- 335 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Thirteen personal accounts of endangered language preservation, plus a how-to guide for parents looking to do the same in their own home.

Throughout the world individuals in the intimacy of their homes innovate, improvise, and struggle daily to pass on endangered languages to their children. Elaina Albers of Northern California holds a tape recorder up to her womb so her baby can hear old songs in Karuk. The Baldwin family of Montana put labels all over their house marked with the Miami words for common objects and activities, to keep the vocabulary present and fresh. In Massachusetts, at the birth of their first daughter, Jesse Little Doe Baird and her husband convince the obstetrician and nurses to remain silent so that the first words their baby hears in this world are Wampanoag.

Thirteen autobiographical accounts of language revitalization, ranging from Irish Gaelic to Mohawk, Kawaiisu to Maori, are brought together by Leanne Hinton, professor emerita of linguistics at UC Berkeley, who for decades has been leading efforts to preserve the rich linguistic heritage of the world. Those seeking to save their language will find unique instruction in these pages; everyone who admires the human spirit will find abundant inspiration.

Languages featured: Anishinaabemowin, Hawaiian, Irish, Karuk, Kawaiisu, Kypriaka, Maori, Miami, Mohawk, Scottish Gaelic, Wampanoag, Warlpiri, Yuchi

"Practical and down to earth, philosophical and spiritual, Bringing Our Languages Home describes the challenges and joys of learning and passing on your language. It gives good detailed advice . . . Fantastic! I hope millions will read it!" —Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, Åbo Akademi University, Finland, emerita

"This rare collection by scholar-activist Leanne Hinton brings forward deeply affecting accounts of families determined to sustain their languages amidst a sea of dominant-language pressures. The stories could only be told by those who have experienced the joys and challenges such an undertaking demands. Drawing lessons from these accounts, Hinton leaves readers with a wealth of language planning strategies. This powerful volume will long serve as a seminal resource for families, scholars, and language planners around the world." —Teresa L. McCarty, George F. Kneller Chair in Education and Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles

Throughout the world individuals in the intimacy of their homes innovate, improvise, and struggle daily to pass on endangered languages to their children. Elaina Albers of Northern California holds a tape recorder up to her womb so her baby can hear old songs in Karuk. The Baldwin family of Montana put labels all over their house marked with the Miami words for common objects and activities, to keep the vocabulary present and fresh. In Massachusetts, at the birth of their first daughter, Jesse Little Doe Baird and her husband convince the obstetrician and nurses to remain silent so that the first words their baby hears in this world are Wampanoag.

Thirteen autobiographical accounts of language revitalization, ranging from Irish Gaelic to Mohawk, Kawaiisu to Maori, are brought together by Leanne Hinton, professor emerita of linguistics at UC Berkeley, who for decades has been leading efforts to preserve the rich linguistic heritage of the world. Those seeking to save their language will find unique instruction in these pages; everyone who admires the human spirit will find abundant inspiration.

Languages featured: Anishinaabemowin, Hawaiian, Irish, Karuk, Kawaiisu, Kypriaka, Maori, Miami, Mohawk, Scottish Gaelic, Wampanoag, Warlpiri, Yuchi

"Practical and down to earth, philosophical and spiritual, Bringing Our Languages Home describes the challenges and joys of learning and passing on your language. It gives good detailed advice . . . Fantastic! I hope millions will read it!" —Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, Åbo Akademi University, Finland, emerita

"This rare collection by scholar-activist Leanne Hinton brings forward deeply affecting accounts of families determined to sustain their languages amidst a sea of dominant-language pressures. The stories could only be told by those who have experienced the joys and challenges such an undertaking demands. Drawing lessons from these accounts, Hinton leaves readers with a wealth of language planning strategies. This powerful volume will long serve as a seminal resource for families, scholars, and language planners around the world." —Teresa L. McCarty, George F. Kneller Chair in Education and Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bringing Our Languages Home by Leanne Hinton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

STARTING FROM ZERO

1: Miami

myaamiaataweenki oowaaha: MIAMI SPOKEN HERE

ceeleelintamaani niišwi iilaataweenkia. myaamia neehi english

(I like having two languages, Miami and English)

(I like having two languages, Miami and English)

—awansaapia, nine years old

Daryl

Aya. kinwalaniihsia weenswiaani. karen weekimaki neehi niiwi piloohsaki eehsakiki. keemaacimwihkwa, ciinkwia, amehkoonsa, neehi awansaapia weenswiciki. myaamiaataweentiaanki wiihsa pipoonwa. ileeši kati neepwaanki ayoolhka.

Greetings! My name is Daryl. I am married to Karen and have four children. Their names are Jessie, Jarrid, Emma, and Elliot. We have been speaking to each other in the Myaamia language for many years, but there is more to learn.

For me personally, language is something that came to me later in life. I was always aware of my Myaamia (Miami) heritage through my father and grandfather, and fortunate to have had a great deal of historical knowledge about previous generations passed on to me. Culture for me was primarily shaped early in life through the intertribal experience, especially powwows. The only language I heard growing up was ancestral names, many of which I did not know the meanings of.

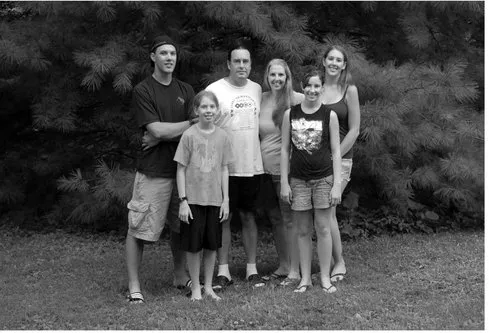

weecikiintiaanki ‘our family’. Photo by Karen Baldwin, courtesy of Myaamia Project Archive

Previous generations of my family were divided by our forced relocation in 1846 from homelands in north central Indiana to a reservation in the unorganized territory, which later became Kansas. In the 1870s our Kansas relatives underwent a second removal to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Some of my ancestors stayed in Kansas and still others remained behind in Indiana and northwest Ohio. As a result of these removals, we as Myaamia people today find ourselves scattered from Indiana, Kansas, and Oklahoma, with families living in almost every state. We are a fragmented community with tribal lands currently consisting of a checkerboard of approximately 1,319 acres primarily located in our jurisdictional area in Ottawa County, in northeastern Oklahoma. The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe with thirty-seven hundred on its citizenship rolls, but there are easily twice that number of individuals throughout the Midwest with Myaamia ancestry.

Linguists refer to our language as “Miami-Illinois.” The Illinois people were a loose confederation of villages located throughout what is now the state of Illinois. Their descendants are today recognized as members of the Peoria Tribe of Oklahoma. The Miami and Illinois groups all spoke slightly different dialects of the same language. All things considered, there are likely ten thousand individuals who can claim ancestry to the Miami-Illinois people.

A desire to pursue my heritage on a deeper level through the language coincided with a key moment in my life. My wife and I had just had our first child and I was entertaining the idea of pursuing higher education, which would bring to an end a successful ten-year career as a carpenter. As a first-generation college student who was married with young children, I knew that college would be very challenging. Determined not to wait any longer to pursue a new path, I quit my career in carpentry, my wife quit her job as a schoolteacher, we sold most of what we owned, and I went back to school. I had no way of knowing the hardships that would come over the next ten years and how deeply my commitment to learning my heritage language would be tested.

During these years of transition, I distinctly remember finding a word list of the Myaamia language buried in my grandfather’s personal papers, which I had recently received. The language was not his, as he was not a speaker, but it was the first time I had seen what I considered my heritage language and I was curious to know if it was still spoken. I asked my father if he knew any speakers and he suggested I travel to both Indiana and Oklahoma to find if any speakers existed in the two Myaamia communities. I followed through with his recommendation and soon learned that the last speakers had passed nearly at the same time I was born, in the early 1960s. There would be no speakers to learn from, and at the time, it wasn’t fully known what documentation was available or if there were any audio recordings.

I remember feeling a sense of loss but also a sense of responsibility when I learned of the status of our language. I became determined to try and learn what I could. At the time I was not familiar with the use of the term “extinct” in referring to our ancestral language. I would soon become familiar with the terms “dead,” “dying,” and “extinct” in reference to languages and would eventually come to challenge these notions as inappropriately applied to well-documented languages that have communities interested in reclamation.

We really didn’t start actively learning the language until my second child came along in 1991. In the beginning, the language consisted of word lists and the desire to name things: household items, birds, animals, and other familiar items common to everyday activities served as our starting point. Word lists taped to walls, counters, and cabinets served as the learning mechanism, along with folded notes in my pockets as I went about my day. My first two children were still very young and so they naturally became part of the learning process, as rudimentary as our effort was. We approached the effort collectively as a family. We were young and uninformed but we were very committed.

During our home efforts of the early 1990s, I remember struggling with pronunciation and understanding the verb system. At that time, a graduate student named David Costa was studying linguistics at Berkeley and was reconstructing the Miami-Illinois language as part of his dissertation research. I remember getting a draft of his dissertation in the mail and, upon opening it, becoming overwhelmed by the linguistic description and jargon. I was just finishing up my undergraduate degree in biology at the University of Montana and decided at that moment that I would pursue graduate studies in linguistics at the same school. My desire to pursue a linguistics degree was not motivated by an interest in being a linguist. Instead, I was interested in obtaining enough training to interpret Costa’s dissertation and use these skills for language reclamation. I was very fortunate to have the guidance of Dr. Anthony Mattina and his wife, Dr. Nancy Mattina, for graduate studies as both understood the complex nature of language revitalization, what I was up against, and what my personal needs were. My best educational experience was my graduate studies in linguistics.

In the early years, my approach to home learning was much more formal than it is now, both in terms of our homeschooling efforts and from my own personal “study” of the language. I learned about the phonology, morphology, and grammar of my language and did tend to teach it based on what I was learning in college. Even on the community level I used to lean heavily towards teaching language from the perspective of grammar, but I have since learned that teaching grammar and teaching to speak are not the same thing. It wouldn’t be until my second two children came along, years later, that we would move towards an immersive approach to teaching. Immersion is much more efficient and effective in passing on the language to young children. However, in the fragmented speaking environment that we have created in our home, due to an evolving fluency, I do think that a certain amount of structured learning has had its benefits. I would say that structured learning is much harder for me to do, primarily because of my own developing fluency level after nineteen years of learning. Sometimes I find myself just wanting to speak and not worry about developing learning aids for the home, but I know learning aids would be useful to my youngest children, who are now ten and thirteen years old.

I would like to turn my attention to some other aspects of home language learning. Learning to think differently is an issue that comes up repeatedly in our home. Just as I was writing this section, my youngest daughter, amehkoonsa, approached me to ask for some of what I was snacking on. I gave her only a very small portion with a smile, knowing that the amount I gave her would not be satisfactory to her. In English she replied, “You know I want more than that,” and my response to her was “taaniši ilweenki” ‘how is that said’ (our typical way to ask for Myaamia to be spoken). She struggled to respond, but not because the vocabulary wasn’t there. She knows from previous instances that the construct of the Myaamia sentence, hence the thought process, is situational and would not exactly match the English. After giving her adequate time to think about it, I supplied, “kiihkeelintamani ayoolhka mee-ciaani” ‘you know I will eat more’, which I did not translate into English, and she repeated without any trouble, knowing exactly what I said. This is a common struggle for our youngest children, less so for the older ones because the translation skills are better. One of the cautions in second-language learning is to understand “how the language thinks,” and we consciously teach that as a skill, always pointing out how Myaamia thinks differently from English. As a side note, I could have translated my daughter’s original English sentence to match the English exactly: kiihkeelintamani neetaweelintamaani ayoolhka iiniini ‘you know I want more than that’, but this would have been anglicizing the language and destroying its own unique thought process.

Staying in the language also has its challenges from a reclamation perspective. As indicated previously, complete fluency is not for this generation. There is no complete and total immersive environment that one can experience in our language. Fluency is an evolving process for us that will come from being immersed in documentation. This is the generation of reintroduction to the language and its unique way of thinking, and rebuilding cultural context for a future fluent environment. From my personal vantage point I see work towards immersion and eventual fluency as a process that will easily take us two to three generations. This is our reality without fluent conversational speakers. With that said, I do believe that communal fluency is achievable in the future, but I likely will not live to see it. Our work in understanding our language, developing cultural fluency, building culturally appropriate teaching models and technologies, building communal educational infrastructure, and developing proven educational pedagogy builds the kind of foundational understanding needed for a future community-wide immersion effort.

Since our language fell dormant in the early to mid-twentieth century, speakers stopped building new vocabulary as they shifted to English. This is why we don’t have words for “refrigerator,” “microwave,” or “airplane,” or not yet at least. Those terms will come with time, but in the interim, I feel strongly that staying with “whole language” utilizing already established vocabulary is important when working with children. In cases where the Myaamia term is clearly known as a non-English word, for instance kinship terms, then it will appear in an English sentence. But depending on the situation, we will either try to speak entirely in Myaamia or entirely in English and not mix the languages to compensate for lack of Myaamia vocabulary. If the Myaamia terms are not available or known, then we simply use English, knowing that with time we will eventually be able to say them in Myaamia.

It’s important to understand that we are not under heavy pressure to “save a language” like so many communities who are witnessing the loss of first-generation speakers. Instead, we are under heavy critique and pressure from our own community to “do this well.” I remember vividly many years ago a well-respected community elder shaking her finger at me and saying, “Don’t screw this up!” I have not forgotten that moment and know that our language is not something to “mess with,” but to handle cautiously with patience and respect. Without speakers there are lots of places for us to “screw up,” but if we allow ourselves adequate time to learn and reflect, I feel confident we can revive our language in a way that honors our past and serves our present needs. We will continue to witness a degree of loss when working with our documentation, and we will continue to see major shifts over time, but I also acknowledge the creative human spirit that has the potential to bring new meaning and purpose to the language we speak today. I am not afraid of that reality.

As for making new terms, we have taken on that challenge when we feel comfortable with the situation at hand. For instance, we now have words such as kiinteelintaakani ‘computer’, aacimwaapiikwi ‘Internet’, and hohowa ‘Santa Claus’. But in cases where language was historically absent, such as for concepts like religion, nature, race, and democracy, we have chosen not to translate those terms for the moment, out of fear that forced translations could affect the way in which the culture handles those ideas. Sometimes there is more to learn from the lack of certain vocabulary than there is from forced translations. Realistically, we know that people in the future will do whatever they want with the language, but for now we want the opportunity to reflect on why our ancestors would not have conceived of these ideas as defined institutional thoughts, and what the implications might be if we “name” and thus “define” them as nominal concepts. I feel this dialogue is essential for language and cultural preservation. If we want to preserve certain aspects of our culture, we must know how our culture differs from others, and our language gives some insight into this important issue. This type of discussion can provide a framework for developing language in culturally appropriate ways for any concept we may want to talk about in the future.

Another important aspect that has emerged with time is the knowledge that our ancestors have always lived directly connected to their food source. Food is at the heart of our culture as ecologically based people. In precontact times all of their sustenance came from the local environment, and food was a product of their ecological knowledge and their skills at growing, harvesting, and intimately knowing what was around them. During the early to mid-nineteenth century our landscape was dramatically altered due to settlement, and our ancestors took up domestic farming, with hogs, cattle, chickens, and a variety of crops, but remained involved in the production of their food.

As a family committed to cultural revitalization as much as we are to language reclamation, we felt this was an important cultural context worth preserving within the home, and we have worked to reconnect to natural processes and participate in the production of our own foods and medicines to some extent. This was a wonderful opportunity for language growth because our linguistic documentation was rich in farm-related vocabulary. Terms for raising animals, butchering, and food preparation are well established, even for animals and plants that were not indigenous to this region. We found that butchering chickens could be done entirely in the language and could even serve as a great opportunity to learn and teach about the internal and external anatomy of the bird.

A farm activity that we became involved in that was absent from our linguistic record was producing milk from dairy goats. The term paapiciihsia ‘goat’ was already established, but there were no milking terms available in the documentation. So we had to create them. We first considered the existing terms noonaakanaapowi ‘milk’, noon-aakani ‘female breast (of human ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- Part I - STARTING FROM ZERO

- Part II - LEARNING FROM THE ELDERS

- Part III - FAMILIES AND COMMUNITIES WORKING TOGETHER

- Part IV - VARIATIONS ON A THEME

- Part V - FAMILY LANGUAGE-LEARNING PROGRAMS

- CONCLUSION: - BRINGING YOUR LANGUAGE INTO YOUR OWN HOME

- CONTRIBUTOR BIOGRAPHIES