eBook - ePub

Dividing Hispaniola

The Dominican Republic's Border Campaign against Haiti, 1930-1961

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The island of Hispaniola is split by a border that divides the Dominican Republic and Haiti. This border has been historically contested and largely porous. Dividing Hispaniola is a study of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo's scheme, during the mid-twentieth century, to create and reinforce a buffer zone on this border through the establishment of state institutions and an ideological campaign against what was considered an encroaching black, inferior, and bellicose Haitian state. The success of this program relied on convincing Dominicans that regardless of their actual color, whiteness was synonymous with Dominican cultural identity.

Paulino examines the campaign against Haiti as the construct of a fractured urban intellectual minority, bolstered by international politics and U.S. imperialism. This minority included a diverse set of individuals and institutions that employed anti-Haitian rhetoric for their own benefit (i.e., sugar manufacturers and border officials.) Yet, in reality, these same actors had no interest in establishing an impermeable border.

Paulino further demonstrates that Dominican attitudes of admiration and solidarity toward Haitians as well as extensive intermixture around the border region were commonplace. In sum his study argues against the notion that anti-Haitianism was part of a persistent and innate Dominican ethos.

Paulino examines the campaign against Haiti as the construct of a fractured urban intellectual minority, bolstered by international politics and U.S. imperialism. This minority included a diverse set of individuals and institutions that employed anti-Haitian rhetoric for their own benefit (i.e., sugar manufacturers and border officials.) Yet, in reality, these same actors had no interest in establishing an impermeable border.

Paulino further demonstrates that Dominican attitudes of admiration and solidarity toward Haitians as well as extensive intermixture around the border region were commonplace. In sum his study argues against the notion that anti-Haitianism was part of a persistent and innate Dominican ethos.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dividing Hispaniola by Edward Paulino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

“THE BARBARIANS WHO THREATEN THIS PART OF THE WORLD”

Protecting the Unenforceable

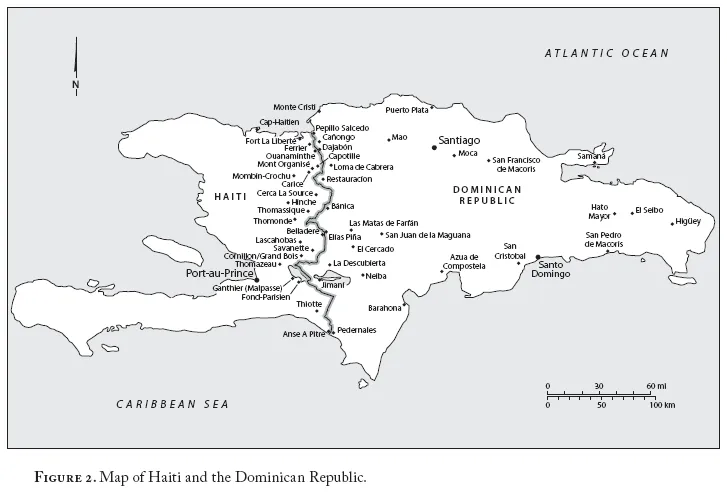

Borders have always shaped the history of Hispaniola, but they are not always man-made. Hispaniola lies on top of the Caribbean Plate, which presses against the North American Plate. The contact and tension between these tectonic plates resulted in land being pushed to the surface, creating the islands of the Caribbean. The prevailing theory among scholars of Caribbean history is that “70–50 million years ago” volcanic activity produced by the pressure between the North American and Caribbean plates created the Greater and Lesser Antilles.1 Pressures between these plates created two major tectonic fault lines surrounding Hispaniola, over the past five hundred years have produced a major earthquake every fifty years. These two borders arguably are the most relevant features in all physical life on the island. Five mountain ranges comprise the next-oldest borders: (1) Sierra Septentrional; in Haiti, Plaine du Nord; (2) Sierra Central; Massif du Nord; (3) Sierra de Neiba; Montagnes Noires, Chaîne des Matheux, and Montagnes du Trou d’Eau; (4) Sierra de Bahoruco; Massif de la Sella, and Massif de la Hotte; and (5) Cordillera Oriental (the only mountain range that does not span into Haiti).2 Then there are the original man-made borders.

In 1492 when Columbus arrived on Hispaniola the island was controlled by five regional chieftaincies.3 These kacicazgos were comprised of villages “with over one-hundred houses and populations numbering from one to three thousand.”4 Territoriality in pre-Columbian Hispaniola did exist, but these regional chieftaincies do not appear to have been geographically delineated. Hispaniola’s intra-island trade was controlled by chieftains (caciques) long before the creation of the vertical boundary that marked the colonial and modern periods.

The parameters between regions were manifested in trade networks and sometimes cemented by marriages. Cacique Behecchío, who controlled much of today’s Haiti, married off a sister to the cacique Caonabo, who controlled what today is the southern part of the Dominican Republic.5 Three of the five geographical chieftaincies overlapped the geographic areas that would become the modern-day Dominican–Haitian border. The geographical regions that exist today are indigenous remnants of those regions. The frontier and subsequently the political boundary on Hispaniola that created Haiti and the Dominican Republic emerged out of the colonial struggle between France and Spain to establish imperial control. The fluid “border region” consisted of a changing collection of local geographies, with key border crossings in the north and south playing important roles in the island’s development. These multiple boundaries shifted among various groups in power in Santo Domingo, eventually leading to today’s 360-kilometer borderline dividing the island.6

THE FRONTIER AS A RACIAL AND ECONOMIC THREAT

The trajectory of colonial settlement and geography are important in understanding the origins of the boundary that produced two distinct European colonies. By settling on eastern Hispaniola and establishing Santo Domingo as its major platform for subsequent colonial projects in the Americas, Spanish colonial power strengthened in the eastern part of the island. This ushered in the enslavement of the indigenous population, whose demographic collapse led to the importation of African slaves.

An early census in 1508 recorded an Indian population of 60,000. The numbers declined precipitously from disease and harsh working conditions in the gold mines.7 In 1510, there were 40,000; in 1511, 33,523; in 1514, 26,334; and in 1519, 3,000.8 After 1520, as the supply of Indian labor in the gold mines became insufficient, the Spanish shifted their operations to sugar. Bartolomé de las Casas, who had suggested the importation of enslaved Africans to work in the ingenios (sugar mills) in 1520, soon saw their numbers rival the Spanish population.

A Royal Dispatch of 1523 from Pamplona, Spain, fearing the growing number of blacks and specifically marronage (runaway slaves and runaway slave communities), ordered colonial officials to severely punish runaway slaves, and required that because there are “more blacks than Spaniards on this island, a good means to avoid uprisings would be that only one in four men assigned to each Spaniard be black.”9 According to Hugo Tolentino Dipp, the Spanish colonial chronicler Antonio Herrera y Tordesillas echoed the Crown’s concern: “So many blacks had passed through here [Santo Domingo] that although profit from sugar was moving along very well with them and with much benefit, there were so many that it was scandalous in Hispaniola and San Juan [Puerto Rico].”10

Fernando Oviedo, a colonist, wrote that “due to those sugar mills there are now so many [black people] that it seems this land is a copy of Ethiopia.”11 The African slave population surpassed the Spanish/white population, which dropped from 12,000 in 1502 to 5,000 in 1546.12 Spanish (whites) ceased to be the racial majority and eventually the country’s racial minority, until their numbers “miraculously” increased in the twentieth century under the government of Rafael Trujillo. By the 1600s individual censuses confirmed this; in 1679, out of nine towns surveyed, Spaniards were in the minority.13 This demographic reality informed Spaniards’ fear of losing power in eastern Hispaniola. In an August 27, 1683, letter to King Charles II, the bishop of Santo Domingo, Fernando de Navarrete, wrote: “Because whites are so few . . . they (mulattos) are so arrogant” and that, recognizing this shortage, “in a few years the government will be in their hands.”14

Exploitation and widespread disease forced many indigenous peoples, and later Africans, to flee their enslavement and escape to the unsettled regions beyond the control of Spanish authorities. These regions were usually mountainous and far from colonial centers like Santo Domingo. One such region was to become the frontier.15 For the indigenous and, later, African slaves freedom meant escaping colonial communities where Spanish control was weak. In the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries some of these runaway communities (palenques) appeared in an emerging frontier that represented a long-standing challenge for governments in claiming sovereignty over this region.

Marronage was by no means unique to Hispaniola. It shared certain traits with its counterparts across the hemisphere. In reviewing Latin American marronage in the region Richard Price describes: (1) an almost inaccessible geography; (2) use of guerilla warfare by runaway slaves; (3) slaves at a numerical disadvantage compared to colonial forces; and (3) a dependency on nearby plantation societies but also collusion and interdependency with colonial centers.16 All these markers of marronage existed in Hispaniola.

Since the early days of European colonization the space beyond colonial rule was seen as a racial and subversive threat by the central authorities. For years the famous Taino chief Enriquillo eluded Spanish authorities by hiding in the Hoyo de Pelempito, the densely forested Baoruco mountain valley range in what is today the Dominican southwestern border region.17 In the mid-1500s Spanish colonial authorities were confronting a black runaway population on Hispaniola estimated at between 2,000 and 3,000.18 They set out to destroy these communities, many located on the colony’s periphery. Under the leadership of the soldier Alonso de Cerrato a ruthless campaign of “pacification” began. Most of the black cimarrón leadership was killed.19 However, the campaign failed to eradicate the black and Indian runaway ex-slave communities in this sparsely populated region. Long after Enriquillo, the mountainous southwestern region continued to be a site of refuge for runaway slaves for over three hundred years. A major reason was the rise of the French colony Saint Domingue in western Hispaniola. Its dependence on sugar and slavery forced many cimarrónes to flee eastward tcoward the Bahoruco Mountains and establish Le Maniel, the island’s most significant Maroon community.20

In compiling letters from the Real Audiencia in Santo Domingo to Seville, Genaro Rodríguez Morel found that runaway slaves targeted ingenios (sugar mills) near the frontier. Writing in 1546, a lawyer named Cerrato describes how cimarrónes from La Vega traveled to San Juan de la Maguana and helped liberate all the slaves from two ingenios with two hundred slaves.21 The slaves returned to burn down the mills. Colonial authorities reacted swiftly. One hundred were recaptured and killed, many “choked, their feet burned or shipped off the island.”22

The sixteenth century saw the rise of the French presence on the western end of Hispaniola. The French settled first on the island of Tortuga off the northern coast of Haiti and gradually occupied the western parts of Hispaniola. An economy of contraband complete with pirates emerged in the west that made it more profitable for Spanish colonists to trade in an emerging frontier with French, English, Dutch, and Portuguese than to purchase imported goods directly from the Crown in Spain.23 According to one Dominican scholar who became a staunch ideological supporter of the Trujillo regime, Manuel A. Peña Batlle, “The foreigners paid better than the Spaniards, bought much more, diversified the exchange, and provided the inhabitants on many occasions with many more things than what was sent from Spain.”24 The contraband trade also thrived due in part to a weak Spanish presence in its western frontier.25

By the 1600s the contraband trade and the semiautonomous and multiracial communities of the Spanish colony’s western periphery represented a complicated challenge—an alternative social and racial hierarchy to Santo Domingo authorities. Indeed, the racial status quo of Santo Domingo seemed unenforceable on its periphery. A vibrant culture emerged from a mix of runaway African slaves, indigenous peoples, and Spanish and French settlers, according to anthropologist Lynn Guitar.26

Spanish colonial authorities, unable to conquer their European rivals in mercantilistic struggles of empire over territory in the Caribbean archipelago, led the Spanish Crown to import families from the Canary Islands to boost the population of eastern Hispaniola, especially in frontier towns such as Bánica, as buffer zones against French settlers and runaway slave communities in the late seventeenth century. As Manuel Vicente Hernández González writes: “The jurisdictional conflict between the military authorities and the local mayors along the border represented a constant throughout the [eighteenth] century. It was difficult for these military authorities to control the livestock trade through these localities, which saw in it not only their principal business but their survival.”27 For historian Frank Moya Pons, Santo Domingo authorities saw the Canarios “as a living frontier”28 and continued to import Europeans to settle the region as a counterweight to French colonists gradually expanding east.

Faced with the inability to oust the French from western Hispaniola and unable to control a multiracial community entrenched in an increasingly lucrative contraband trade on its frontier, Spanish colonial authorities resorted to a policy of relocating the population near the city of Santo Domingo. This policy, called las devastaciones (devastations) or depoblaciones, (depopulating) according to Genaro Rodríguez Morel, was arguably “the most traumatic event that the island’s population suffered and particularly the inhabitants of those affected zones.”29 The goal was to counter the contraband trade that robbed the Spanish Crown of revenue.

A 1603 letter from the Crown to Hispaniola Governor Osorio suggested that forced removal of border residents would end the contraband trade and reroute it through Santo Domingo.30 But the political geography of the frontier, by that time a semiautonomous refuge more than one hundred years old, encouraged many colonial residents in the region to refuse relocation orders.31 Protests against this policy from Santo Domingo escalated into a popular rebellion. The population (primarily black and mulatto) in frontier communities fled to the mountains.32 This was one of the first of many attempts by colonial Spanish authorities in Santo Domingo to wrest control of a region considered a tangible economic and racial threat.

The failed relocation project opened the door to permanent French settlement in the northwestern half of Hispaniola (precisely what the Spanish authorities in Santo Domingo had feared) and the frontier continued to be the site of conflict between colonial Spain and France.33 At the same time, although the Spanish colonists would lose control of western Hispaniola, they would increasingly come to see their western neighbors’ success in the sugar industry as a model for progress, an example to be emulated. The classic French-centric travel account by the Martinican M. L. Moreau de Saint-Méry, who visited the island in the late eighteenth century, captures this historical moment when western Hispaniola flourished economically, becoming the most prosperous part of the island and indeed the cultural capital of the Caribbean.

Saint-Méry found what many people in the Atlantic World already knew: French Saint Domingue occupied a much more advanced economic and cultural position than its Caribbean counterparts, including Spanish Santo Domingo. In western Hispaniola there existed an “active industry and a joy that extends to luxury items,” while in the east “everything shows sterility.”34 Its colonial society would reach nearly 500,000 persons at the end of the eighteenth century (a majority slaves). Citing a census from 1737, Saint-Méry suggests that Santo Domingo was underpopulated and “demonstrates clearly that the total population of Spanish Hispaniola reached no more than six thousand.”35

By the 1700s the colonial sugar plantation system had become lucrative in Saint Domingue, producing a quarter of the entire world’s sugar production. The industry depended on the brutal and inhumane system of bondage. On the eve of the Haitian Revolution in 1791, “a half million” slaves comprised the majority of the population in the French colony.36 By the time of Saint-Méry’s visit to the island, Santo Domingo’s economic importance to the crown had diminished substantially. Santo Domingo did not view its neighbor with hostility, confirming the notion that government-driven policies against Haiti were historically intermittent and informed by particular historical moments.

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries authorities in Santo Domingo considered their neighbor Saint Domingue’s reliance on slavery as a model for progress and economic development, even espousing the importation of African slaves. They were still concerned about the lack of racial hierarchy on their side of the island. This helps explain one of the most important distinctions in how the race issue evolved in eastern Hispaniola: the emergence of a large independent nonwhite peasantry in the absence of a plantation economy. The Spanish encounter with larger indigenous societies such as the Aztecs and Incas ensu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. “The Barbarians Who Threaten This Part of the World”: Protecting the Unenforceable

- Chapter 2. “Making Crosses on His Chest”: U.S. Occupation Confronts a Border Insurgency

- Chapter 3. “A Systematic Campaign of Extermination”: Racial Agenda on the Border

- Chapter 4. “Demands of Civilization”: Changing Identity by Remapping and Renaming

- Chapter 5. “Silent Invasions”: Anti-Haitian Propaganda

- Chapter 6. “Instructed to Register as White or Mulatto”: White Numerical Ascendency

- Epilogue: “Return to the Source”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index