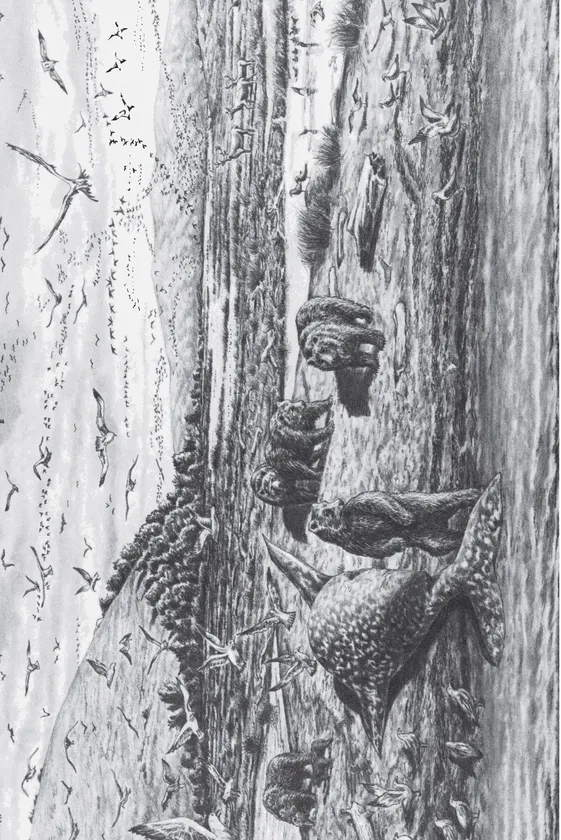

The intermingling of grasslands, savannahs, salt- and freshwater marshes, and forests created wildlife habitats of almost unimaginable richness and variety. The early explorers and adventurers, no matter how well-travelled in other parts of the globe, were invariably struck by the plentiful animal life here. “There is not any country in the world which more abounds in fish and game of every description,” noted the French sea captain la Perouse. Flocks of geese, ducks, and seabirds were so enormous that when alarmed by a rifle shot they were said to rise “in a dense cloud with a noise like that of a hurricane.” Herds of elk—“monsters with tremendous horns,” as one of the early missionaries described them—grazed the meadowlands in such numbers that they were often compared with great herds of cattle. Pronghorn antelopes, in herds of one or two hundred, or even more, dotted the grassy slopes.

Packs of wolves hunted the elk, antelope, deer, rabbits, and other game. Bald eagles and giant condors glided through the air. Mountain lions, bobcats, and coyotes—now seen only rarely—were a common sight. And of course there was the grizzly bear. “He was horrible, fierce, large, and fat,” wrote Father Pedro Font, an early missionary, and a most apt description it was. These enormous bears were everywhere, feeding on berries, lumbering along the beaches, congregating beneath oak trees during the acorn season, and stationed along nearly every stream and creek during the annual runs of salmon and steelhead.

It is impossible to estimate how many thousands of bears might have lived in the Bay Area at the time of the Ohlones. Early Spanish settlers captured them readily for their famous bear-and-bull fights, ranchers shot them by the dozen to protect their herds of cattle and sheep, and the early Californians chose the grizzly as the emblem for their flag and their statehood. The histories of many California townships tell how bears collected in troops around the slaughterhouses and sometimes wandered out onto the main streets of towns to terrorize the inhabitants. To the Ohlones the grizzly bear must have been omnipresent, yet today there is not a single wild grizzly bear left in all of California.

Life in the ocean and in the unspoiled bays of San Francisco and Monterey was likewise plentiful beyond modern conception. There were mussels, clams, oysters, abalones, seabirds, and sea otters in profusion. Sea lions blackened the rocks at the entrance to San Francisco Bay and in Monterey Bay they were so abundant that to one missionary they seemed to cover the entire surface of the water “like a pavement.”

Long, wavering lines of pelicans threaded the air. Clouds of gulls, cormorants, and other shore birds rose, wheeled, and screeched at the approach of a human. Rocky islands like Alcatraz (which means pelican in Spanish) were white from the droppings of great colonies of birds.

In the days before the nineteenth-century whaling fleets, whales were commonly sighted within the bays and along the ocean coast. An early visitor to Monterey Bay wrote: “It is impossible to conceive of the number of whales with which we were surrounded, or their familiarity; they every half minute spouted within half a pistol shot of the ships and made a prodigious stench in the air.” Along the bays and ocean beaches whales were often seen washed up on shore, with grizzly bears in “countless troops”—or in many cases Indians—streaming down the beach to feast on their remains.

Nowadays, especially during the summer months, we consider most of the Bay Area to be a semi-arid country. But from the diaries of the early explorers the picture we get is of a moist, even swampy land. In the days of the Ohlones the water table was much closer to the surface, and indeed the first settlers who dug wells here regularly struck clear, fresh water within a few feet.

Water was virtually everywhere, especially where the land was flat. The explorers suffered far more from mosquitoes, spongy earth, and hard-to-ford rivers than they did from thirst—even in the heat of summer. Places that are now dry were then described as having springs, brooks, ponds—even fairly large lakes. In the days before channelizations, all the major rivers—the Carmel, Salinas, Pajaro, Coyote Creek, and Alameda Creek—as well as many minor streams, spread out each winter and spring to form wide, marshy valleys.

The San Francisco Bay, in the days before landfill, was much larger than it is today. Rivers and streams emptying into it often fanned out into estuaries which supported extensive tule marshes. The low, salty margins of the Bay held vast pickleweed and cordgrass swamps. Cordgrass provided what many biologists now consider to be the richest wildlife habitat in all North America.

Today only Suisun Marsh and a few other smaller areas give a hint of the extraordinary bird and animal life that the fresh- and saltwater swamps of the Bay Area once supported. Ducks were so thick that an early European hunter told how “several were frequently killed with one shot.” Channels crisscrossed the Bayshore swamps—channels so labyrinthian that the Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue got lost in them and longed for a good pilot to help him thread his way through. The channels were alive with beavers and river otters in fresh water, sea otters in salt water. And everywhere there were thousands and thousands of herons, curlews, sandpipers, dowitchers, and other shore birds.

The geese that wintered in the Bay Area were “uncountable,” according to Father Juan Crespi. An English visitor claimed that their numbers “would hardly be credited by anyone who had not seen them covering whole acres of ground, or rising in myriads with a clang that may be heard a considerable distance.”

The environment of the Bay Area has changed drastically in the last 200 years. Some of the birds and animals are no longer to be found here, and many others have vastly diminished in number. Even those that have survived have (surprisingly enough) altered their habits and characters. The animals of today do not behave the same way they did two centuries ago; for when the Europeans first arrived they found, much to their amazement, that the animals of the Bay Area were relatively unafraid of people.

Foxes, which are now very secretive, were virtually underfoot. Mountain lions and bobcats were prominent and visible. Sea otters, which now spend almost their entire lives in the water, were then readily captured on land. The coyote, according to one visitor, was “so daring and dexterous, that it makes no scruple of entering human habitation in the night, and rarely fails to appropriate whatever happens to suit it.”

“Animals seem to have lost their fear and become familiar with man,” noted Captain Beechey. As one reads the old journals and diaries, one finds the same observation repeated by one visitor after another. Quail, said Beechey, were “so tame that they would often not start from a stone directed at them.” Rabbits “can sometimes be caught with the hand,” claimed a Spanish ship captain. Geese, according to another visitor, were “so impudent that they can scarcely be frightened away by firing upon them.”

Likewise, Otto von Kotzebue, an avid hunter, found that “geese, ducks, and snipes were so tame that we might have killed great numbers with our sticks.” When he and his men acquired horses from the missionaries they chased “herds of small stags, so fearless that they suffered us to ride into the midst of them.”

Von Kotzebue delighted in what he called the “superfluity of game.” But one of his hunting expeditions nearly ended in disaster. He had brought with him a crew of Aleutian Eskimos to help hunt sea otters for the fur trade. “They had never seen game in such abundance,” he wrote, “and being passionately fond of the chase they fired away without ceasing.” Then one man made the mistake of hurling a javelin at a pelican. “The rest of the flock took this so ill, that they attacked the murderer and beat him severely with their wings before other hunters could come to his assistance.”

It is obvious from these early reports that in the days of the Ohlones the animal world must have been a far more immediate presence than it is today. But this closeness was not without drawbacks. Grizzly bears, for example, who in our own time have learned to keep their distance from humans, were a serious threat to a people armed only with bows and arrows. During his short stay in California in 1792, Jose Longinos Martinez saw the bodies of two men who had been killed by bears. Father Font also noticed several Indians on both sides of the San Francisco Bay who were “badly scarred by the bites and scratches of these animals.”

Suddenly everything changed. Into this land of plenty, this land of “inexpressible fertility” as Captain la Perouse called it, arrived the European and the rifle. For a few years the hunting was easy—so easy (in the words of Frederick Beechey) “as soon to lessen the desire of pursuit.” But the advantages of the gun were short-lived. Within a few generations some birds and animals had been totally exterminated, while others survived by greatly increasing the distance between themselves and people.

Today we are the heirs of that distance, and we take it entirely for granted that animals are naturally secretive and afraid of our presence. But for the Indians who lived here before us this was simply not the case. Animals and humans inhabited the very same world, and the distance between them was not very great.

The Ohlones depended upon animals for food and skins. As hunters they had an intense interest in animals and an intimate knowledge of their behavior. A large part of a man’s life was spent learning the ways of animals.

But their intimate knowledge of animals did not lead to conquest, nor did their familiarity breed contempt. The Ohlones lived in a world where people were few and animals were many, where the bow and arrow were the height of technology, where a deer who was not approached in the proper manner could easily escape and a bear might conceivably attack—indeed, they lived in a world where the animal kingdom had not yet fallen under the domination of the human race and where (how difficult it is for us to fully grasp the implications of this!) people did not yet see themselves as the undisputed lords of all creation. The Ohlones, like hunting people everywhere, worshipped animal spirits as gods, imitated animal motions in their dances, sought animal powers in their dreams, and even saw themselves as belonging to clans with animals as their ancestors. The powerful, graceful animal life of the Bay Area not only filled their world, but filled their minds as well.

AN OHLONE VILLAGE

Within the rich environment of the Bay Area lived a dense population of Ohlone Indians. As many as thirty or forty permanent villages rimmed the shores of the San Francisco Bay—plus several dozen temporary “camps,” visited for a few weeks each year by inland groups who journeyed to the Bayshore to gather shellfish and other foods. At the turn of this century more than 400 shellmounds, the remains of these villages and camps, could still be found along the shores of the Bay—dramatic indication of a thriving population.

What would life have been like here? What would be happening at one of the larger villages on a typical afternoon, say in mid-April, 1768—one year before the first significant European intrusion into the Bay Area? Let us reconstruct the scene.…

The village is located along the eastern shores of the San Francisco Bay at the mouth of a freshwater creek. An immense, sprawling pile of shells, earth, and ashes elevates the site above the surrounding marshland. On top of this mound stand some fifteen dome-shaped tule houses arranged around a plaza-like clearing. Scattered among them are smaller structures that look like huge baskets on stilts—granaries in which the year’s supply of acorns are stored. Beyond the houses and granaries lies another cleared area that serves as a ball field, although it is not now in use.

It is mid-afternoon of a clear, warm day. In several places throughout the village, steam is rising from underground pit ovens where mussels, clams, rabbit meat, fish, and various roots are being roasted for the evening meal. People are clustered near the doors of the houses. Three men sit together, repairing a fishing net. A group of children are playing an Ohlone version of hide-and-seek: one child hides and all the rest are seekers. Here and there an older person is lying face down on a woven tule mat, napping in the warmth of the afternoon sun.

At the edge of the village a group of women sit together grinding acorns. Holding the mortars between their outstretched legs, they sway back and forth, raising the pestles and letting them fall again. The women are singing together, and the pestles rise and fall in unison. As heavy as the pestles are, they are lifted easily—not so much by muscular effort, but (it seems to the women) by the powerful rhythm of the acorn-grinding songs. The singing of the women and the synchronized thumping of a dozen stone pestles create a familiar background noise—a noise that has been heard by the people of this village every day for hundreds, maybe thousands, of years.

The women are dressed in skirts of tule reeds and deer skin. They are muscular, with rounded healthy features. They wear no shoes or sandals—neither do the men—and their feet are hardened by a lifetime of walking barefoot. Tattoos, mostly lines and dots, decorate their chins, and they are wearing necklaces made of abalone shells, clam-shell beads, olivella shells, and feathers. The necklaces jangle pleasantly as the women pound the acorns. Not far away some toddlers are playing in the dirt with tops and buzzers made out of acorns. Several of the women have babies by their sides, bound tightly into basketry cradles. The cradles are decorated lovingly with beads and shells.

As the women pause in their work, they talk, complain, and laugh among themselves. It is the beginning of spring now, and everyone is yearning to leave the shores of the Bay and head into the hills. The tule houses are soggy after the long winter rains, and everyone is eager to desert them. The spring greens, spring roots, and the long-awaited clover have already appeared in the meadows. The hills have turned a deep green. Flowers are everywhere, and it is getting near that time of year when the young men and women will chase each other over the meadows, throwing flowers at each other in a celebration so joyful that even the older people will join in.

Everyone is waiting for the chief to give the word, to say that it is time to leave the village. All winter the trails have been too muddy for walking long distances, the rivers too wild for fishing, and the meadows too swampy for hunting. Now winter is clearly over. Everyone is craving the taste of mountain greens and the first flower seeds of the spring.

But the chief won’t give the word. A few days before, he had stood in the plaza and given a speech. Anyone was free to go to the hills, he said, but he and his family would stay by the Bayshore for a while longer. Here there were plenty of mussels and clams, the baskets still held acorns, and the fields near the village were full of soaproot, clover, and other greens. In the hills there would be flower seeds, beyond doubt; but there would be very few, and the people would have to spread out far and wide to gather them. They would be separated from each other. A woman might get carried off, a man might get attacked and beheaded. There had been no such problems for several years, true. But this winter many people had fallen ill. Some had even died. Where did the illness come from? Indeed, the villagers had brooded upon the illnesses and deaths for several months now, and many had come to the conclusion that the people to the south were working evil against them.

The women grinding the acorns talk about the speech, and now on this warm spring afternoon they laugh at the chief. He is getting old. He wants to avoid trouble with the neighboring groups, and this is good. But hadn’t two of the young men from the village taken wives from the people to the south? And hadn’t the young men brought the proper gifts to their new families?

Also, the hills do indeed have enough clover, greens, and flower seeds, so that the people will not have to spread out far and wide. Just look at the color! The birds, too, have begun to sing their flower-seed songs in the willows along the creek. It is time to leave. The chief is too cautious, too suspicious. Still, no one leaves for the hills yet. Perhaps in another day or two.

On a warm day like this almost all village activity takes place outdoors, for the tule houses are rather small. Of relatively simple design (they are made by fastening bundles of tule rush onto a framework of bent willow poles), they range in size from six to about twenty feet in diameter. The larger dwellings hold one or sometimes two families—as many as twelve or more people—and each house is crowded with possessions. Blankets of deer skin, bear skin, and woven rabbit skin lie strewn about a central fire pit. Hamper baskets in which seeds, roots, dried meat, and dried fish are stored stand against the smoke-darkened walls. Winnowing, serving, sifting, and cooking baskets (to name only a few), along with several unfinished baskets in various stages of completion are stacked near the entrance way. Tucked into the rafters are bundles of basket-making material, plus deer-skin pouches that contain ornaments and tools: sets of awls, bone scrapers, file stones, obsidian knives, and twist drills for making holes in beads. Many of the houses also contain ducks stuffed with tule (to be used as hunting decoys), piles of fishing nets, fish traps, snares, clay balls ready to be ground into paint, and heaps of abalone shells that have been worked into rough blanks. The abalone shells were received in trade last fall from the people across the Bay, and after being shaped, polished, and pierced they will eventually be traded eastward—for pine nuts, everyone hopes.

While all the houses are similar in construction, they are not identical. One of them, off to the side of the village near the creek, is twice as large as the others and is dug into the earth. It has a tiny door—one would have to crawl on all fours to enter—and it is decorated with a pole from which hang feathers and a long strip of rabbit skin. Its walls are plastered thickly with mud, and smoke is pouring out of a hole in the roof. This is the sweat-house, or temescal, as it was called by the early Spaniards. A number of adolescent boys are lingering around the door, listening to the rhythmic clapping of a split-stick clapper that comes from within. The men are inside, singing and sweating, preparing themselves and their weapons for the next day’s deer hunt. It is here, away from the women...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- Part I - THE OHLONES AND THEIR LAND

- Part II - LIFE IN A SMALL SOCIETY

- Part III - THE WORLD OF THE SPIRIT

- Part IV - MODERN TIMES

- POSTSCRIPT

- AFTERWORD: 2003

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX

- HEYDAY INSTITUTE