eBook - ePub

The Bakersfield Sound

How a Generation of Displaced Okies Revolutionized American Music

- 313 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Bakersfield Sound

How a Generation of Displaced Okies Revolutionized American Music

About this book

An immersive look at the country music sub-genre, from its 1950s origins to its heyday to the twenty-first century.

In California's Central Valley, two thousand miles away from Nashville's country hit machine, the hard edge of the Bakersfield Sound transformed American music during the later half of the twentieth century. Fueled by the steel twang of electric guitars, explosive drumming, and powerfully aching lyrics, the Sound transformed hard times and desperation into chart-toppers. It vaulted displaced Oklahomans like Buck Owens and Merle Haggard to stardom, and even today the Sound's influence on country music is still widely felt.

In this fascinating book, veteran journalist Robert E. Prince traces the Bakersfield Sound's roots from Dust Bowl and World War II migrations through the heyday of Owens, Haggard, and Hee Haw, and into the twenty-first century. Outlaw country demands good storytelling, and Price obliges; to fully understand the Sound and its musicians we dip into honky-tonks, dives, and radio stations playing the songs of sun-parched days spent on oil rigs and in cotton fields, the melodies of hardship and kinship, a soundtrack for dancing and brawling. In other words, The Bakersfield Sound immerses us in the unique cultural convergence that gave rise to a visceral and distinctly California country music.

Praise for The Bakersfield Sound

"A savvy blend of personal anecdotes and broader historical narrative." — Kirkus Reviews

"This book all but reads itself. Price's sense of history, his command of facts, his sense of humor, his sensitivity to class and race, and a love of the music—it's all here." —Greil Marcus

In California's Central Valley, two thousand miles away from Nashville's country hit machine, the hard edge of the Bakersfield Sound transformed American music during the later half of the twentieth century. Fueled by the steel twang of electric guitars, explosive drumming, and powerfully aching lyrics, the Sound transformed hard times and desperation into chart-toppers. It vaulted displaced Oklahomans like Buck Owens and Merle Haggard to stardom, and even today the Sound's influence on country music is still widely felt.

In this fascinating book, veteran journalist Robert E. Prince traces the Bakersfield Sound's roots from Dust Bowl and World War II migrations through the heyday of Owens, Haggard, and Hee Haw, and into the twenty-first century. Outlaw country demands good storytelling, and Price obliges; to fully understand the Sound and its musicians we dip into honky-tonks, dives, and radio stations playing the songs of sun-parched days spent on oil rigs and in cotton fields, the melodies of hardship and kinship, a soundtrack for dancing and brawling. In other words, The Bakersfield Sound immerses us in the unique cultural convergence that gave rise to a visceral and distinctly California country music.

Praise for The Bakersfield Sound

"A savvy blend of personal anecdotes and broader historical narrative." — Kirkus Reviews

"This book all but reads itself. Price's sense of history, his command of facts, his sense of humor, his sensitivity to class and race, and a love of the music—it's all here." —Greil Marcus

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bakersfield Sound by Robert E. Price in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Great Convergence

In 1951, America was still reveling in an exhilarating array of postwar possibilities. The country, vast as it was, seemed smaller than it had a generation before. Its imperfect but resolute goodness had triumphed over ruthless, formidable evil. And that seemed to prove, in most Americans’ minds, that no obstacle on the scale of our ordinary, individual lives could truly be insurmountable. If victory against such odds were possible, it only followed that personal fulfillment, shared among our fellow victors, was inevitable and limitless.

That vitality had produced such colossal bursts of creativity and innovation that people came to expect that everyday life would gradually change for the better—because it had: examples seemed to appear daily. Tupperware, aerosol paint, hairspray, restroom hand dryers, credit cards—all entered the consumer marketplace within five years of Japan’s surrender. Automobiles such as the Nash, the Hudson, the Studebaker, and the Packard, relics of prewar transportation, faded away amid changing wants and expectations. In their place, Americans embraced the sleek 1949 Ford, its distinctive fenders newly integrated into the side of the car body. Chevrolet’s automotive revolution was approaching its final stages of development, with the sinewy, cocksure Corvette nearing readiness for its 1953 unveiling. People have never adapted well to change, generally speaking, but the America of the late 1940s and early 1950s was a vortex of anticipation—blind, buoyant anticipation.1

Into that time and place came what may have been the most drastic departure ever from the accustomed form and function of the musical instrument known as the guitar.

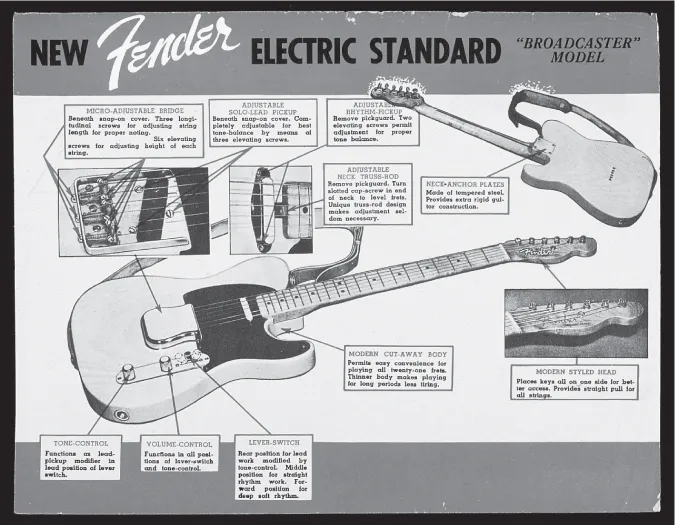

In 1950, after building a succession of prototypes, Clarence “Leo” Fender, a Los Angeles–area guitar maker, unveiled what he called the Fender Telecaster. The solid-body instrument’s name evoked that other great commercial advance in entertainment technology: television, then seeding America’s rooftops with thickets of antennae. The guitar’s design lines conjured forth pulp-fiction versions of interstellar flight, but its function had decidedly Neanderthal overtones. Those modern curves hardly disguised its essential nature: a crude, factory-built, mass-produced object. The guitar’s rough-hewn body, band-sawn from a slab of swamp ash, was attached to a one-piece maple neck that lacked the slightest hint of artistry. No rosewood fingerboard here: the neck was bolted unceremoniously to the body. The tuners were lined up six in a row. Then there was the functional but plain bridge and exposed treble pickup, transferred directly from the steel guitar that had earned Fender his reputation as a maker of worthy electric instruments.

To some musicians, the looks were laughable; compared to the fine Chippendale pieces that Fender’s competitor Gibson was producing, this looked like some sort of primitive weapon. There were no loving applications of the luthier’s customary craft. With its hard edges and simple manners, the Telecaster looked for all the world like the cheaply manufactured guitar it was. But the Telecaster evoked a certain defiance: this was a new type of guitar built in the service of a new, as-yet-unimagined music.

Since the Tele was built from a single, solid hunk of wood, it could be turned up to eleven without howling or cussing back at you—no feedback; pure, sharp tone all the way up to loud. And that bridge pickup cut like barbed wire. Flip a switch, and the Tele could sound like two tomcats brawling in the alley, like steel glancing off steel, like the glassy din of a transistor radio in search of a station. It located and claimed a hitherto uninhabited slice of the audio spectrum all to itself, that high treble range just north of a hillbilly singer’s sinus twang, that pleasure center in the inner ear that craved a spike of sonic brilliance and clarity.2

Guitarists across America, but especially in Southern California, were just starting to discover the wonders of this new instrument when Buck Owens moved to Bakersfield and, within a few weeks of his arrival, made his first investment in Leo Fender’s most famous creation. It was 1951, and Owens’s bandmate, Lewis Talley, had a gently used Telecaster he was willing to part with for thirty dollars. Owens agreed, and American music was never quite the same.

Don Rich performs with Buck Owens sometime before he made the switch from fiddle to guitar—like Owens, his choice would be a Fender Telecaster.

(Photo courtesy of the Buck Owens Private Foundation, Inc.)

The Telecaster gave Owens’s music that distinctively raw edge that set the young guitarist and, more significantly, the musical identity of his adopted city apart from everything. The Bakersfield Sound—as that raucous, outlaw strain of 1960s California country music would eventually come to be known—began as a mixture of diverse musical ingredients, but from the very start, the Telecaster stirred it.

Fender Telecaster magazine advertisement, 1952: unrefined and mass-produced, but capable of cutting through a throbbing bass line and, in a pinch, defending the musician from an onstage assault.

(Image courtesy of the Fender Musical Instrument Corp.)

The story of any period of concentrated creativity is a story of people and relationships. That is true of this story as well, and that electrified plank of swamp ash is one of the protagonists. Owens rarely played anything else. Same for Roy Nichols and James Burton, who played lead guitar, individually and together, for Merle Haggard and the Strangers. Ditto for Don Rich, whose contribution to the Buckaroos was not limited to the high-harmony vocals that meshed so flawlessly with Owens’s. Rich’s seemingly effortless virtuosity on the Telecaster, his creation of a wholly original style wedded to the instrument’s particular qualities, guided the sound of country music— and of rock. Entertainer-historian Marty Stuart once proclaimed on one of his many journeys to the mecca of West Coast country, “They should make a Fender Telecaster the size of the Washington Monument and stick it right in the middle of Bakersfield.”3

Since then, musicians from David Gilmour of Pink Floyd to Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones have embraced the Telecaster. When country stars such as Brad Paisley play the Telecaster, it’s not so much an explicit homage to the Bakersfield Sound as it is a marker of its profound and widespread influence, because the Sound has wound its way so thoroughly into the grain and custom of today’s music.

To be sure, by the time its historical era had crested, the Bakersfield Sound had become more than just one particular musical instrument’s birth story. After all, the origins of the style were broader than country music itself. The stripped-down, bandstand sound associated with Bakersfield, and with Owens in particular, owed as much to rock ’n’ roll as to country, and Owens’s honky-tonk sound was as much Chuck Berry as Eddy Arnold. Certainly, the Beatles thought so: they issued a standing order that all new Buck Owens albums be sent their way immediately upon availability. When they covered “Act Naturally,” it was with Rickenbackers, not Fenders, but that over-the-top treble was there for all to hear.

Even as the Sound was making itself heard as an aesthetic influence in the United Kingdom, its commercial success in the United States had caused a rift in country music’s tradition-bound fabric. If today the Bakersfield Sound comprises an accepted, even canonical style and repertoire and remains a dominant influence in contemporary country music, it was not always so.

In the 1960s, a stylistic ocean separated Nashville from “Nashville West,” the name critics started using to describe Bakersfield in acknowledgement of the city’s chart-topping successes. It was a decade that saw Bakersfield restructure the commercial hierarchies of the country music industry.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Nashville was Bakersfield’s antithesis and simultaneously its fondest aspiration. The two cities behaved like parallel universes that held each other in simultaneous respect and envy, admiration and disdain. The power and centrality of Nashville represented a certain reciprocity to Bakersfield’s small-town belligerence—but it was a belligerence that, at its core, still aspired to win begrudging acknowledgement. Bakersfield had long measured itself against the music capital, even while it occasionally thumbed its nose at Music City’s pretensions and predictability.

Over time, however, Bakersfield was absorbed into Nashville’s monolithic corporate inevitability. Today, Nashville continues to reign supreme, whereas Bakersfield, as an actual country music scene that matters, is a mere remnant of its former self.

Still, once upon a time, a few generations back, the city and its most famous musical style were a single, vibrant living entity.

A Time, a Place, a Vitality

Why do certain places on earth become touchstones of the moment? Sometimes you can’t explain why the cast assembled and started working toward greatness, unbeknownst to them at the time.

—Marty Stuart

Why Bakersfield? Why the 1950s and ’60s? How did so much talent gravitate to one city so far from the capital of country music, to create music of such lasting quality and influence? Good questions. How did Ernest Hemingway end up in Paris in the 1920s, sipping Pernod with Picasso and Gertrude Stein and crafting the short stories that would profoundly redirect American prose?

The historical event that led directly to the creation of a Bakersfield country music culture, that established the southern Central Valley as the ideal soil, topography, and climate for this new music, was, in popular imagination, the Dust Bowl migration of the Great Depression, an epic tale famously chronicled in the pages of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.

Beginning in 1933 and continuing over the next few years, the southern plains and southwestern states—a region comprising the states of Oklahoma, Texas, Colorado, Arkansas, and others— experienced massive dust storms that devastated their farms and transformed the region. Severe drought conditions and farming practices that encouraged erosion of the soil left tens of thousands of family farmers bereft; their livelihoods had literally dried up and blown away with the wind. What ensued was one of the largest mass population shifts in the nation’s history.

The Oklahoma dirt farmers whose professions—and home lives—had been so cruelly obliterated sought refuge in the West, primarily California. But many found their lives largely unchanged from the pre–Dust Bowl days: picking corn and cotton in Oklahoma for poverty wages and picking fruit in the vast farmlands of the Central Valley for poverty wages were different in only one sense. At least in Oklahoma, where many had been self-employed sharecroppers, a sense of independence, however illusory, had been possible. Otherwise, their culture of servitude on land controlled by others had essentially been reconstituted half a continent away.4

Woody Guthrie, the itinerant minstrel from Oklahoma, was one of the first, and certainly the most prominent, to chronicle the migration: his album Dust Bowl Ballads was recorded in 1940 for Victor Records in the months after he fled California. In plainspoken style, with original songs heavily influenced by the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, Guthrie documented the Dust Bowl’s surreal effects on the land, the heartbreak and uncertainty of leaving one’s roots behind and setting out for California, and the oppression and prejudice that the Okies experienced once they arrived.

Not all the musicians who fueled and fostered the Bakersfield Sound were actually the children of “Okies,” as those Dust Bowl refugees were disparagingly called. But many of them were—and every last one of them, poor or not, understood that sort of life and that desperation. Owens, born in Sherman, Texas, in 1929, was the son of sharecroppers whose family’s 1937 exodus to California from the Red River region was delayed for more than a decade when their trailer hitch broke in Phoenix. Bill Woods, who led the band at the Blackboard, a legendary Bakersfield honky-tonk, was born in Denison, Texas, in 1924, the son of a Pentecostal minister who worked the desolate oil-field tent camps of east Texas. Merle Haggard, born in 1937 and raised, for part of his youth, in a converted boxcar in Oildale—then an Okie shantytown just north of the Kern River from Bakersfield—was the son of a Santa Fe Railroad worker from Checotah, Oklahoma, who died when Merle was nine. Dozens of Bakersfield musicians like these men first glimpsed their life’s calling by the light of a campfire or a front-porch lantern as the sweat from a harsh day in the fields dried on their backs.

They could have thrown their guitars over their shoulders and gone elsewhere to make a living at music—after all, freight trains were free, if you knew how to hop aboard without getting caught or run over. But the fact was, the audiences most likely to appreciate their songs about cotton fields and empty cupboards were right there—in Kern County, at the southern end of California’s great San Joaquin Valley. They too were displaced people who hadn’t quite found a new home in the world, stuck in between what they once had been and what they dared hope to become.

“Those Bakersfield musicians had a story to tell,” Herb Pedersen, singer-songwriter and guitarist for the Desert Rose Band, once explained to me. “That’s how they would write the songs. Working, being turned away—that was their experience. They might have made it out here to California, to find work, with little or nothing.” And that shared experience—give a listen to the ache in Haggard’s “Mama’s Hungry Eyes”—clicked with the crowds in the dance halls and honky-tonks of Bakersfield.

“The music was simple but powerful, played by simple-living people who had to leave their farms to come west,” singer Tommy Collins, an Oklahoma native who wrote his first hit songs after moving to Bakersfield in 1951, told me. “There’s quite a history to the camaraderie that developed between those Dust Bowl people. They weren’t apt to go for fancy music.”

Not that Bakersfield performers had a monopoly on being poor. Many of the past century’s country musicians, from all corners of North America, seem to have risen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface to the Heyday Edition

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Great Convergence

- Chapter 2: Toward Eden

- Chapter 3: Honky-Tonk Paradise

- Chapter 4: Vegas of the Valley

- Chapter 5: What’s on TV?

- Chapter 6: Buck Owens

- Chapter 7: Merle Haggard

- Chapter 8: The Two Defining Songs

- Chapter 9: The A & R Man

- Chapter 10: The Mentor, the Muse, and the Protégé

- Chapter 11: The Next Wave

- Afterword

- Appendixe A: The Founders

- Appendixe B: And a Cast of Thousands

- Appendixe C: The Landmarks

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography